The origins of the aurora rest with our star. The Sun is always throwing out charged particles – mostly electrons and protons – in a moving plasma that we call the solar wind.

Sometimes it releases more matter into the Solar System when the twisted magnetic field lines of the Sun break in a solar eruption or even a giant coronal mass ejection.

A coronal mass ejection is enormous! The Sun throws billions of tonnes of matter out into the Solar System, travelling at millions of kilometres an hour.

We and all the other planets in the Solar System sit in this turbulent sea of plasma. This solar wind is constantly buffeting the Earth, sometimes weakly, sometimes strongly.

- How to detect the aurora with a homemade magnetosphere

- Visiting Swedish Lapland for the Northern Lights

- Best readers' images of the aurora

All these fast charged particles would be dangerous to life, but Earth has a magnetic field, that forms a protective shield called the magnetosphere.

The solar wind interacts with Earth’s magnetic field, and if the magnetic field in the solar wind points southwards, the interaction is particularly strong; it sets up a cycle of changes in Earth’s magnetic field pattern.

This is called the Dungey Cycle and involves magnetic field lines being opened on the sunward side of the planet and closed again behind in a process called magnetic reconnection, where magnetic field lines snap and rejoin in a different configuration.

This explosive process accelerates electrons into the Earth’s atmosphere on the night side of the planet, causing the aurora.

The aurora is the way our planet protects itself from the battering of the solar wind, absorbing the energy in its magnetic field and dissipating it in a beautiful light show.

Canada has a particularly wide view of the auroral canvas and this has shaped the way auroral research is done there. In August 2014 I visited a couple of these observatories – the Athabasca University Geophysical Observatory in Athabasca, and the AuroraMAX observatory in Yellowknife.

I was researching a book about the Northern Lights – a natural step for a plasma physicist with a fascination with mountains and snow.

It was a journey that took me to various Arctic locations learning about the culture, folklore, landscapes and science of the aurora.

The science itself is fascinating and varied, combining astronomy, geology, magnetism, atomic physics and more.

The breadth of Canada’s auroral zone means scientists can cover a range of spatial scales in their research: what this means is that they can look in detail at a small area or more broadly at a wide area.

Researchers in Scandinavia, with their narrow slice of the auroral oval, use high-tech instruments to make detailed measurements on the smaller scale. Satellites can look at the large, global scale.

Those in Canada can look at the mid-scales with fairly cheap instruments spread over a large region.

Funding has been put into setting up the wide infrastructure, stretching from the east coast at Goose Bay to Inuvik in the far northwest, and managing the large amounts of data that are generated.

The approaches are different yet complementary, but they are shaped by the landscape and geographical advantage.

There are tens of these observing stations with similar cameras dotted around the large country.

In Athabasca it was a six-domed facility housing other instruments; in Yellowknife, a wooden garden shed with a dome cut into the peaked roof.

This and electricity are all you need for automated auroral imaging.

