The Winchcombe meteorite was found after a lot of observations of a fireball on 28 February 2021.

That morning, a family in Gloucestershire had found this pile of grey dust spread out on their driveway with some bigger chunks sitting on top of it. They picked up the bigger bits using aluminium foil and put them in a sandwich bag.

Ashley King, who is a meteorite specialist at the Natural History Museum and helps the UK Fireball Network, went on local television and radio in Gloucestershire and alerted people, saying "If anybody’s got any unusual rocks that weren’t there yesterday, send me a picture."

Read more:

- Ann Hodges: history's only meteorite victim

- The story of the Beddgelert meteorite

- How dogs can help meteorite-hunters

As a result we got loads of pictures, but there was only one that might have been a meteorite.

King asked my colleague Richard Greenwood if he could go have a look. And, yes, it was a meteorite, which is brilliant!

I then started putting into action our recovery team along with colleagues from the Natural History Museum, as well as Imperial College London and the University of Manchester, but you can’t just start wandering around people’s fields and driveways in the time of a pandemic, so there was a lot of admin.

Fortunately, everybody seemed to drop everything as they realised that this was something special.

Analysing the Winchombe meteorite

The Winchcombe meteorite was seen on Sunday 28 February, identified on Wednesday 3 March at lunchtime and by Thursday 4 March we had it in a mass spectrometer at the Open University.

By Thursday night we had classified it. We reckon this is the fastest journey from an asteroid to a laboratory – certainly in UK history and possibly in global history – because it was collected and analysed so quickly.

There is some analysis that has to be done instantly: though the meteorite isn’t radioactive it does contain some isotopes which decay on a very short timescale – a matter of days.

Those can help us calculate how big it was before it actually came through the atmosphere.

There are a couple of other tests that need to be done quickly, because even though it’s sitting in clean conditions, the longer it’s on Earth, the more chance it will be contaminated.

There are also minerals which might lose their water and a lot of very volatile organic compounds. I haven’t sniffed it yet, but my colleague said it smells like compost and that’s those organic volatiles escaping. We usually lose those and don’t get a chance to analyse them.

After that, we’ll take a chip of rock, embed it in resin and polish it to see what the surface looks like and what minerals are in there.

What are meteorites?

