The Perseid meteor shower is one of the best meteor showers of the year, under the right conditions, and a great summer stargazing event.

We are firmly in Perseid season, with the meteor shower's peak occurring this week, 12 August at 15:00 BST (14:00 UT).

This means the best time to see the Perseid meteor shower in 2024 is on the nights of 11/12 and 12/13 August, as these dates will produce the best rates.

The shower is active from late July through to late August, but the hourly rate is low for much of this period, only showing noticeable enhancement between 9/10 and 15/16 August.

These are the best nights to try for a Perseid.

Observing during the peak

The rise and fall from the peak rate of the Perseid meteor shower is typically quite sharp, over the course of several hours.

The night before the peak should show rates increasing as dawn approaches.

Rates naturally increase after local midnight (UT) and, with the radiant getting higher, the run-up to dawn on 12 August is optimum.

The following night, the post-midnight boost probably won’t be quite as impressive.

Moon phase for the Perseids in 2024

A key consideration when planning to observe a meteor shower is the time and phase of the Moon.

A bright, full Moon on the night of the peak will wash out all but the very brightest of meteors, whereas if the Moon is in its 'new' phase or is out of the way entirely, this will mean you see many more shooting stars.

The Moon is at first quarter on 12 August 2024.

This is a bright, early phase, but in August the early Moon phases tend to be poorly positioned, which works in our favour.

On the night of 12/13 August, the first quarter Moon sets around 22:50 BST (21:50 UT) before the sky gets properly dark.

Moonlight intrusion progressively worsens over the following nights, but even so, moonset is early enough to give you a good view up to 15/16 August.

The nights before the peak of the 2024 Perseid meteor shower are excellent, as the Moon won’t interfere at all.

The biggest issue will be the weather, so let’s keep our fingers crossed.

Get weekly Moon phases and times delivered directly to your inbox by signing up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter.

For more info on the year's displays, read our complete guide to meteor showers.

Perseids meteor shower explained

Perseid meteors occur when Earth passes through the dust spread around the orbit of short-period comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle.

The specific time of the peak represents when we are in the densest part of the dust stream.

The actual peak tends to show significant enhanced activity for a period of around 16 hours centred on that peak.

This is the width of the peak beyond which activity falls to less than half the actual peak value.

However, it’s not as simple as this, because activity appears naturally enhanced for the Perseids when the shower radiant (the point in the sky from which the meteors appear to emanate) in Perseus is higher in the sky and after midnight UT from the UK.

How to see a Perseid meteor

- Find a dark location away from stray light

- Make yourself comfortable (use a reclining chair to avoid neck cramp)

- Look at an altitude around 60° in any direction

- Looking northeast towards Perseus delivers shorter meteors that are easier to line up with the radiant

- Longest trails are visible at 90° to the radiant

- At 180° from the radiant, trails shorten, appearing to converge on the 'anti-radiant'

What causes the Perseid meteor shower?

Meteor showers occur when Earth passes through dust distributed around a comet’s orbit.

Entering our atmosphere on parallel paths, perspective causes meteor trails to appear to emanate from the same sky location, known as the shower radiant.

In the case of the Perseid meteor shower, the radiant is the constellation Perseus.

Over the activity period, the radiant’s position drifts against the background stars. Peak activity represents us passing through the densest part of the stream.

For more on the science of meteor showers, read our guide What causes a meteor shower?

Perseid meteor shower top tips

There are a few tricks and tips to employ when observing the Perseid meteor shower:

- Avoid artificial light as much as possible when viewing the shower

- Keep street and house lights out of your line of sight

- Use a torch with a red filter (to preserve your night vision) to find your way

- Let your eyes adapt to the darkness for 30-40 minutes and you’ll see much more

- Wrap up warm with good thermals and a warm, waterproof coat

- Keep your feet warm: cold can creep up through the ground even on a summer night

- Lie back so you see a large swathe of sky without straining your neck

- A garden lounger or other astronomy chair is a great viewing platform

- Look for Perseid meteors at an altitude around 60˚ in any direction

- Longest trails are seen 40–140˚ from the radiant; towards the radiant expect short trails.

