A high-tech upgrade of one of the most powerful telescopes on Earth is giving astronomers the means to begin searching for the earliest-born stars in the history of the Universe.

The SOAR Telescope is located on Cerro Pachón in Chile and has received a major upgrade with the installation of the SOAR Telescope Echelle Spectrograph (STELES) instrument.

More amazing space science

Astronomers have already put it to the test by pointing it at one of the most amazing double stars in our Galaxy.

SOAR and Eta Carinae

STELES achieved first light – the astronomical term for the first time a new telescope is used – in August 2025.

Its target was binary star system Eta Carinae, along with 13 other targets.

Eta Carinae is not one, but two stars orbiting each other, and this binary pair has a history of brightening and dimming.

In fact, it underwent a huge explosion that was recorded in 1837, when it temporarily became one of the brightest objects in the night sky.

This event was known as the 'Great Eruption'.

Understandably, astronomers have kept a keen eye on Eta Carinae, on the off-chance that it might undergo a similarly spectacular event.

The larger of the two Eta Carinae stars is thought to be 90 times the mass of the Sun, while the smaller star is 30 times the mass of the Sun.

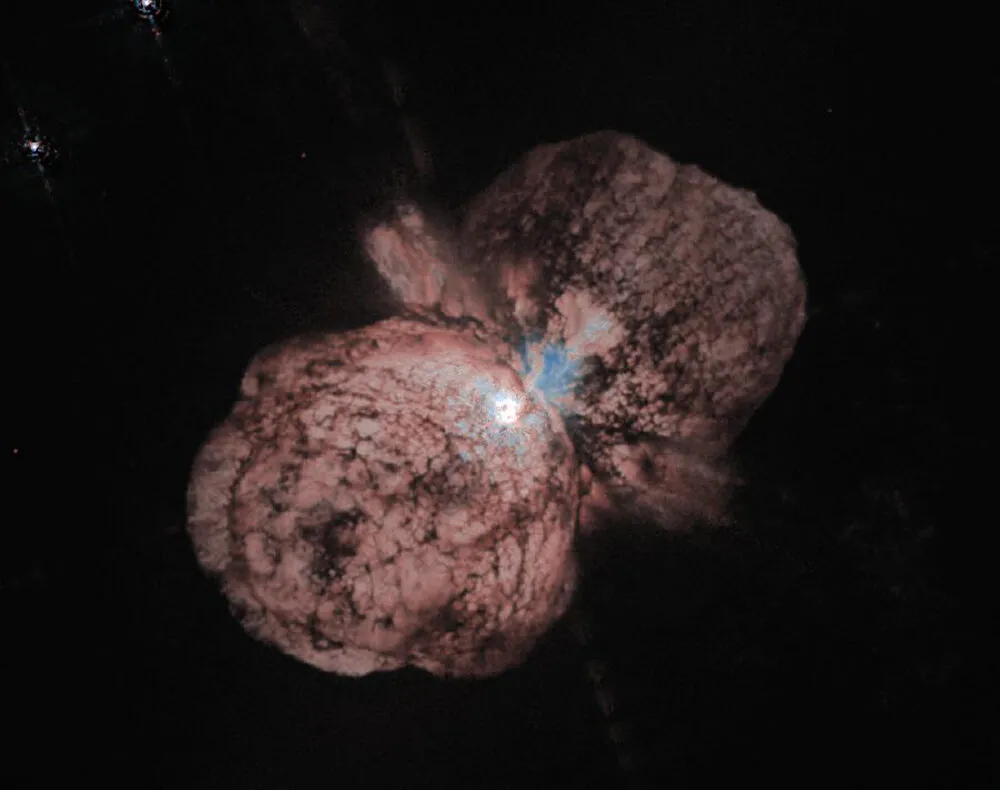

The whole system is more than five million times as bright as our Sun, but is obscured by the Homunculus Nebula, which is a cloud of material ejected from the larger star during the Great Eruption.

How STELES works

The STELES images of Eta Carinae can be seen here, and you may be wondering why it looks like a series of colourful lines, rather than what we might expect from an image of a star.

STELES divides light into two arms, one for short wavelengths of blue light (300–550 nanometers) and one for longer wavelengths of red light (530–890 nanometers).

Each section is then further separated into a spectrum of colours, and this spectrum of light can tell astronomers a lot about the object's composition, motion, rotation and even its distance from Earth.

Seeing the first stars

The STELES instrument's ability to gather a broad region of visible light in a single shot means it can quickly capture precise measurements of faint distant stars.

In fact, scientists say they'll be able to use it to study large numbers of metal-poor stars in and beyond our galaxy.

It will even search for Population III stars, which are the first generation of stars born, and currently exist only in theory.

These are the earliest born stars in the Universe and contain virtually no metals (an astronomical term for elements heavier than helium).

They've never been directly observed.

Scientists say STELES data could reveal the secrets of the chemical evolution of the Milky Way and unlock some of the mysteries of the early Universe.

It will begin searching for the Universe’s oldest stars in early 2026.

"STELES will undoubtedly enhance SOAR’s spectroscopic capabilities and will be a boon for researchers in the U.S. and Brazil," says NSF Program Director Chris Davis.

"STELES offers a unique combination of high spectral resolution and ultraviolet capability, making it a powerful tool for advancing our understanding of star and planet formation, the interstellar medium, and hot stars."