If you can find Polaris, the North Star, you can find north, because the North Star always points north in the night sky.

Sailors have used the stars for as long as there have been sailors to be guided by them, but as time has gone on, that set of skills has fallen away for most of us.

Still, here in the northern hemisphere, we’re fortunate and have one trick left up all of our sleeves, and that's knowing how to find the North Star.

Why finding the North Star is important

Knowing where the stars sit in the night sky is important in general, but knowing how to find the North Star could very well save your life!

A few Octobers ago, my family and I were visiting some friends in the mountains of Vermont. After dinner, I went out to get a better look at the skies.

The dark in their small town is deep and all-encompassing; a very welcome change from the light-polluted and washed-out skies of my over-lit railroad town.

Before long, as I strolled along staring at Mars, I was more concerned about coming across a bear than I was about where I walked.

I had no idea how to get back; no signal on my mobile phone, either. I was lost.

It’s always interesting to me how very dark and starry skies can be disorienting.

They’re wonderful, no doubt, but with so many stars around, it’s sometimes hard to pick out the familiar ones.

Light pollution causes its own problems, but it also manages to highlight the sky’s brightest stars.

What is the North Star?

The star Polaris (α UMi) is called the North Star because it’s very close to, though not exactly on, the north celestial pole.

That’s the spot we’d be looking at if we were to take Earth’s north pole and stretch it way off into space: Polaris, the North Star, is almost exactly due north.

Because the whole sky seems to rotate round this region, it's often used by astrophotographers to shoot star trail images.

Close up, Polaris would appear as a giant star about with five times the Sun’s mass and two other stars that are around the same mass as the Sun.

As long as we can find that star, it’s easy to figure out where we are and what direction we’re looking. The other cardinal directions are just as easy to figure out from there.

What’s more, since it’s so close to the north celestial pole, Polaris always at the same altitude above the horizon as your latitude.

For example, in London, which is at about 51° north latitude, we can see Polaris about 51° above the horizon.

Meanwhile, where I live Polaris is lower, around 41 degrees from the horizon.

How to find the North Star

Though the North Star is one of the most famous stars in the night, it is by no means the brightest star in the night sky.

It isn’t as bright as many of us expect. Truth is, it’s only about the 50th brightest star in the sky.

The North Star is in the constellation Ursa Minor, and the star can be tough to find in brightly lit suburban or city skies where the rest of the constellation is nearly completely washed away.

From the 430 or so lightyears from us to it, it appears as a single, second-magnitude dot in the night.

We don’t need to be lost in the mountains to look for the North Star, though. In fact, I usually start my evenings looking for it, even if I’m in my own yard.