- A look in the opposite direction to the radiant will reveal trails that appear short and converge to a point called the anti-radiant

Perseid displays often exhibit bright events, many of which show what appears to be an after image of the trail, which is a weakly glowing column of ionised gas.

This ‘meteor train’ fades from view as the energy in the ionised atoms is given up. High altitude winds may also affect the train, distorting its shape.

Zenithal Hourly Rate

If you read some of the media coverage of meteor showers like the Perseids, you might think that, at their peak, these events see a near-constant rain of bright shooting stars blazing across the sky.

Real meteor showers – while captivating and absolutely worth observing – are rarely like this.

One number that’s often mentioned is the Zenithal Hourly Rate, or ZHR.

This is a theoretical number of meteors that would be visible, on average, over an hour with the radiant of the shower at the zenith and the viewing occurring under perfect sky conditions.

The ZHR isn’t a good indicator of how many meteors you can expect to see every hour, however.

That figure will be lower because of things like light pollution and the typically lower radiant at the observing time.

You can estimate how many Perseids you might spot on average near the peak of the shower.

Such a calculation suggests that while observing at around 3am (BST) on the night of the peak, a group of observers at a suburban site – where the naked-eye limiting magnitude is, say, +5 – could potentially see a rate of about 25 Perseids an hour or so.

But the Moon should be taken into account, too.

What is a meteor?

Meteors begin their lives out in the depths of space as tiny grains of dust, known as ‘meteoroids’.

If any of these flecks of interplanetary material are unfortunate enough to hit Earth as they travel around the Sun, they collide with our atmosphere at many kilometres per second and get vaporised in the process.

The narrow ribbon of light that occurs when this happens is the meteor – what many call a ‘shooting star’ – and they’re happening all the time.

On a clear night if you look up at the stars for, say, half an hour or so, it’s highly likely that you’ll see a meteor at some point – especially from an observing site with dark skies.

Many meteors that you see like this will be what’s known as ‘sporadic’ meteors. Essentially that means that they are random in nature and can appear anywhere in the sky, going in any direction.

What’s different with the Perseid meteor shower is that Perseids, while they can materialise anywhere against the backdrop of stars, all appear to streak from a fairly-well defined point on the sky – astronomers call it the ‘radiant’.

This behaviour is, in fact, an optical illusion. The meteors are actually travelling on broadly parallel paths, as the meteoroids that create them plough into the top of Earth’s atmosphere.

It’s merely a trick of perspective that makes them look like they’re zooming across the sky from the radiant point.

'Normal’ sporadic meteors originate from meteoroids scattered in a fairly random way between the planets.

Meteors in meteor showers like the Perseids occur when Earth passes through a stream of dusty material left by a comet or asteroid as it journeys around the Sun.

In the case of the Perseids, that’s a cloud of dust left by Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle.

Every year Earth’s orbit brings our planet into a position where its path intersects with that trail.

How to photograph the Perseid meteor shower

A camera set up to do a multi-second exposure of the night sky will typically return a bright, overexposed frame if the Moon is nearby.

However, with careful tuning of the camera’s settings, it is possible to reduce the intensity of the recorded background sky so that it doesn’t overexpose.

For example, reducing the camera’s sensitivity (low ISO, small aperture) will deliver a multi-second exposure without overexposure.

Under normal nighttime conditions, such settings probably wouldn’t record many meteors.

To work here, the camera needs to be set to the settings you would normally use for meteor imaging – high ISO and wide aperture – but the exposure time needs to be reduced to prevent sky overexposure.

In this way, if a meteor trail passes through the camera frame, it should record just as it would if the sky were darker and the exposure longer.

