What were the first things you learnt about astronomy, after the names of the planets and the phases of the Moon? It was probably that the groups of stars we see each night are called constellations. That’s on the right track, but not entirely true.

People have seen patterns among the stars for as long as there have been people to see them. If you’ve ever had the chance to be under a deep and disorientating dark sky, it’s not hard to imagine what our ancestors saw and spent their nights talking about.

Find out which constellations are visible all year round in our guide to circumpolar constellations.

In the Western tradition, it was the third-century BC Greek poet Aratus that first set out a description of 43 constellations, which Ptolemy developed into a list of 48 in the second century AD.

The patterns were amended over time, but for the most part lasted until 1922, when the International Astronomical Union (IAU) refined the list, but also made one very important change.

They defined constellation borders and, with those borders, defined the modern, official 88 regions that cover the sky.

This means, for example, when we talk about Gemini, Cygnus or Ursa Major, these days we’re referring to an entire region of the sky; the stars within are like the constellations’ big cities, shining in the distance.

This definition wraps each constellation around its stars and is particularly useful for identifying far away galaxies and finding our way back to them.

Asterisms, on the other hand, are informal but recognisable star patterns, which can be part of one or more constellations.

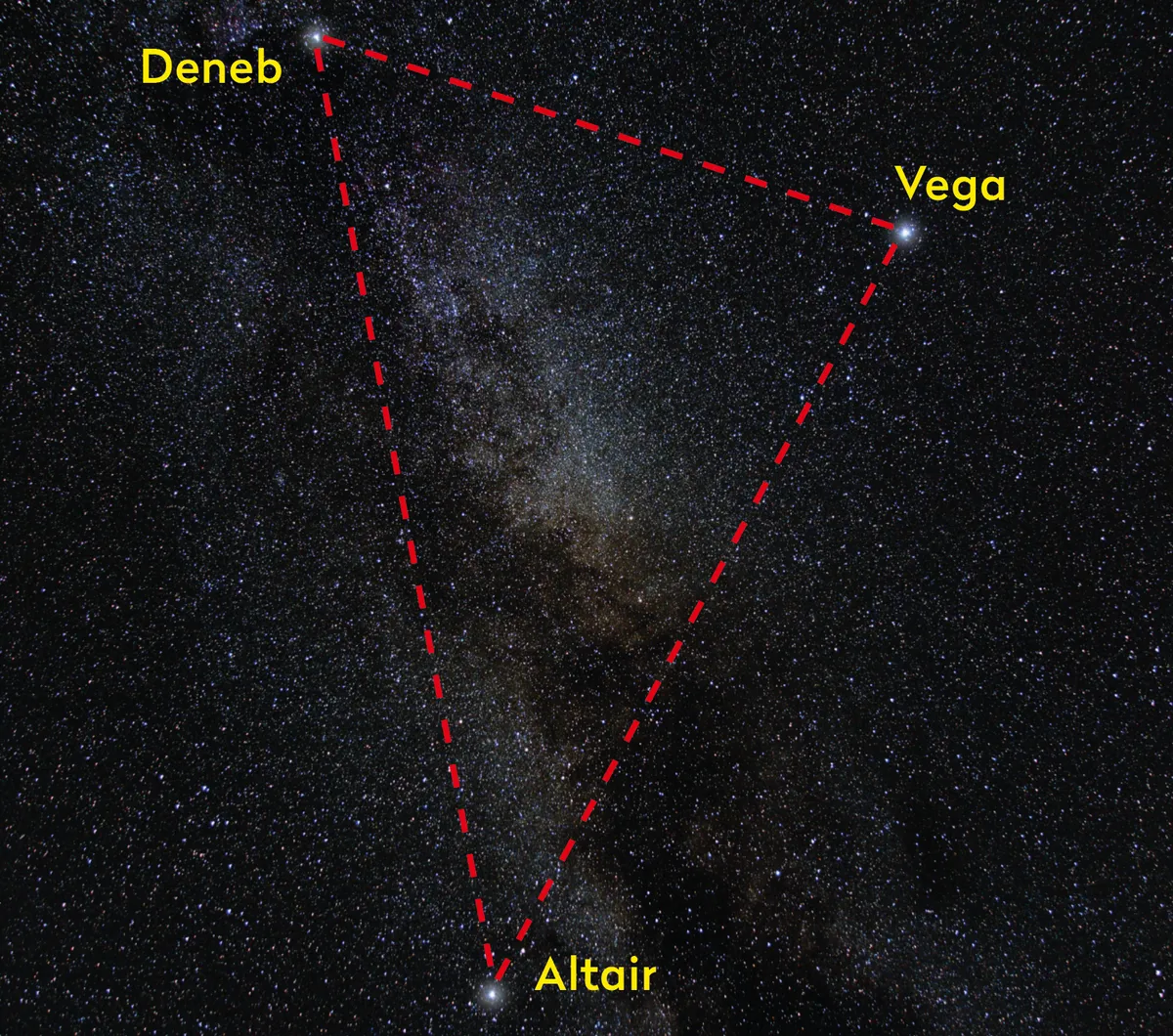

So while all the stars of the Plough or Big Dipper – perhaps the most famous asterism of all – are within the constellation of Ursa Major, the three stars of the Summer Triangle asterism (see chart at the top) are each in different constellations: Vega (in Lyra), Altair (Aquila) and Deneb (Cygnus).