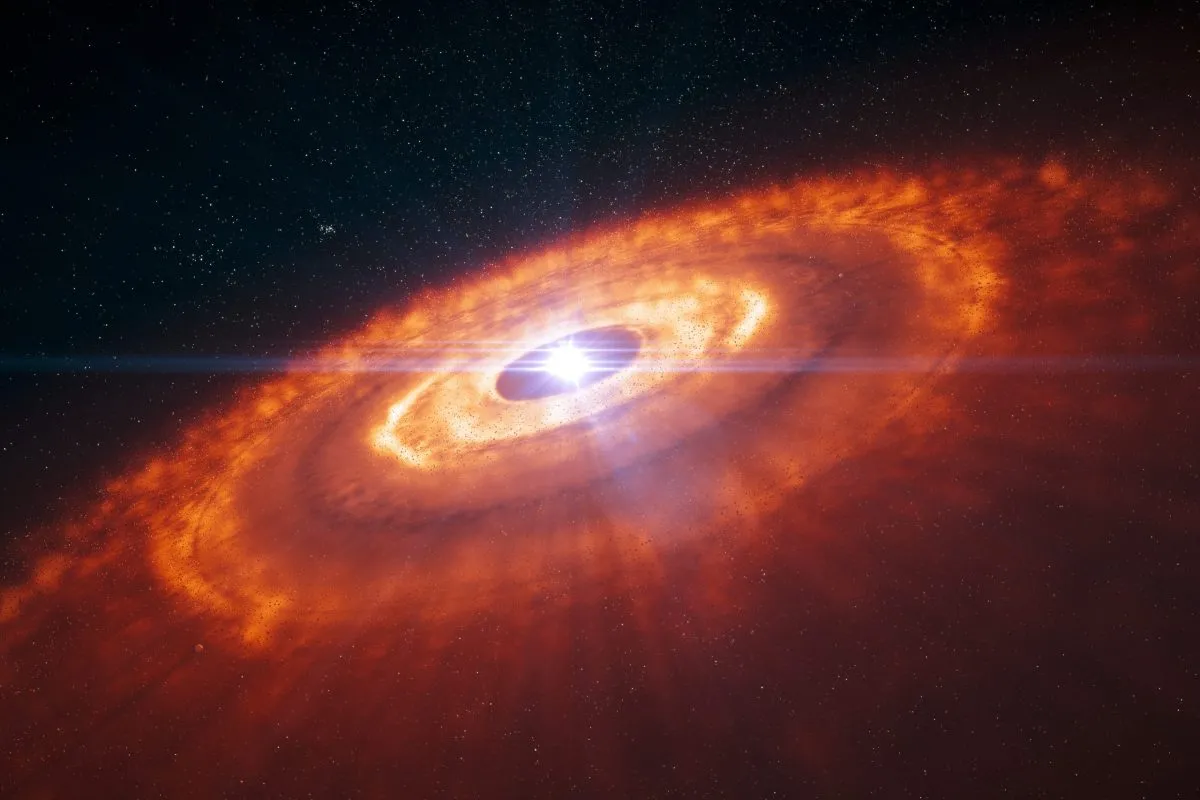

Meteorites come in two groups – primitive and processed.Primitive ones are made from dust left over from when the Solar System formed.

Processed meteorites have been part of a planet at some point. These tell you about planetary cores and surfaces.

The Winchcombe meteorite is a primitive meteorite, so it’s unchanged since the dawn of the Solar System.

It’s a particularly exciting type because it’s a carbonaceous chondrite. It’s got lots of organic compounds in it, which are the stuff which eventually formed life.

We’re looking at a meteorite that contains the building blocks of life.

The Winchcombe meteorite: as it happened

The story of the Winchcombe meteorite was first reported by BBC Sky at Night Magazine on 9 March 2020 in our Astronomy News section.

Fragments of a rare type of meteorite have been recovered from a driveway in Winchcombe, Gloucestershire, marking the first recovery of a meteorite in the UK for 30 years.

The fragments weigh just over 300g and have been taken to the Natural History Museum (NHM) for analysis.

The samples could give scientists an insight into the conditions of the early Solar System and its evolution over time.

The news follows observations of a fireball that was seen over the UK and Northern Europe on 28 February.Fireballs are space rocks that burn fiercely bright in the sky as they enter Earth's atmosphere.

This particular space rock was travelling almost 14km per second before entering the atmosphere and falling as a meteorite. Fragments of this meteorite have now been recovered.

It is the first time since 1991 that a piece of space rock has landed and been recovered in the UK.

Meteorites and other space rocks are particularly important because they are relics left over from the Solar System, and can be used to analyse what our cosmic neighbourhood might have been like as it was beginning to form.

The meteorite that has been recovered is known as a carbonaceous meteorite.

"There are about 65,000 known meteorites in the entire world, and of those only 51 of them are carbonaceous chondrites that have been seen to fall like this one," says Prof Sara Russell, a researcher at the NHM who studies this variety of meteorite.

"It is almost mind-blowingly amazing, because we are working on the asteroid sample return space missions Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx, and this material looks exactly like the material they are collecting."

On Sunday evening, residents of a house in Winchcombe heard a loud rattling noise. Next morning they went outside and found a dark, sooty mark on the driveway outside their house.

They collected the fragments and contacted the UK Meteor Observation Network.

"For somebody who didn't really have an idea what it actually was, the finder did a fantastic job in collecting it," says, Dr Ashley King, a researcher at the NHM who studies meteorites.

"He bagged most of it up really quickly on Monday morning, perhaps less than 12 hours after the actual event. He then kept finding bits in his garden over the next few days.

"It looks a bit like coal. It is really black, but it is much softer and is really quite fragile. It is exciting for us because more this type of meteorite is incredibly rare but hold important clues about our origins."

Carbonaceous chondrites like the one discovered originated from an asteroid that was formed when the planets of our Solar System were in their infancy.

At this stage, the planets would have been pieces of cosmic material coalescing in a dusty disc surrounding our host star, the Sun.

"Meteorites like this are relics from the early Solar System, which means they can tell us what the planets are made of," says Sara.

"But we also we think that meteorites like this may have brought water to the Earth, providing the planet with its oceans."

The fireball that preceded the meteorite find was witnessed by about 1,000 people and reported to the UK Meteor Observation. This, combined with data collected by the UK Fireball Alliance, is giving scientists greater insight into the story behind the discovery.

There are about 65,000 known meteorites on Earth and more than 1,000 the size of a football are thought to land on our planet in a year.

But only 1,206 have been seen falling and, of these, only 51 are carbonaceous chondrites.

For more on this story, visit the National History Museum website.

Monica Grady is Professor of Planetary and Space Sciences at the Open University. Follow her on Twitter @MonicaGrady.