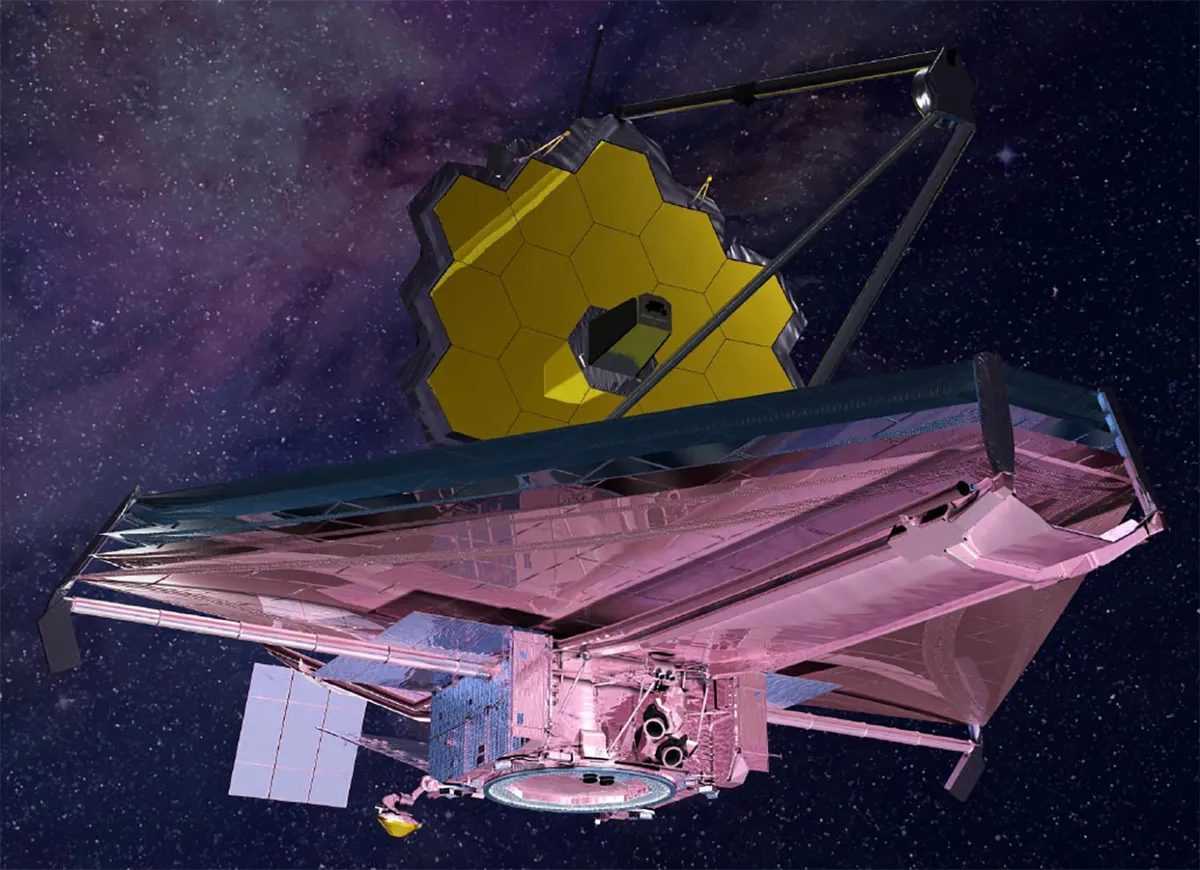

The James Webb Space Telescope is revolutionising our view of the Universe, capturing breathtaking images of nebulae, galaxies, stars and distant exoplanets.

It's peering deep into space, effectively looking back in time to just after the Big Bang, showing us well-formed galaxies that shouldn't exist so early in cosmic history.

But despite its extraordinary power, there’s something Webb can’t do, and that's look at three of the inner planets in our own Solar System: Mercury, Venus and Earth.

That might seem counterintuitive. After all, shouldn’t a telescope that can see billions of lightyears away be able to handle a few nearby planets?

The reason lies in where Webb is, how it operates and the extreme sensitivity of its instruments.

