Known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), the black hole at the centre of our Galaxy lies more than 26,000 lightyears from Earth, and is around four million times the mass of the Sun.

Sgr A* was discovered by astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert L. Brown, who revealed in a 1974 science paper that they had discovered a bright radio source at the centre of the Milky Way.

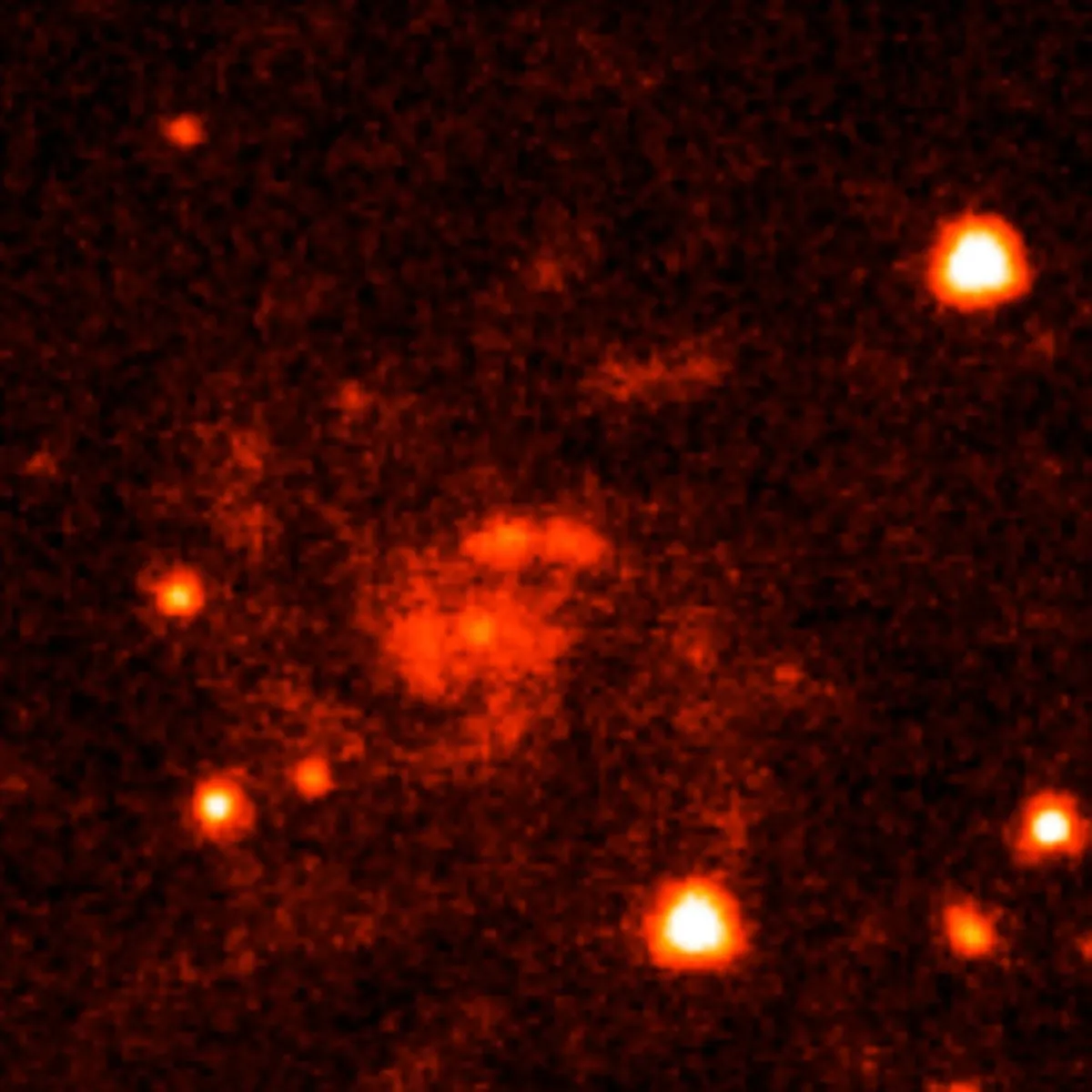

The hot gas and dust around the black hole means it glows brightly at radio, X-ray and gamma ray wavelengths.

Read our answers to some of the biggest questions about black holes.

Astronomers have known for decades that over the timescale of a day the emissions will suddenly flare, increasing in brightness by ten to a hundred times, but weren’t sure how this flaring behaved over longer time spans.

Recently, astronomers have discovered that Sagittarius A* erupts unpredictably and chaotically, using over 15 years of data on the black hole.

Alexis Andrés is a postgraduate student from the University of Amsterdam. He looked at data taken by the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, a telescope that has been looking for gamma ray bursts since 2006.

"The long dataset of the Swift Observatory did not just happen by accident," says Nathalie Degenaar, who requested the specific measurements from Swift when she was a PhD student and became Andrés’s supervisor at the University of Amsterdam.

"Since then, I’ve been applying for more observing time regularly. It’s a very special observing programme that allows us to conduct a lot of research."

This data showed that Sgr A* had a high rate of flares from 2006 to 2008, which then dropped off before rising once again in 2012.

"How the flares occur remains unclear," says Jakob van den Eijnden from the University of Oxford.

"It was previously thought that more flares follow after gaseous clouds or stars pass by the black hole, but there is no evidence for that yet.

"And we cannot yet confirm the hypothesis that the magnetic properties of the surrounding gas play a role either."

The team hope to uncover more about the flare’s changing rate by monitoring Sgr A* using Swift over the next few years.

This should reveal whether a passing cloud or an as yet unknown phenomenon is causing this fitful behaviour at our Galaxy’s heart.

This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.