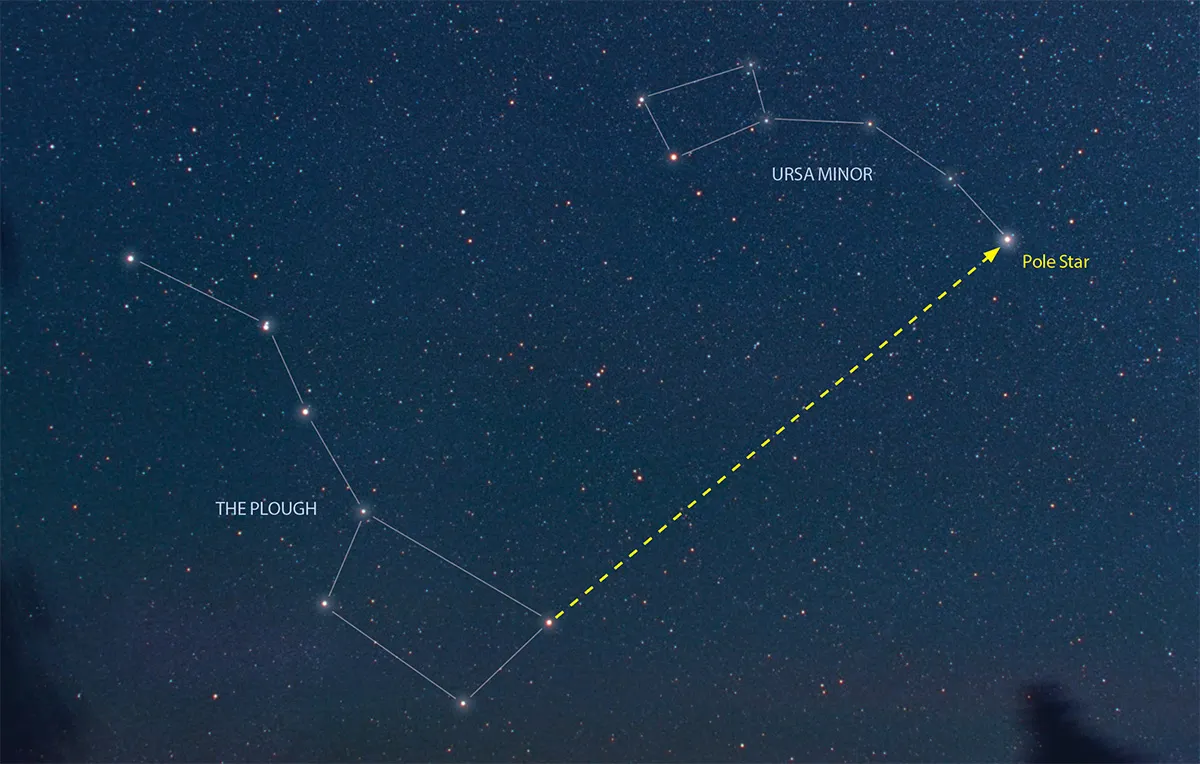

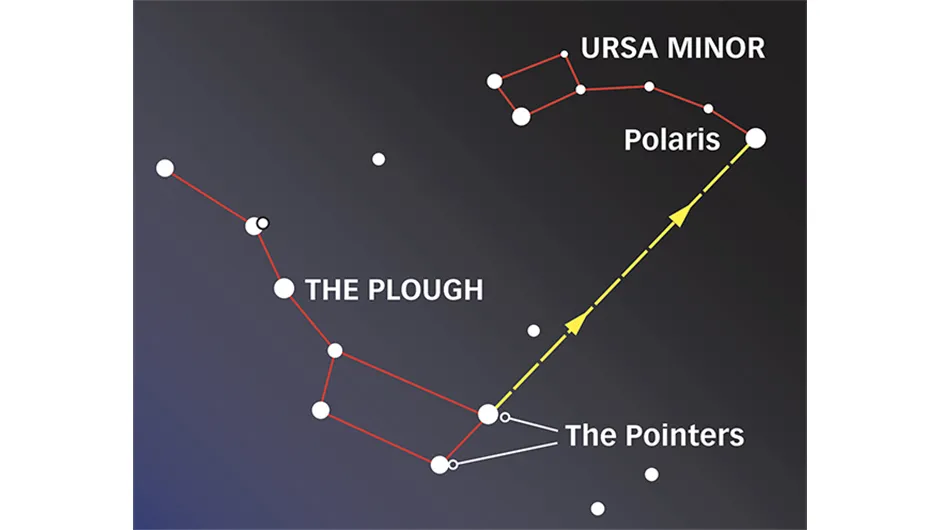

You can find the North Star very easily once you've found the the Plough, which is one of the most familiar patterns in the sky, and is always visible since it's part of the circumpolar constellation Ursa Major.

For much of the northern hemisphere, all the stars in this region of the sky are circumpolar.

This means they’re so far to the north that they don’t rise and set as other stars do, and they don’t come and go with the seasons.

Instead, they’re in the sky every night of the year and never set. They just get overwhelmed by bright sunlight every day, and then reappear through the twilight each night.

Cassoipeia, Cepheus, Draco and objects in that part of the sky are also all circumpolar, and it’s exciting to show people who are new to the skies how to find those, too.

To find the North Star using the Plough, draw a line between Merak and Dubhe, two stars at the end of the Plough’s blade, then out through the blade’s top. The next fairly bright star is Polaris.

That’s all there is to it, and once we find it, we’re on our way! East is to our right, west to the left, and south is behind us.

It was just a couple quick turns and a few minutes’ walk before I was back at my friends’ place.

Will Polaris always be the North Star?

Polaris hasn’t always been the North Star, and it won't always be the North Star.

Earth’s axis wobbles a little bit. Over time, thanks to this precession, it points toward different stars over a 26,000-year cycle.

About 12,000 years ago, it pointed towards Vega (α Lyr) in the constellation Lyra, and also part of the Summer Triangle asterism (one of our favourite summer constellations and asterisms).

Though things look steady now, our axis is gradually drifting so that in about 12,000 years Vega will become the north star again.

While our stellar navigation skills aren’t what they used to be, we can still rely Polaris to guide us home and learn our way around the northern part of the sky. Plus it’s a great party trick.