There are caveats though. Shorter exposures mean more shots will be taken.

The ideal filetype here is your camera’s RAW image format, and such files tend to be on the large side.

Lots of large image files means you need plenty of storage available, but for modern cameras this shouldn’t be too much of an issue.

More frames also require more time to check afterwards.

Mind the gap in your imaging time

The use of RAW means that at the end of each shot a fair amount of data needs to be transferred to your camera’s storage card.

This can create a ‘gap’ in your camera’s imaging capability, a period when no image is being taken.

Under normal ‘dark sky’ meteor exposure settings, this gap will be far shorter than the exposure time.

However, when the Moon is about and exposure times need to be radically shortened, the gap becomes significant.

For example, a one-second gap vs a 29-second exposure means that only two seconds of imaging time is lost per minute (3.3%).

However, if the exposure time is reduced to one second, this equals the gap time. Consequently, 30 seconds are lost per minute of imaging time (50%).

A shorter exposure also raises the probability of truncating a meteor trail mid-flight, something that increases for brighter and longer meteor trails.

Although not ideal, it is still possible to set up a camera to record this year’s Perseid shower and, given clear weather, there’s every chance that you will be able to record some trails.

And as it’s likely there will be fewer people out having a go on the night of the 12th/13th, if you do capture a bright trail you may well be the only one to do so.

Follow our step-by-step guide below and see what you can catch.

For more advice, read our guide on how to photograph a meteor shower and our pick of the best equipment for photographing meteor showers.

Photograph the Perseid meteor shower, step-by-step

Equipment

- DSLR camera

- MILC camera

- Tripod or tracking mount

- Remote shutter release

Step 1

Choose a lens that will give you a good field of view but avoid going too wide as the trails will appear small and unimpressive. Something around the 14–18mm mark would be a good compromise. Have a set of charged batteries ready as well as plenty of storage cards and a lockable remote shutter cable.

Step 2

The camera will need to be mounted on a stable platform. A tripod will keep the camera still as the sky moves through the field of view. A tracking mount will keep the camera pointing at the same area of sky. If using a tracking mount, make sure the camera doesn’t end up pointing at a foreground object.