The stars you think of as ‘Orion’ are that constellation’s asterism. You can find the Hunter’s main asterism, with Betelgeuse at one shoulder and Rigel at a knee, without much trouble throughout autumn, winter and into spring.

That group is within a much bigger asterism, the Winter Hexagon – six first-magnitude stars in six constellations: Capella (Auriga), Pollux (Gemini), Procyon (Canis Minor), Sirius (Canis Major), Orion’s Rigel and Aldebaran (Taurus).

Many think of the three stars in Orion’s Belt (Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka) as another asterism. His Sword is one too, and if you look closely at its middle star, you’ll see it’s not a star at all, but the Orion Nebula.

Glowing within all that dust is the Trapezium Cluster which, even with a small pair of binoculars, can be seen as an asterism of three or four stars.

What you have is a small asterism (Trapezium) located within a bigger one (Orion’s Sword), which is itself within Orion’s main asterism – and all of these are tied together within the enormous Winter Hexagon asterism.

You can even come up with your own asterisms, maybe ‘The Great Office Chair of Corvus’, or ‘The Perfectly Straight Line of Four Dim Stars Near Cygnus’?

Thinking up patterns gives you a chance to find your way around the sky on your own terms. Why not head out and make some up tonight?

4 asterisms to spot in the night sky

See if you can spot these four famous asterisms as they appear in the night sky throughout the astronomical calendar

The Plough and the ‘W’

The Plough and a ‘W’ shape formed by Cassiopeia’s brightest stars appear to circle around Polaris, the North Star, every night. Use pointer stars Merak and Dubhe at the Plough’s front to find Polaris, then continue to Cassiopeia. If the skies are dark enough, you may be able to make out the rest of Ursa Minor’s dim stars.