Webb's orbit

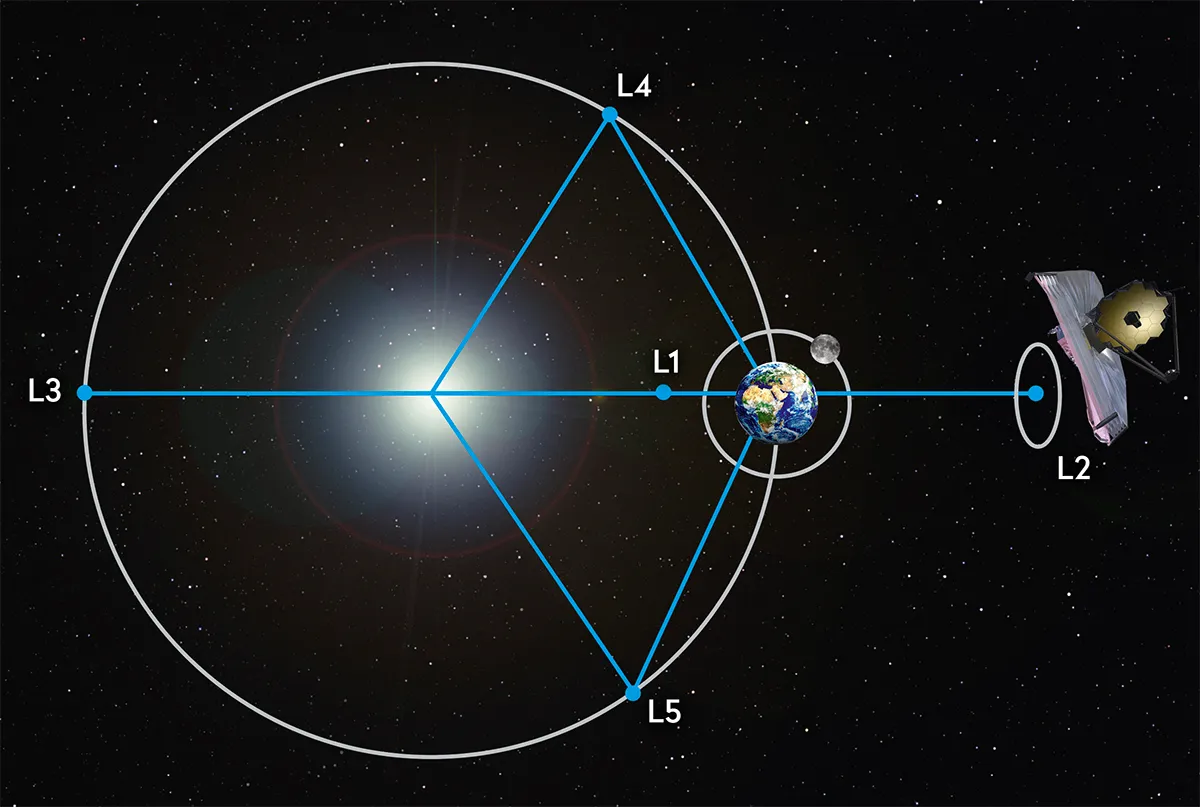

While the Hubble Space Telescope orbits Earth, Webb, on the other hand, orbits the Sun.

Specifically, it orbits a point in space called the second Lagrange point, or L2, about 1.5 million kilometres (almost a million miles) from Earth, on the opposite side of Earth from the Sun.

At Lagrange point 2, the gravitational forces of the Earth and Sun balance out, allowing the telescope to stay in a stable position and thereby minimising fuel use.

From this vantage point, Webb keeps the Earth and Sun in nearly the same direction in the sky at all times.

Why Webb orbits at L2

The James Webb Space Telescope orbits at L2 to help it carry out its primary mission, and that's observing faint infrared light from the early Universe and distant objects in deep space.

Infrared light can be read as heat by its instruments, so Webb needs to be shielded from bright, hot sources.

At L2, it's facing towards the deep cosmos and away from Earth and the Sun.

Webb has a tennis court-sized sunshield to protect its sensitive mirrors and instruments from the Sun, Earth and the Moon, but also from the heat radiated by the spacecraft itself.

Webb's instruments operate at about –225°C (—370*F), so keeping it cool is a necessity.

