He was the most recognisable scientist since Albert Einstein, but what made Stephen Hawking such an enduring figure and what did he discover about our Universe?

More on great scientific minds

Early life

Stephen William Hawking was born on 8 January 1942 in Oxford. Yet it was that other bastion of English academia – Cambridge – where he would make his name.

In 1979, he became the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, a hallowed post once held by Isaac Newton.

Much earlier, in 1966, Hawking completed his PhD thesis at Cambridge titled ‘Properties of Expanding Universes’.

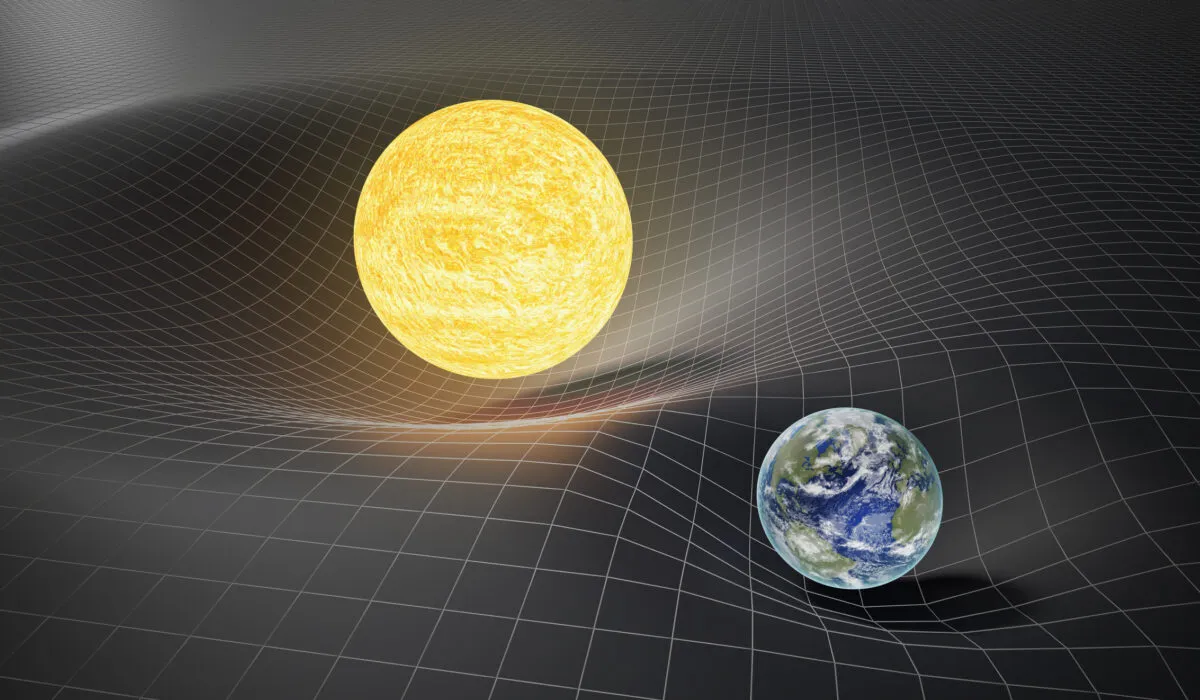

Newton may have described gravity as an invisible, attractive force between two massive objects, but that idea had been thrown out thanks to Albert Einstein.

According to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, massive objects warp the fabric of the Universe around them and other objects can get caught in this distortion.

The apparent attractive force is merely an illusion caused by this.

Hawking’s PhD thesis took these ideas and applied them to the very beginning of the Universe.

The fabric of the Universe that’s warped by massive objects is known as spacetime.

Hawking’s thesis contained a bombshell statement, one that lit a fire under his fledging career and set him on a path towards international stardom.

Spacetime, he said, could begin and end at a singularity. What’s more, he could prove it.

Stephen Hawking, singularities and black holes

A singularity is an infinitely small speck. A point with no size.

To prove that such a thing could exist, Stephen Hawking envisaged a Universe with no singularities.

He showed that this led to a fundamental contradiction: two opposing ideas about the shape of our Universe would simultaneously be true.

As this was impossible, singularities had to exist.

It was a killer breakthrough. In the 1960s, astronomers were still fiercely debating whether the Universe had an origin or whether it had been around forever.

Today, most astronomers are happy to concede that the Universe did start with a singularity.

Although it usually goes by a far more recognisable name: the Big Bang.

The Big Bang isn’t the only place in the Universe where singularities crop up.

They also appear at the centre of black holes, enigmatic objects forged when the most massive stars die.

As the core of the star collapses, spacetime is squashed down into a singularity.

Stephen Hawking spent a lot of time thinking about black holes, particularly an idea now known as Hawking radiation.

