Astronomers have found a planet whose year lasts the same as a week on Earth, and which orbits so close to its host star, it's generating stellar flares that are scorching the planet's surface.

HIP 67522 b is a giant exoplanet – a planet orbiting a star beyond our Solar System – and is located 400 lightyears away.

More exoplanet science

That's incredibly close to Earth, in cosmic terms.

The key thing about HIP 67522 b is that it orbits extremely close to its star, which gives it some pretty odd properties.

Tight orbit, precarious position

HIP 67522 b's orbit around its host star is so tight that a year on the planet – the time it takes to go round the star once – is about the same length of time as one week on Earth.

And this tight orbit also means HIP 67522 b is dangerously close to its star, encouraging some pretty destructive behaviour from the star itself.

On Earth, we use the term 'space weather' to describe the effect of the Sun on our planet and other bodies of the Solar System.

This can include solar flares that erupt from the Sun and which can disrupt radio communications on Earth, damage satellites or even harm astronauts in space.

Luckily, Earth is far enough from the Sun – and we have a protective atmosphere – for space weather to not pose any direct threat to human life.

HIP 67522 b is not as lucky. It's is a gas giant planet, like Jupiter in our Solar System, and orbits a very young star.

For comparison, our Sun is about 4.6 billion years old, whereas star HIP 67522 is just 17 million years old.

And HIP 67522 is also a type of star that's known to flare, especially when it's young.

HIP 67522 b is causing its star to flare

Astronomers say HIP 67522 b and its star have formed a powerful, destructive bond.

While the exact science behind it is not yet fully understood, the planet is hooking into the star’s magnetic field, triggering flares on the star’s surface.

And these flares are firing energy back onto the planet.

Combined with further radiation coming from the star, this is causing HIP 67522 b to inflate rapidly, making it as big as Jupiter, despite having just 5% of Jupiter’s mass.

Astronomers say it's being blasted so much that in another 100 million years, HIP 67522 b could shrink and become a type of planet known as a 'hot Neptune'.

Or, if it loses a large amount of its atmosphere, a 'sub-Neptune'.

How to find a tight-orbiting planet

400 lightyears is a stone's throw in cosmic terms, but it's still too far away to capture images of flares hitting the planet.

A science team led by astronomer Ekaterina Ilin used space telescopes like NASA’s TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) and the European Space Agency’s CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExoPlanets Telescope), to track flares on the star and trace the planet’s orbit.

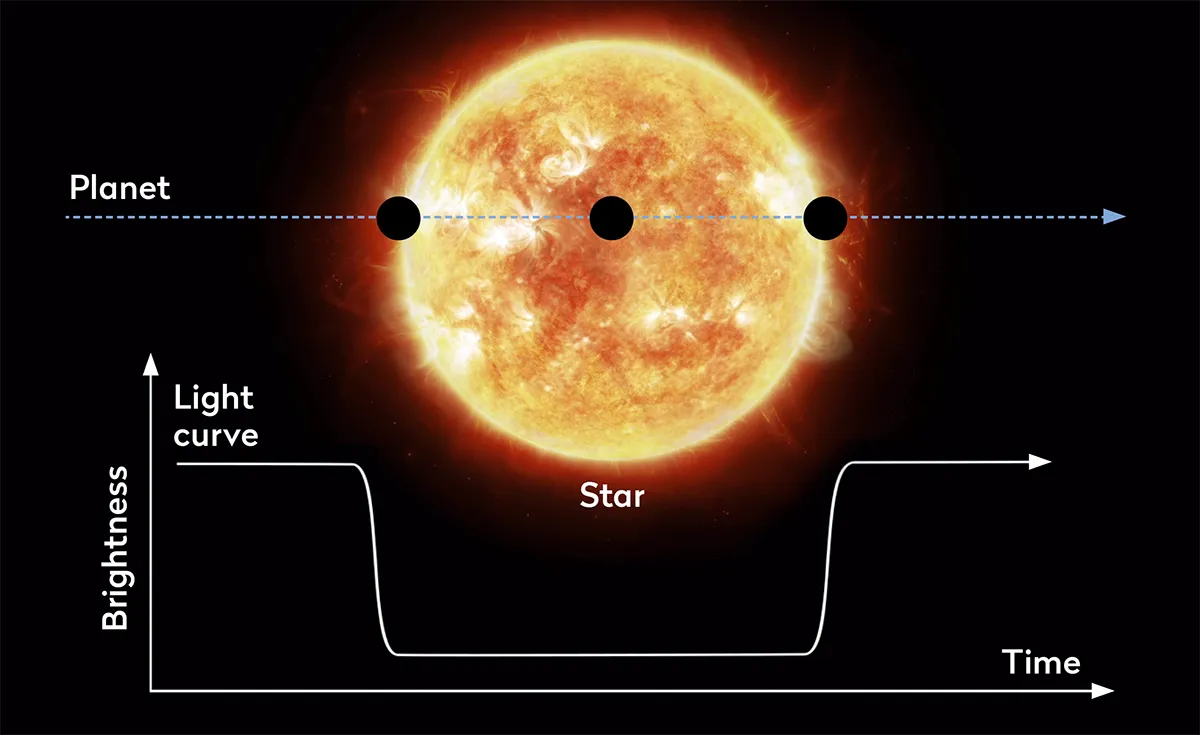

They used the transit method of exoplanet detection and study, which looks for dips in the brightness of a star's light that indicate a planet passing in front of that star.

As well as being a means of detecting an exoplanet in the first place, the transit method can also be used to learn more about the planet.

And the same method can also detect sudden bursts in brightness from the star: the stellar flares.

The team combined observations over five years and found HIP 67522 b is zapped with six times more flares than it would be without that magnetic connection.

So while planet Earth is the right type of planet and orbits just the right distance from its star for life to evolve comfortably, HIP 67522 b is proof that, for other planets, it's an entirely different story altogether.