It's well-known that the gravitational pull of the Moon is what causes tides on Earth, producing the cyclical nature of the tidal system between low and high tide.

But one factor that has affected the tides over longer timescales is the fact that the rotation of Earth has decelerated over the planet’s history, and that the Moon has slowly spiralled further out in its orbit.

Yes, the Moon is slowly moving away from Earth in its orbit, and this has had an effect on Earth's tides when we compare it over billions of years.

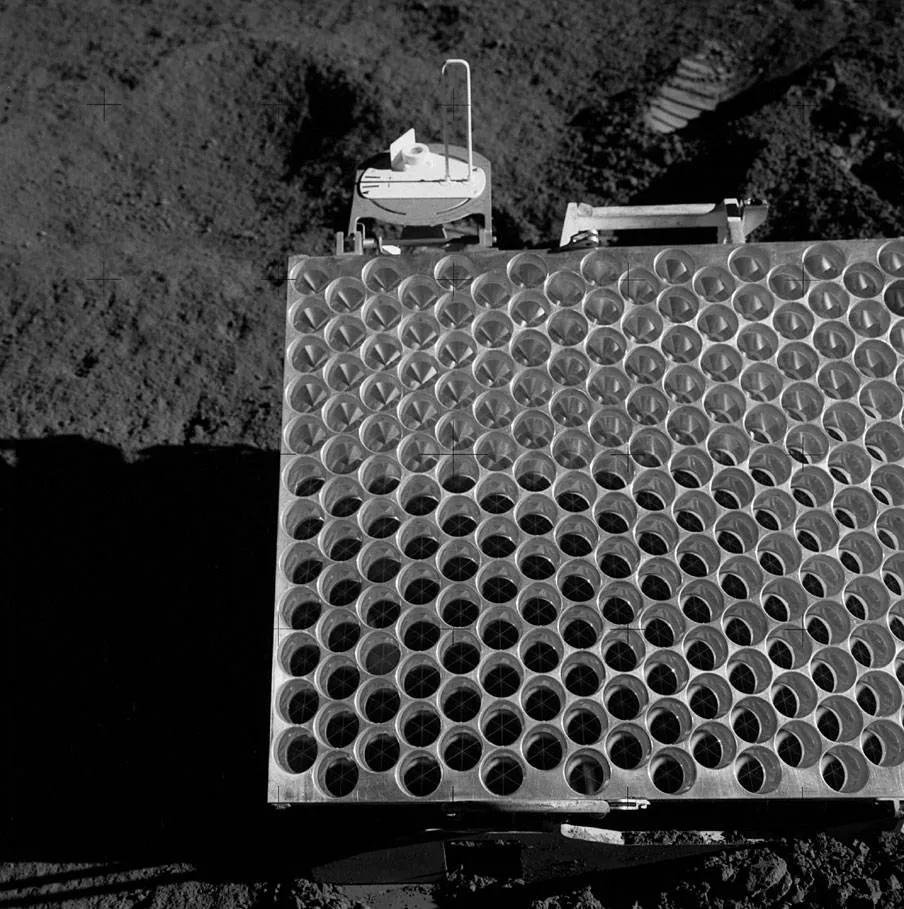

The Moon is drifting away from Earth at a rate of 3.8cm per year, and we know this thanks to measurements taken by a device placed on the Moon by Apollo astronauts, called the Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment.

However, just after the Moon’s formation, our satellite circled much, much closer, and each day on Earth was only around four hours long.

Measuring how much the Moon is moving away

But what’s not clear is exactly how the Earth–Moon system has evolved over the 4.5 billion years since: how have the time Earth takes to rotate and the Moon takes to orbit changed over time?

Computer modelling studies widely disagree. What’s needed are some actual data points from Earth’s deep history.

And this is where geology can provide crucial insights.

Certain kinds of rock were formed from submerged dunes in shallow coastal waters, and show alternating layers of deposited sand and mud, created by strong and weak currents respectively, at different times of the tidal cycle.

Tom Eulenfeld and Christoph Heubeck, both at the Institute for Geosciences, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Germany, reexamined the oldest example of this in the geological record.

It’s known as the Moodies Group sandstone in South Africa, and dates back a staggering 3.22 billion years.

The thickness of these alternating layers cycles every 15 layers, believed to be due to the varying current strengths over the cycle between spring and neap tides over a month.

These geological measurements, combined with the application of Johannes Kepler’s third law of planetary motion, enabled Eulenfeld and Heubeck to reconstruct the rate of Earth’s spin and Moon’s orbital period at the time these ancient rocks were deposited.

They calculate that 3.2 billion years ago the Earth–Moon distance was around 70% of the current value, and that Earth’s rotation rate then resulted in a year of about 700 days, with each day lasting around 13 hours.

Previous measurements of 650-million-year-old rocks from South Australia place the Earth–Moon distance at 97% of today’s separation at that time.

With these points to fill in the gaps, computer models can begin to build a much better picture of how the dance of the Moon around Earth has changed over time.

Find out more about the Moon's influence on Earth in our thought experiment What would happen if the Moon exploded?

Lewis Dartnell was reading Constraints on Moon’s Orbit 3.2 Billion Years Ago from Tidal Bundle Data by Tom Eulenfeld and Christoph Heubeck. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2207.05464.

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.