Step 3

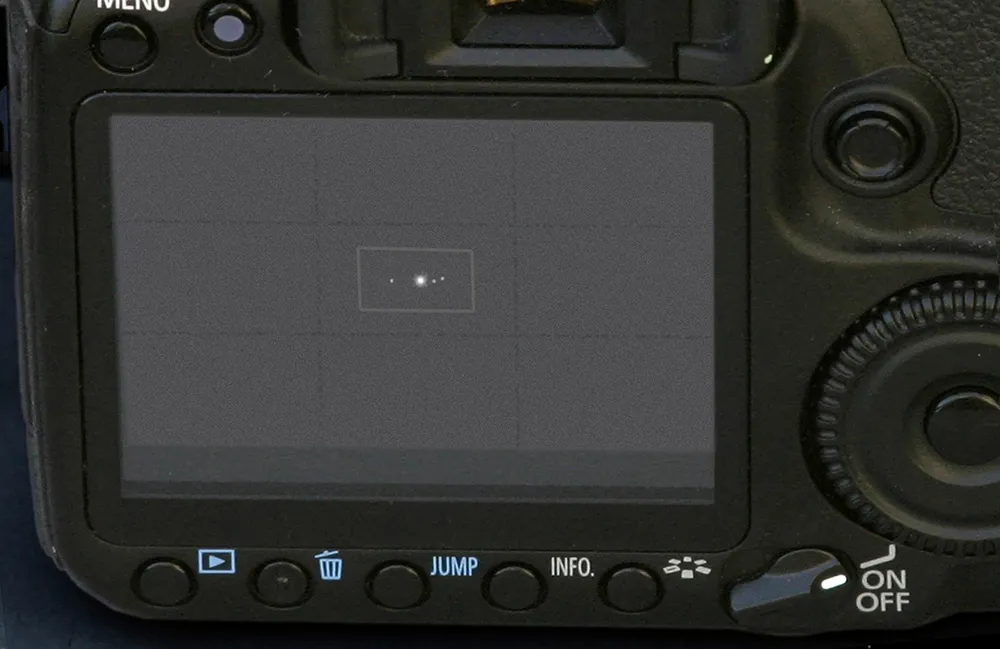

Set camera and lens to manual and check the camera clock. Pre-focus at infinity using a bright target such as Jupiter. Older cameras should be set to an ISO value of 3200 or 6400, while more modern bodies can go further, eg 5000-10,000. Fully open the aperture, reducing by a stop or two if edge stars distort.

Step 4

Aim at an area of sky that won’t bring the Moon into frame. Set a test exposure of 5s and take a shot. Examine the sky. If it’s overexposed, reduce the exposure. If it appears dark, consider increasing exposure. Reduce ISO or aperture only if you can’t get a non-overexposed sky with less than a 1s exposure.

Step 5

Set the camera to continuous shutter mode and lock the button down on a connected remote shutter cable. The camera should continuously take shots at the pre-set exposure. Routinely check the lens for moisture, using a 12V hairdryer to remove any. A 12V heater band is a recommended alternative if you have one.

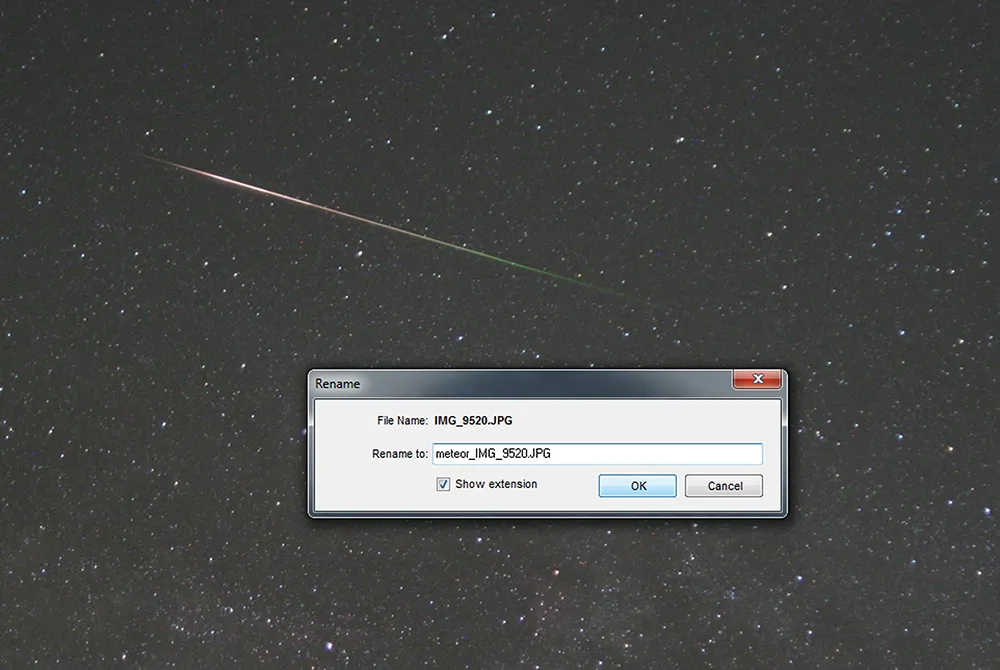

Step 6

Capture for as long as you can. Download the results. Using aviewing app, examine each image in turn. Renaming any suspected trail images with a prefix (eg ‘meteor_’) makes themeasier to find later on. Perseid trails should align with theradiant and often show green-pink coloration.

If you do manage to photograph a Perseid meteor, we'd love to see it! Find out how to send us your astrophotos, or get in touch via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.