Hawking radiation

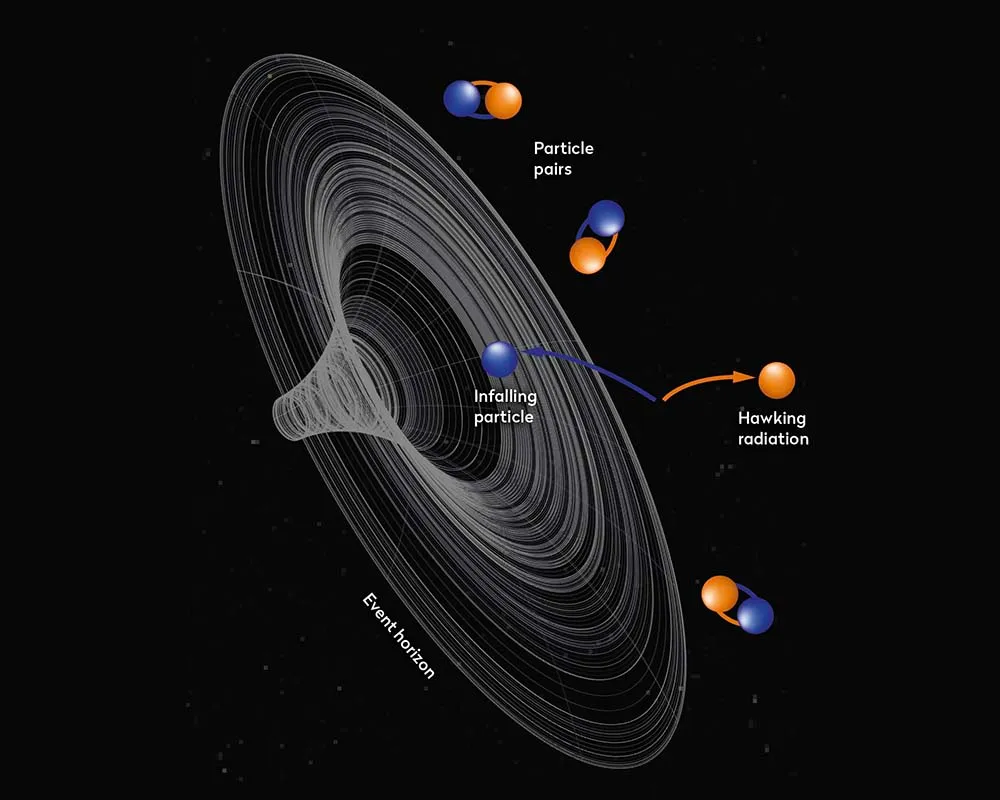

In the sub-atomic world, pairs of ghostly particles are constantly popping into existence before recombining and disappearing again.

Hawking pictured this process unfolding at a black hole’s event horizon – the invisible boundary separating the inside of the black hole from the Universe.

One particle would be trapped inside the black hole, forever separated from its partner on the other side of the event horizon.

Unable to recombine and disappear, the mass of a black hole will decrease as it constantly loses one half of the particle pairs.

In other words, Hawking showed that black holes are slowly evaporating.

While a convincing argument, astronomers have yet to spot Hawking radiation. It’s perhaps why, surprisingly, Hawking was never awarded a Nobel Prize.

His long-time collaborator, Roger Penrose, did win one in 2020 and maybe Hawking would have shared in the prize too had he lived.

Stephen Hawking died in 2018, at the age of 76 – a remarkably long and extraordinary life for a man diagnosed with motor neurone disease at the age of just 21.

Fittingly, Hawking’s ashes are buried in Westminster Abbey, not far from the grave of Isaac Newton.

The headstone depicts the mathematical equation that describes Hawking radiation.

Stephen Hawking's legacy

Since its release in 1988, Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time has sold over 25 million copies and been translated into 40 languages.

It is one of the most famous popular science books ever written.

It appeared on the Sunday Times bestseller list for a record-breaking 237 weeks – although it’s famously a book that a lot of people own but few have finished.

Hawking’s attempt to explain his work on the Big Bang and black holes remains a challenging read for someone with no prior knowledge of astronomy.

In the later part of his life, Stephen Hawking also wrote children’s books alongside his daughter, Lucy.

Very few scientists – if any – have enjoyed the kind of cultural cut-through that Hawking achieved.

Eddie Redmayne won the Oscar for portraying Hawking on the silver screen in The Theory of Everything.

Four appearances in The Simpsons and seven in The Big Bang Theory helped endear Hawking to millions.

This platform allowed him to become one of the foremost science communicators in the world.

His legacy continues even now. In 2015, he launched the Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication, awarded to those who help promote science to the public through media such as cinema, music, writing and art.

This article appeared in the May 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine