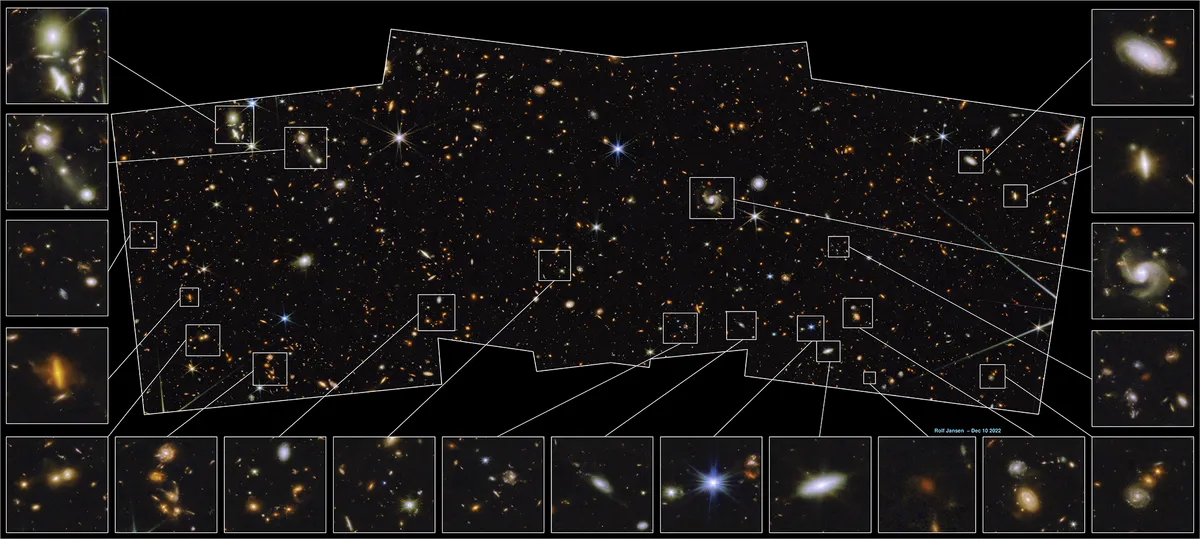

A year into what will hopefully be a 20-year mission, the James Webb Space Telescope has given us spectacular images of everything from Jupiter to the Orion Nebula.

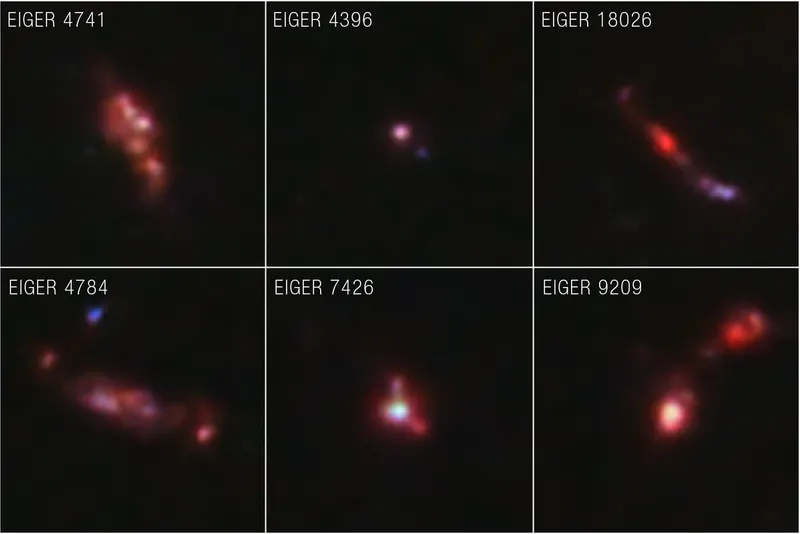

Yet the results that have attracted some of the most attention – images of what seem to be the most distant galaxies ever seen – are hardly spectacular.

Though it’s impressive that the light from each of these galaxies has been travelling towards us for more than 13 billion years, so that we see them as they were just as the Universe was getting started, the truth is that we see them as nothing more than faint blobs.

See the latest James Webb Space Telescope images

So what can we really know about a galaxy when all we have is a blurry, blobby image?

Obtaining spectra – where we measure out the intensity of light at various wavelengths – will help, not least because we can use features within this spectra to measure its redshift, and so determine how far away it is.

But what we really want to know is what these baby galaxies are like.

Have they formed stars, and when? Do they already host giant black holes?

Early results suggest that the galaxies may be much more developed than we expect, but a really interesting paper casts doubt on these headline results.

A team led by Desika Narayanan from the University of Florida, as well as astronomers in Edinburgh and Portsmouth, have been using powerful computer simulations to test the limits of our telescopes.

They're pointing a virtual JWST at synthetic galaxies to see what can be discovered.

Though the results are still being reviewed by a journal, the news is slightly alarming.

One of the most important things we want to know is the mass of all the stars that have formed in the few hundred million years between the Big Bang and the light we see today leaving the galaxy.

This is predicted by cosmology and gives us a sense of how the great project of assembling the massive systems, including galaxies like our own Milky Way, is going.

The trouble is, this paper shows that we are easily distracted if we happen to view the galaxy just as it

is experiencing a new burst of star formation.

Some of the stars created during the burst are massive.

These live fast and die young, so don’t persist long after the star formation has stopped.

However, during the burst, their bright light can outshine and wash out the background light from more long-standing members of the galactic population.

In other words, we might think we’re observing the main disc of the galaxy, but instead we’re only seeing fireworks of new stellar growth happening over the top.

This means that our estimate of their mass might be wrong by a factor of 10 or so.

The problem is worse for systems where stars form in bursts – something some expect in the early Universe.

This is an enormous error and threatens to derail our ability to test cosmology using deep JWST observations.

There is some hope. The authors suggest that more sophisticated models of how the star formation history of a galaxy relates to its spectra, perhaps developed with the help of machine learning, might be the solution.

But in the meantime, this is another reason to be careful in interpreting what JWST is seeing in the early Universe.

That’s okay though – we have a long mission ahead to figure these things out.

Chris Lintott was reading… Outshining by Recent Star Formation Prevents the Accurate Measurement of High-z Galaxy Stellar Masses by Desika Narayanan et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2306.10118.

This article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.