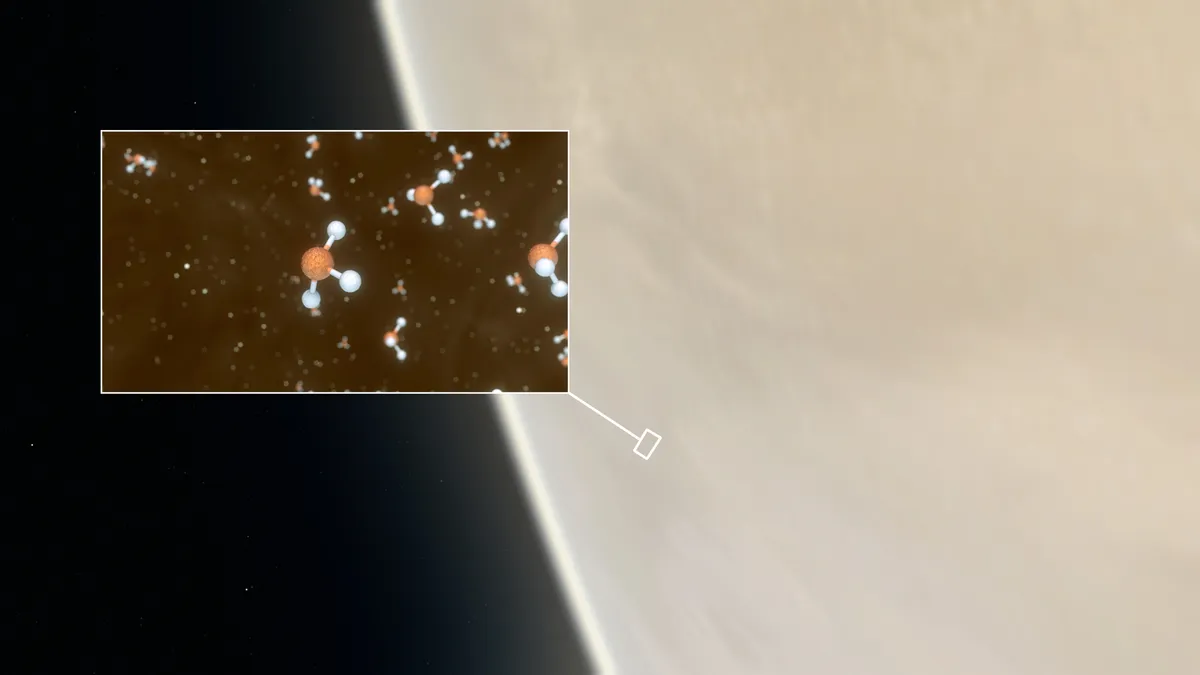

In September 2020, researchers led by Jane Greaves at Cardiff University published spectra collected by radio telescopes that indicated the presence of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus.

The debate this announcement subsequently triggered has been almost as heated as the Venusian climate.

Experts have already published papers calling into question whether the gas is definitely there, as well as questioning what geological processes or atmospheric chemistry could have produced the gas, or whether it could feasibly be the signature of ultra-hardy Venusian life forms.

Read more from Lewis Dartnell:

- Winds on Mars: understanding the Red Planet's atmosphere

- Could an exoplanet's atmosphere indicate the presence of life?

- Is it possible to make a map of an exoplanet?

I was particularly taken by the response from Rakesh Mogul at Cal Poly Pomona, California, and his colleagues, who have gone back to reanalyse 40 year-old data.

In December 1978 the Pioneer Venus multiprobe mission deployed four probes into the Venusian atmosphere.

The largest of these had an onboard mass spectrometer that measured the concentrations of different gases as it parachuted towards the surface.

Phosphorus compounds were not initially reported from these spectra, but Mogul has reanalysed this heritage data to see if there may have been signs of phosphine overlooked in the late 1970s.

Mogul stresses that they can only draw tentative conclusions from these mass spectra, but they are certainly tantalising.

There is a signal at 33.992 amu (atomic mass units; phosphorus is ~30.9, and hydrogen ~1), which matches what you would expect from phosphine (PH3; 33.997).However, hydrogen sulphide (H2S) is also very close, at 33.987.

Mogul and his team believe they can rule out a significant abundance of hydrogen sulphide though because there is no detection of isotope variants. If they’re right, it means that phosphine may have been lying unnoticed in these Pioneer spectra for four decades.

Mogul and his colleagues submitted their analysis to the Nature, Matters Arising journal, which is set up to allow fast turn-around commentary or responses to recent publications.

As such, this is one of the shortest papers I’ve reported on - just three pages without the bibliography - but I think it illustrates how scientific knowledge advances in jerky steps.

One research group analyses their results as thoroughly and dutifully as they can and then submits their report to a journal. This data and their interpretation are then scrutinised by peer reviewers, before being published for the scientific community and a press release sent to journalists.

Then, if it’s particularly significant or controversial, other scientists around the world will race to attempt to replicate or refute the findings using alternative instruments or datasets.

And this is what we are seeing playing out with the Venus phosphine announcement.

Mogul and his colleagues have looked back over heritage data from the early Pioneer probes, and without a doubt astronomers will be scrambling to get observation time on ALMA or other radio telescopes to attempt to confirm the phosphine detection.

There has also been a surge in interest to return to Venus with descent probes to investigate the cloud chemistry close-up.

The DAVINCI probe, currently shortlisted for construction by NASA, is one particularly exciting prospect, but we’ll have to wait until summer 2021 to see if it’s selected.

Prof Lewis Dartnellis an astrobiologist at the University of Westminster.

Lewis was reading Is Phosphine in the Mass Spectra from Venus’ Clouds? by Rakesh Mogul et al. Read it online at arxiv.org.

This article originally appeared in the December 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.