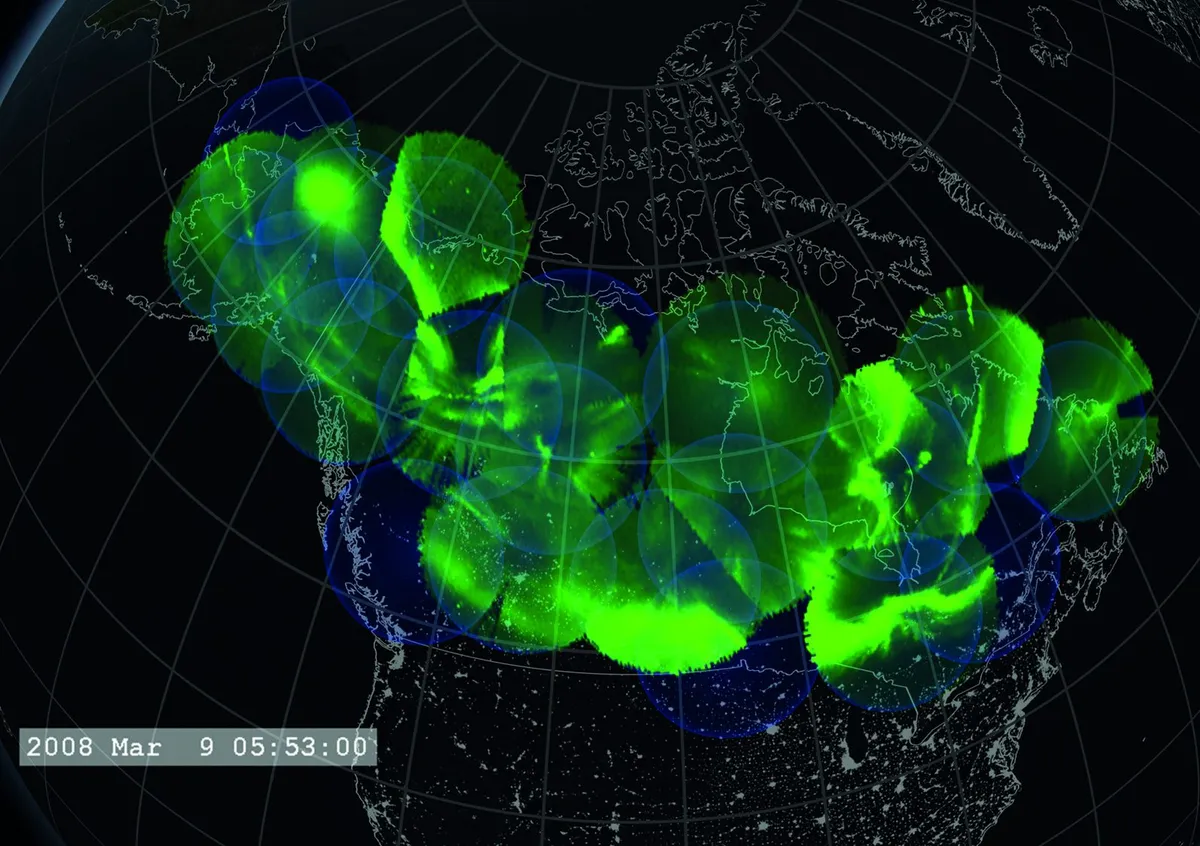

The observing stations are fitted with commercial CCD-based digital cameras that have been modified with state-of-the-art lenses by a team at the University of Calgary, and topped by a fisheye lens to give a wide, circular field of view.

Pointing directly upwards, the cameras look out in a cone from horizon to horizon, so they’re called all-sky imagers.

Up at the altitude of the aurora (around 100km), the field of view is about 1,000km across, so when the images of several cameras are merged together they form a mosaic of aurorae across the entire continent.

The cameras turn on at nautical twilight, collect images every six seconds and transmit data via satellite in real time.

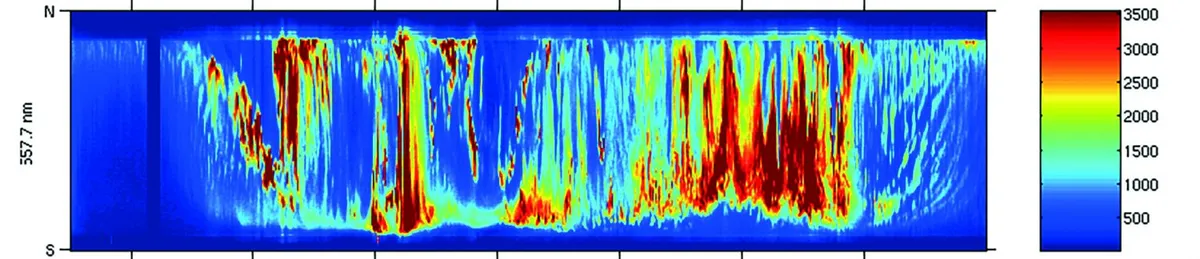

Data from these cameras’ all-sky images is often analysed by turning it into a keogram, which broadly shows how the aurora varies over a night, both over time and over the ground.