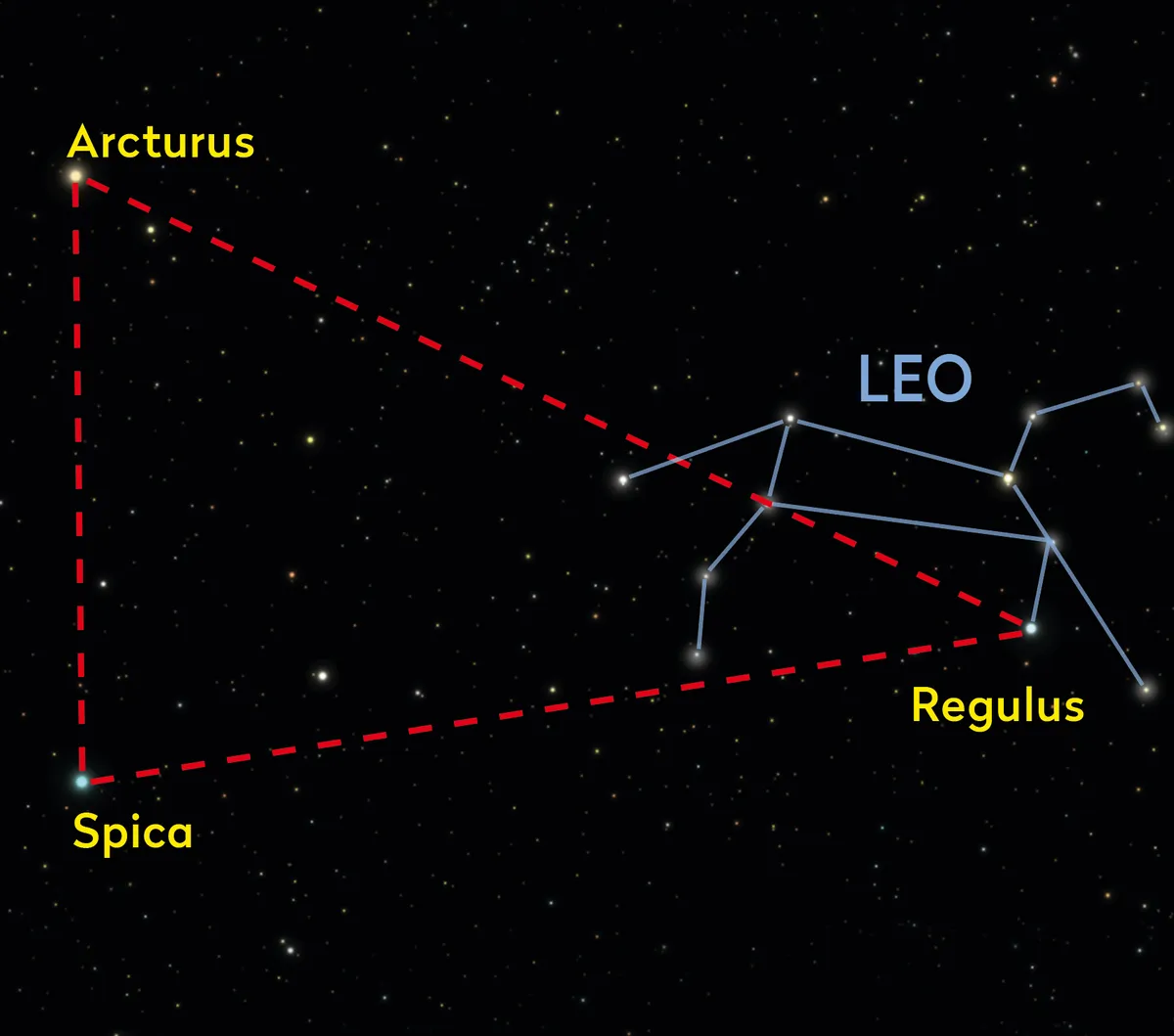

Spring Triangle

The under-appreciated Spring Triangle makes its way into the night sky in February, and by April it’s high enough to be a beautiful sight. Though the Triangle is broader than its summer cousin (see below), its corner stars Regulus (in Leo), Arcturus (in Boötes) and Spica (in Virgo) make this Triangle more understated.

Summer Triangle

The Summer Triangle of Deneb (brightest star in Cygnus, the Swan), Vega (in Lyra, the Harp) and Altair (in Aquila, the Eagle) appears late in spring. Imagine the two birds soaring overhead after a long summer sunset. Despite the name, the Summer Triangle can still be seen in January.

