Moon rocks collected by the Apollo missions - and perhaps those collected by future lunar missions - could help investigate another of our Solar System’s key bodies: the Sun.A record of solar radiation could be locked away inside Moon rocks, giving scientists a glimpse into how the Sun has changed over time and its effect on the habitability of the inner planets.

The young Sun was much more volatile than it is today, but the question is: exactly how volatile? Many solar missions dedicated to the study of the Sun have collected data on this and other quandaries of solar science.

“We didn’t know what the Sun looked like in its first billion years,” says Prabal Saxena from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who led a new study of the lunar samples that were collected by Apollo astronauts and returned to Earth.

“It probably changed how quickly Mars lost its atmosphere, and it changed the atmospheric chemistry of Earth.”

Saxena’s team measured levels of sodium and potassium in Moon rocks collected on the Apollo missions.

Theories suggest both Earth and the Moon should be made of the same stuff, but these two elements are much rarer on the Moon than our own planet.

On the Moon, the solar radiation has stripped them away, as it has no atmosphere to offer protection.

Along with the Moon rocks, the team also analysed these chemical levels in lunar meteorites, to determine how active the infant Sun was.

As the activity of a star can affect a planet’s atmosphere – and therefore its habitability – the team wanted to make a comparison to other young stars.

While making this comparison directly is difficult, activity is linked to a star’s rotation rate, which is much easier to observe.

The team found the infant Sun rotated once every nine or 10 days, slower than at least half of today’s young stars (today the Sun takes 24 days to rotate).

However, this was still active enough to produce flares 10 times larger than the biggest in recorded history up to 10 times a day.

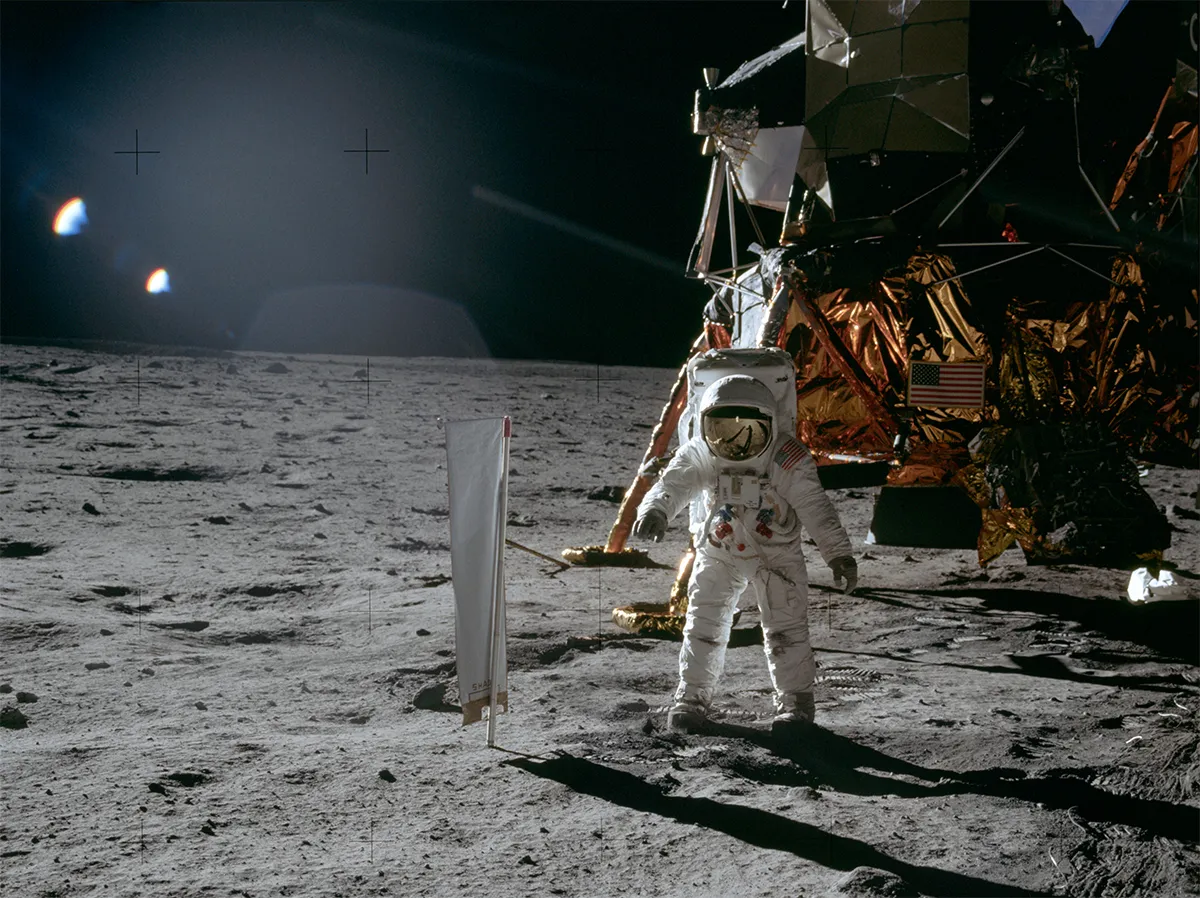

With no atmosphere to soak up the rays, the Moon has always been a great spot to study solar radiation – five of the Apollo missions deployed an experiment to capture solar-wind particles.

As more lunar missions are planned in the coming decade, the team hopes to learn more about not just the lunar surface, but the entire Solar System.