Did stars form and then migrate into galaxies, or did galaxies form with stars in place: which came first?

Astronomers have managed to piece together pretty confidently the story of what occurred after the Big Bang, the point at which the Universe was 'born'.

We know about the time when the Universe was transformed from a hot, dense primordial soup of ionised gas to the time when the first electrons and protons combined to form the first neutral atoms.

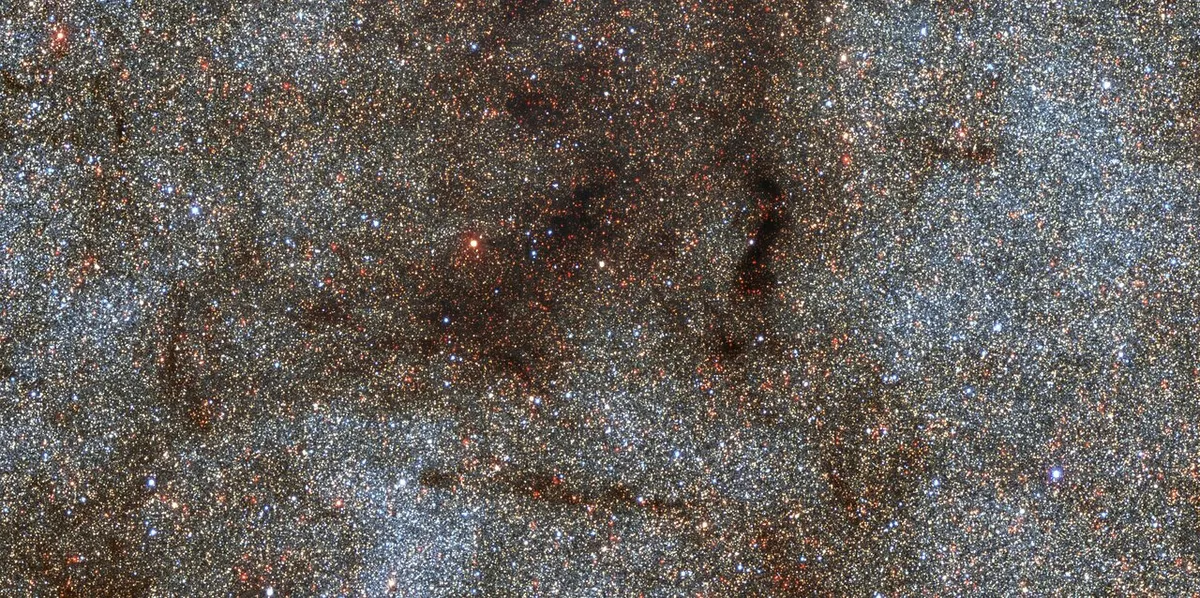

The Universe cooled, the first stars formed and spread light across the Universe.

We know much about what happened during the first few seconds of the Universe, and how the first stars affected the evolution of the Universe.

Today we know that of stars, black holes, cosmic dust - and the mysteries substance known as dark matter - make up massive structures known as galaxies.

Some galaxies are spiral-shaped, some are irregular, some are elliptical.

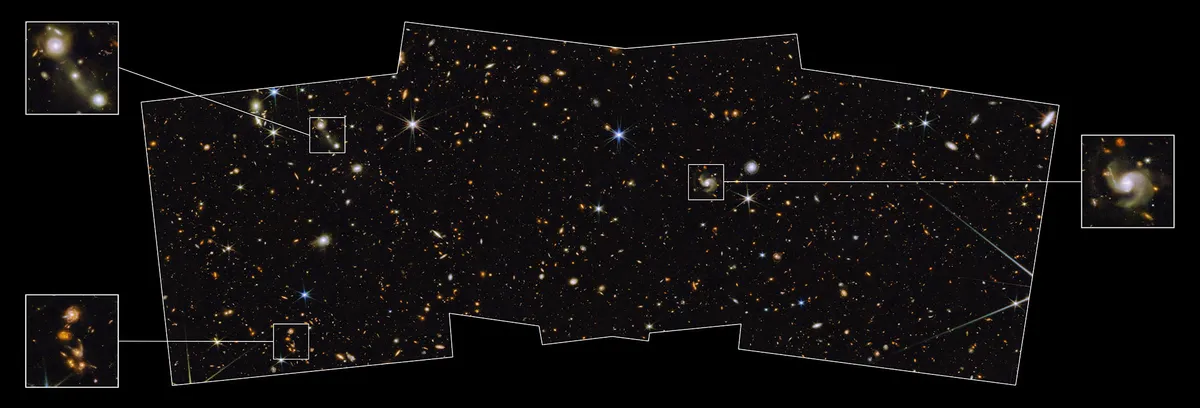

But which came first? After the Big Bang, did stars form first and then gather into galaxies, or did the first galaxies form with stars in place?

It’s something of a chicken-and-egg question, but actually, neither of these things happened. That is if, by galaxies, you mean galaxies as we know them today.

According to the best current estimates, the first objects began to congeal out of the cooling gas of the Big Bang fireball about 200 million years after the beginning of the Universe.

These objects had to be so massive that their self-gravity was strong enough to crush them against the force of the hot gas pushing outwards.

Shortly after the Big Bang it took the gravity of a relatively large mass to shrink a gas cloud because the gas of the Big Bang was so hot.

Consequently, the first objects in the Universe – dubbed ‘mini-haloes’ – had the mass of roughly a million suns, only about 0.001% of the mass of a big present-day galaxy.

It was in these objects – galactic fragments, if you like – that the first so-called Population III stars are believed to have formed.

Over time, the mini-haloes merged and merged again, eventually making big galaxies like the Milky Way and Andromeda that populate today’s Universe.

This article originally appeared in the March 2009 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.