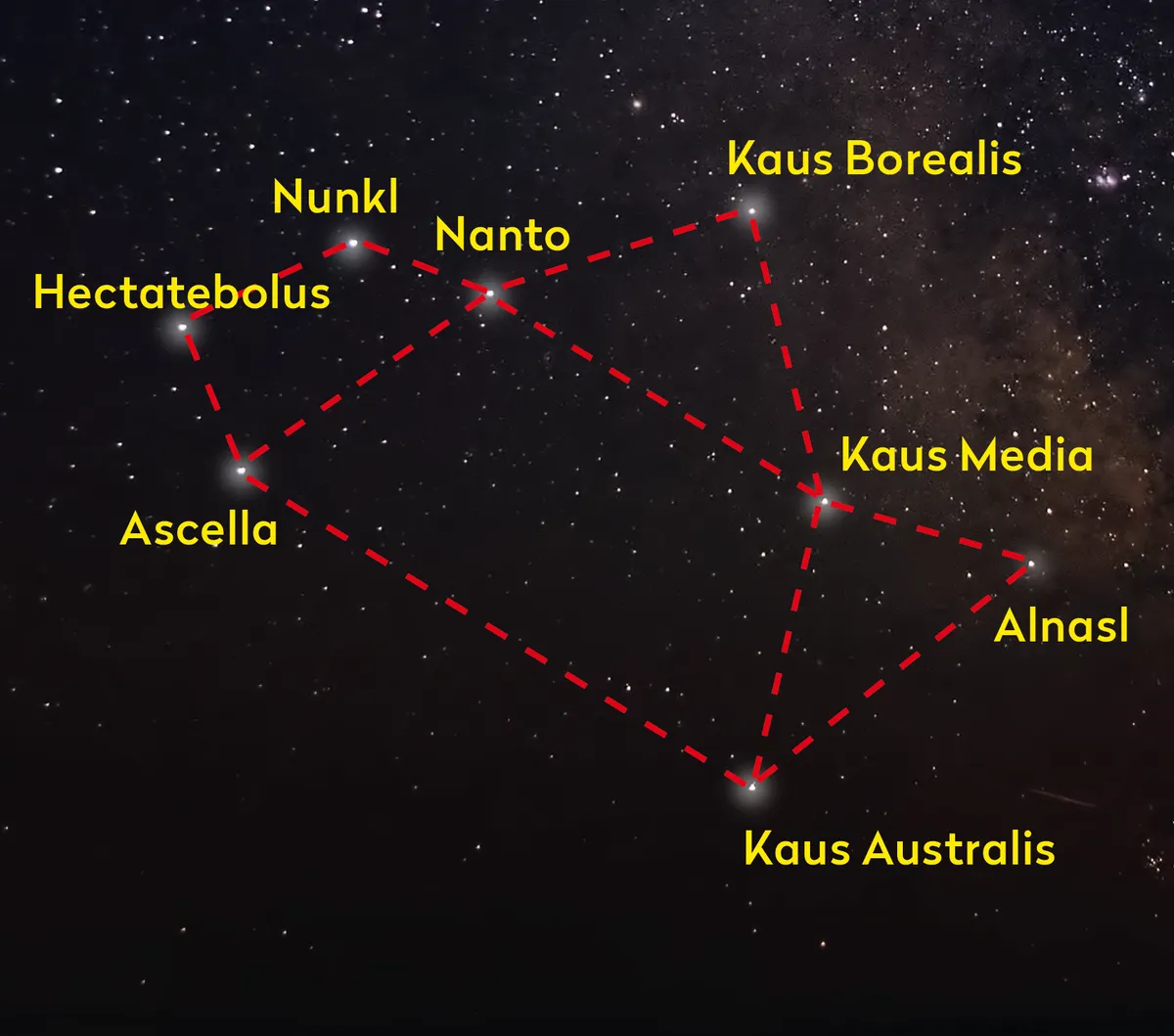

The Teapot

Sagittarius rides low in the southern sky all summer. Its brightest stars form a famous asterism that looks like a Teapot. If your skies cooperate, you may see what looks like a puff of steam billowing from the Teapot asterism’s spout. That’s the central part of the Milky Way; the light of countless far-off stars and dust blurred together.

What are your favourite asterisms? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.