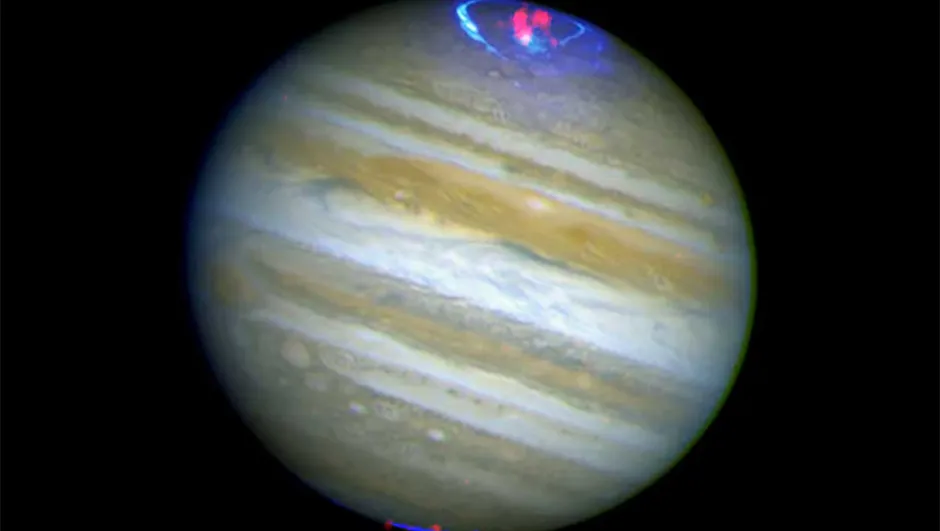

Jupiter’s northern and southern aurorae pulse differently and independently of one another, according to new research.

Like on Earth, Jupiter’s aurorae are caused by streams of charged particles from the Sun - known as solar winds - entering the planet’s upper atmosphere at its magnetic poles, hitting the gases present there and causing them to glow.

However, Jupiter’s aurorae are also generated by charged particles coming from Io, one of Jupiter’s main moons and home to many large, active volcanoes.

But while Earth’s southern and northern aurorae largely mirror each other in terms of activity, Jupiter’s are quite different.

At Jupiter’s south pole, high-energy X-ray emissions pulse every 11 minutes.

At the north pole, these emissions are more erratic, increasing and decreasing in brightness independently of the south pole.

“We didn’t expect to see Jupiter’s X-ray hot spots pulsing independently as we thought their activity would be coordinated through the planet’s magnetic field,” says lead author of the study William Dunn of the UK’s UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory.

To understand more about Jupiter’s aurorae, the team intend to combine information gathered by NASA's Juno spacecraft, currently orbiting the gas giant, with additional X-ray data captured by the XMM-Newton and Chandra X-ray observatories.

“If we can start to connect the X-ray signatures with the physical processes that produce them, then we can use those signatures to understand other bodies across the Universe such as brown dwarfs, exoplanets or maybe even neutron stars,” says Dunn.

“The behaviour of Jupiter’s X-ray hot spots raises important questions about what processes produce these auroras,” says study co-author Dr Licia Ray atLancaster University.

“We know that a combination of solar wind ions and ions of oxygen and sulphur, originally from volcanic explosions from Jupiter’s moon Io, are involved.

However, their relative importance in producing the X-ray emissions is unclear.”

One theory is that Jupiter’s aurorae form separately when the planet’s magnetic field interacts with the solar wind.

These magnetic field lines then vibrate, generating waves that transfer charged particles to Jupiter’s poles.

These change in speed and direction until they collide with Jupiter’s atmosphere, producing X-ray pulses.

Data from Chandra and XMM-Newton showed an ‘X-ray hotspot’ at each of the poles.

Each hotspot covers an area bigger than the surface of Earth, but the two have different characteristics.

“What I find particularly captivating in these observations, especially at the time when Juno is making measurements in situ, is the fact that we are able to see both of Jupiter's poles at once, a rare opportunity that last occurred ten years ago,” says co-author Professor Graziella Branduardi-Raymont from the Department of Space & Climate Physics at University College London.

“Comparing the behaviours at the two poles allows us to learn much more of the complex magnetic interactions going on in the planet's environment.”