The samples of lunar rock collected by Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong during the Apollo 11 mission on the Moon were to provide the answers to an intense debate that had developed over the preceding months about how the Moon had formed and what it was made from.

At last, scientists had parts of this alien world to analyse for more definitive answers about the nature of the Moon.

Had it gone through a period of partial or complete melting in its history, or had it formed at low temperatures, its surface features the result of asteroid collisions?

On one side of the debate were the geoscientists, who thought that the Moon was like the Earth, with a dense core – still molten – surrounded by a mantle and a thin crust.

- How the Apollo Moon landings changed the world forever

- 10 facts about the Apollo Moon landings

- Where did the Apollo astronauts land on the Moon?

On the other hand were those with the view that the Moon was an exceedingly different kind of planet, with a surface shaped by forces entirely alien from those that have moulded the surface of the Earth.

The night before launch, American television aired a live debate between geologists on whether lunar craters were volcanic calderas or impact features.

Related to this was the debate raging over how old the lunar surface was.

Most geologists believed it to be hundreds of millions of years old, consistent with the age of Earth’s terrain.

Only a minority argued that the surface was primordial, dating to the time of planetary formation.

Some lunar researchers even speculated that the meandering lunar rilles – long, narrow channels on the Moon – might be evidence for ancient rivers.

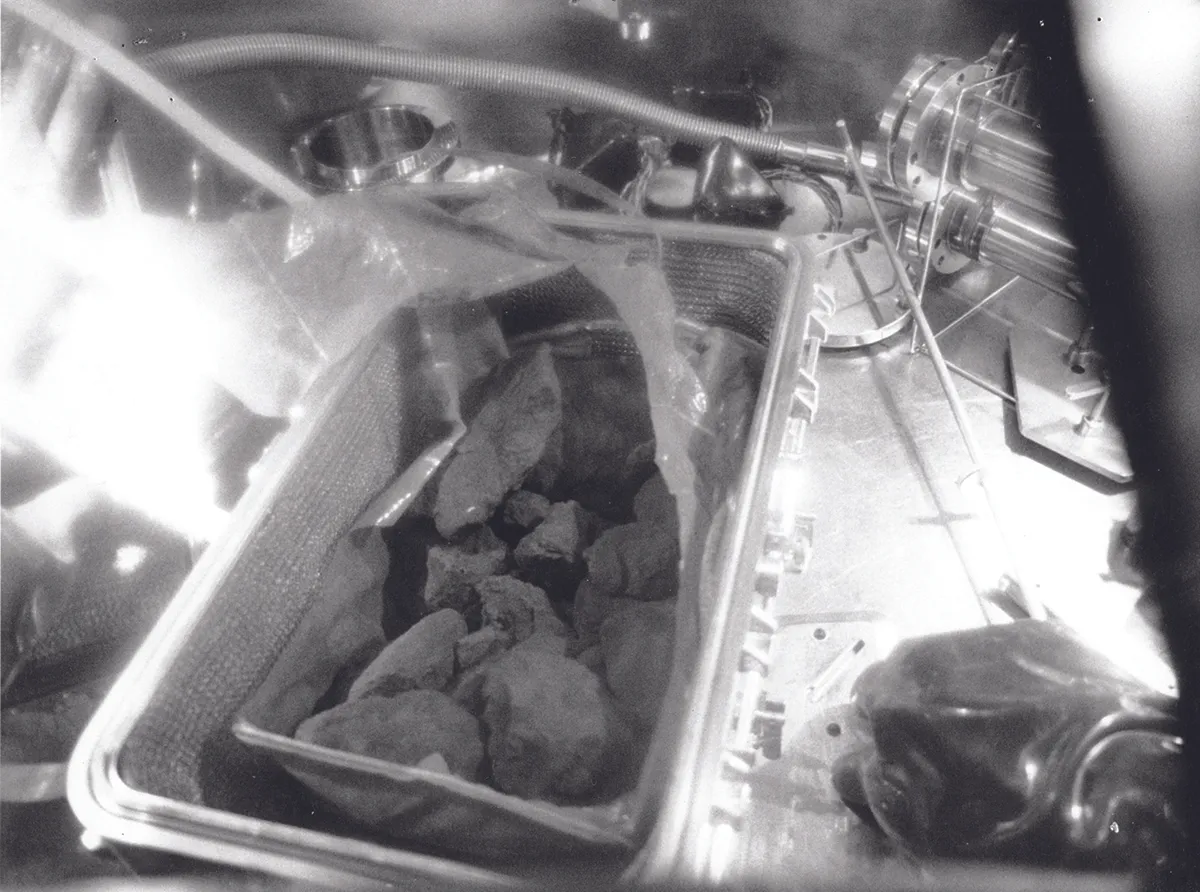

Apollo 11 delivered 22kg of lunar rocks from the Sea of Tranquility for scientific analysis.

One of the first findings was that the main rock type in the collection was basalt, a volcanic rock similar to basalts on Earth.

Here was certain proof that the dark lunar seas, from where the samples were collected, were lava lakes.

But amid small rock fragments, scientists found light-coloured specimens of anorthosite, a rock type made up mainly of calcium-rich feldspar, which was not predicted to be on the Moon.

When the lunar basalt samples were found to be 3.6 billion years old, geologists realised that even younger surfaces on the Moon were older than the oldest existing features on Earth.

The colour suggested that these few fragments had come from the light-coloured lunar highlands, a considerable distance away.

Anorthosite is relatively rare on Earth, and the vast volume of this rock spread over most of the light-coloured surface of the Moon seemed peculiar indeed.

The situation required a radical idea to explain it, and this was provided by Prof John Wood, then a planetary scientist at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

His 1970 hypothesis built on earlier theories that the Moon was formed from a collision between the young Earth and a body the size of Mars, and it has stood the test of time.

He suggested that as material came together to form the Moon, so much heat built up that its entire surface became covered in a global magma ocean 100km deep.

In this molten rock, the lighter feldspars rose to the surface to form a crust of anorthosite, which slowly cooled to become the light-coloured lunar highlands.

The magma ocean concept was new but is now widely accepted as an early stage in the formation of all the terrestrial planets, including the Earth.

Intense bombardment

The sample collection also included rocks made of fragments that had been melted together by the heat from asteroid and meteorite impacts.

Known as breccias, these testified to the intense bombardment the lunar surface underwent in its history.

All the samples showed that the Moon was dry and lifeless, and there were absolutely no organic compounds.

The Apollo 11 samples were also pivotal in dating the lunar surface.

Geologists had inferred that more densely cratered surfaces were older, but there was no way of knowing how old.

When the lunar basalt samples were found to be 3.6 billion years old, geologists realised that even younger surfaces on the Moon were older than the oldest existing features on Earth.

Scientists now estimate that 80 per cent of what we know about the Moon came from the Apollo 11 samples.

And the findings went further, having a huge impact on ideas about the early history of our own planet and the formation of the Solar System.

Dr. Wendell Mendell is a planetary scientist who retired from NASA in 2013. This article originally appeared in the Man on the Moon special edition magazine.