These go back to the time when we couldn’t make moving videos of the aurora so easily, though they still have scientific value now for quick reference and easy publication.

Keograms are made by taking a single north-south slice from the centre of every all sky image taken throughout a night.

These are then lined up sequentially from left to right. This creates a kind of graph where the X-axis is time and the Y-axis is sky position relative

to the camera; the bright parts show the position of the auroral arc.

Keograms show the north-south movement of the aurora over time, which in turn provides information about the changes occurring in Earth’s magnetic field.

This information is important to auroral physicists because although the cyclical process that causes the aurora – known as the Dungey Cycle – is now

an established concept, there are still elements of the process that scientists don’t understand.

The magnetic reconnection that causes the aurora is triggered by instabilities that scientists are still trying to fathom.

“What causes that instability to start the reconnection process and start closing off the magnetic field on the night side is not well understood,” says Jim Wild, professor of space physics at Lancaster University.

“Quite what the mechanism is – and where that starts – is one of the big questions.”

Even now we have space-based measurements, images from the ground are still valuable. It’s the combination of technologies that provides the greatest insight.

The advantage of imaging from the ground is better resolution; a downside is clouds blocking the aurora from view.

Specialist all-sky imaging enables scientists to locate particular features of the aurora.

“You can work out the position of the feature from some relatively straightforward geometry,” says Wild. “There’s lots you can do with this quite simple technology.”

Studying the auroral features gives insight into the mechanisms out in the magnetosphere – instabilities, wave activity, motions of plasma and boundaries.

The aurora we see is like the image projected onto a screen created by a disturbance further out.

Back in Yellowknife, I met with James Pugsley, president of the Astronomy North Society, who is responsible for local support of the observatory.

He’s also the voluntary local lead on the AuroraMAX outreach project. He sees it as a huge opportunity to be able to support and promote the science.

“If observation is the key to making discoveries then I will do it! I will go out and watch the aurora for the greater good,” he jokes.

But it is fascinating how through this outreach, the Northern Lights are able to stir something deep inside us – an awed, spiritual response – even though their origins are no longer a mystery.

There is still more to know and one thing is certain; people will be watching and studying the aurora for a long time to come.

What is the auroral zone?

Earth has a magnetic field rather like a bar magnet in space. The geomagnetic field is fundamental to the creation of the aurora, where charged particles are accelerated down magnetic field lines into Earth’s atmosphere, so auroral activity occurs in a ring centred on the magnetic poles.

The auroral zone is the land above which we generally see the aurora, by definition at midnight.

It is a band demarcated by magnetic latitude, stretching approximately 1,300km between around 61°N and 73°N magnetic, based on probability.

Magnetic latitude differs from geographic latitude because Earth’s magnetic axis is not orientated precisely north-south; it is tilted towards Canada in the northern hemisphere, so the auroral oval reaches to lower latitudes in North America than on the other side of the planet.

The vast majority of land situated in the auroral zone belongs to Canada.

How to plan your own aurora trip

The aurora is one of Earth’s most spectacular natural events, a captivating light display that is profoundly touching.

Seeing it is on many people’s bucket lists, but it’s certainly not guaranteed and this elusiveness provokes a feeling of gratitude when you do see it.

So where should one go, and how? Well there’s one essential requirement – you need to travel into the auroral zone to give yourself the best chance.

There are quite a few options for how to get into this zone: a scheduled cruise, an aurora-hunting flight, a ground-based tour or a DIY adventure.

Which will you choose?

If you'd like to do a bit of practical astronomy during your aurora trip read our guide to the best telescopes for astronomy travel.

1

Aurora flights

Don’t have the time or inclination to spend a week in the frozen north, but still want to see the aurora?Consider taking an aurora flight – an evening excursion to sub-Arctic airspace during which you can see the aurora from above the clouds.

I took an aurora flight from London Gatwick. The flight was scheduled for 9pm, after a lecture-style briefing all about the aurora and the flight itself.

Alas, the aurora decided not to make an appearance for us that night, which is fairly unusual we were told. However, I have been fortunate to see the aurora from commercial aircraft during trips to the Arctic.