Why Earth, Venus and Mercury are out of the picture

With that in mind, it's easy to see why Webb can't observe Earth, Venus or Mercury.

Webb is operating beyond Earth's orbit, so if it attempted to look at Earth, Venus or Mercury, it would have to look back in the direction of the Sun, which would defeat all the planning and engineering that's gone in to keeping it cool.

It would expose Webb's instruments to intense heat and sunlight; potentially catastrophic for a telescope engineered to be kept cold.

What if Webb did look towards the Sun?

If Webb did turn and look at Earth, Venus, or Mercury, its sunshield would no longer protect it.

The infrared instruments – intended to be kept cool – would warm up, effectively blinding them.

It's also likely that the instruments could be damaged, ending the mission entirely.

Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope, whose orbit around Earth meant astronauts could service, fix and upgrade it, Webb has been designed not to be serviced, as it's so far away.

What Webb can see in the Solar System

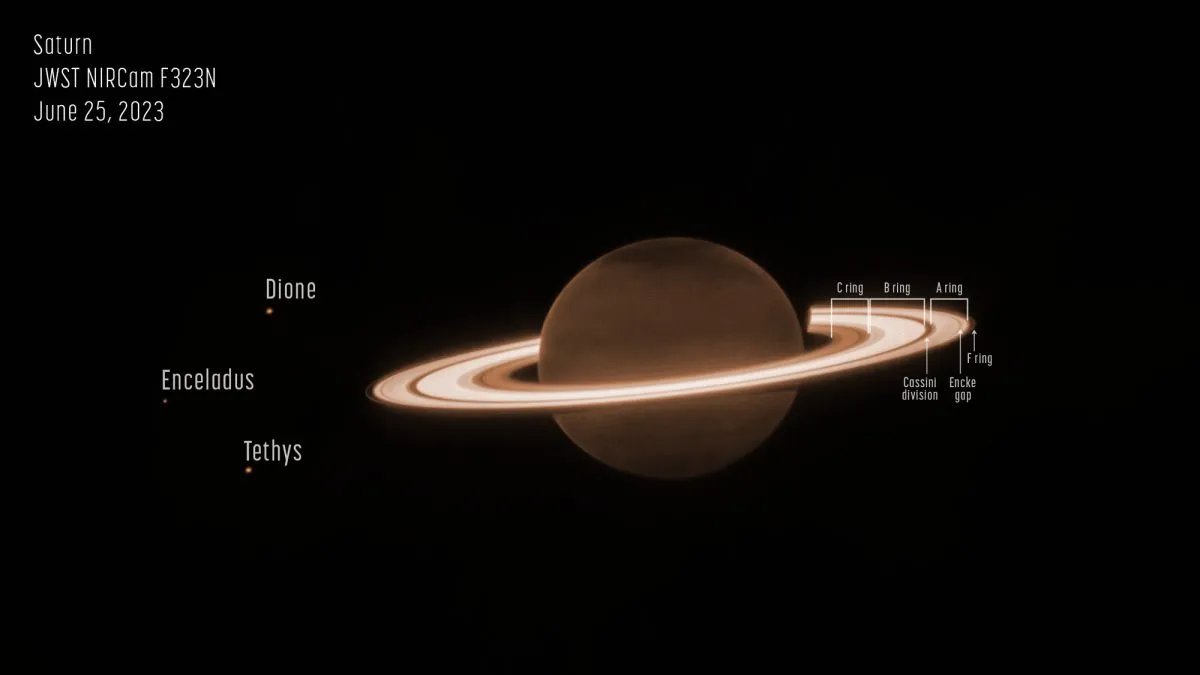

The James Webb Space Telescope can still observe much of the Solar System, beyond Earth's orbit.

It's already studied Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and several of their moons.

It can also observe asteroids and Kuiper Belt objects like Pluto. These are all located far enough from the Sun’s glare for JWST to safely observe them.

So while Webb won’t be giving us a new view of Mercury’s cratered surface or a close-up of Earth from afar, its design is a careful balance of engineering and science.

Webb's position at L2 and its avoidance of sunlight aren’t flaws. They’re essential to unlocking the secrets of the distant Universe.