Seeing the aurora from a plane and through a small window can’t compare to seeing it in an Arctic landscape. But for a quick, easy and fairly cheap way to see it, it’s a great start.

- Prices from £219.95 per person

- Melanie travelled with Omega Holidays

- www.omega-holidays.com

2

Take an aurora cruise

Cruising is a comfortable way to experience the vast wilderness of the Arctic, though one that I have yet to try. A colleague went on an Alaska cruise last May, but didn’t see the Northern Lights.

The problem is that from May to September, when the weather’s good enough to cruise in the Arctic, the skies are no longer dark enough to see the aurora – though you might get lucky at the very ends of the season.

However, smaller more specialist cruises run outside these months, and they can access more of the coastline than the bigger ships.

The Small Cruise Ships Collection has some Northern Lights voyages, and Discover the World runs a cruise to Greenland.

In Norway, there is also the Hurtigruten – a daily passenger and freight ferry that runs along Norway’s coastline, also offering packages with flights from the UK.

3

See the aurora on a van tour

Van tours are great if you’re staying in town and need to get away from the lights, or if you’re worried about clouds blocking your view.

Tour guides will monitor auroral activity, have experience of the region and know where to drive to find clear weather.

I went on a van tour from Alta in northern Norway in March 2014 and saw a quiet aurora display.

Of course, there may be a lot of driving involved and you may end up watching the aurora from the side of the road, but if you’re holidaying in a built-up area then a van tour will give you the chance of seeing something away from urban lights.

- Melanie travelled with GLØD Explorer from Alta on a public tour

- www.glodexplorer.no/en/hunting-northern-lights

4

Wilderness camping and cross-country skiing

If you are feeling adventurous then a cross-country ski tour is a wonderful way to experience an incredible wilderness environment.

But you might not want to go in February like I did.I skied out across Spitsbergen in Svalbard with a personal guide for a week in February 2015.

After the first day we didn’t see a single other person. It was vast and beautiful, but freezing.

The downside to this is that when it comes to the Northern Lights, you don’t want to get out of the tent!

That might sound crazy, but it’s true: your priorities completely change when you’re in such an intense situation.

Going in spring when it’s a bit warmer but not so late that it’s too light for the aurora would be a good compromise.

- Melanie travelled with Newland Expeditions on a bespoke trip

- www.newland.no

5

DIY aurora travel

If an organised tour or cruise doesn’t appeal, consider travelling to somewhere within the auroral zone and doing your own thing.

With a car you can drive around to see the sights or find clearer weather for aurora spotting.

If you choose to stay in town, then for the best aurora viewing you should drive out at night to a dark, clear, picturesque spot.

You could also choose somewhere rural where you’ll be able to watch the aurora from your door.

Just keep the lights down low inside or you’ll ruin your night vision and you won’t see the aurora so well.

- Prices vary with location, standard of accommodation and car choice

- Melanie stayed mainly in private accommodation. In Karasjok she stayed at Engholm Husky Lodge

- www.engholm.no

6

Aurora lodge stays

A remote lodge in the auroral zone is a base for a relaxing holiday, with a good chance of seeing a display thrown in.

At a lodge in the right location, somewhere away from light pollution, all you have to do is put on some extra layers and go outside after dinner.

If you’re lucky like I was during a lodge stay in Canada in February, the aurora will be waiting for you almost every night.When you get cold or tired, the lodge is right there with roaring fires and hot tea.

Some resorts even offer bedrooms in glass bubbles or igloos, from which guests can watch the aurora lying in bed.

It’s also worth checking out the seasonal activities available at different lodges too. You may get to try out cross-country skiing or snowmobiling, or a dogsled ride.

- Melanie stayed at Blachford Lake Lodge in Yellowknife, Canada, and Engholm Husky Lodge in Karasjok, Norway. She has visited Hotel Rangá in Iceland

- www.blachfordlakelodge.com

- www.engholm.no

- www.hotelranga.is

Dr Melanie Windridge is a plasma physicist, speaker, writer and author of Aurora: In Search Of The Northern Lights.