As 2020 marks the start of a new decade, it also marks a new era for space. In the coming years, both China and the US are taking their human spaceflight programmes to the next level, with both agencies setting their sights firmly on the Moon.

The ultimate goal for this human exploration is to send people to the surface of Mars in the 2030s. That’s not to say the Red Planet is being neglected until then.

A fleet of robotic explorers is being prepared to fly in 2020, ready to join the many spacecraft already at Mars and explore the planet for many years to come.

Read more about space missions:

- Looking back on the Rosetta mission at Comet 67P

- NASA rover to seek ice at the Moon's south pole

- A look at the NASA Artemis, SpaceX Crew Dragon and Virgin Galactic spacesuits

However, the road to the stars is not an easy one, particularly if you’re left stranded on Earth without a lift.

Both NASA and China’s heavy launch rockets – the Space Launch System (SLS) and the Long March 5 respectively – have been delayed for years.

The Long March 5 was taken off China’s launch roster in 2017, when one fell into the ocean shortly after launch.

Over in the US, the official line is that the SLS will be up and running by mid-2020, but several comments from NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine referring to a 2021 launch date have sowed doubt.

However, even without these two vehicles, 2020 is shaping up to be a pretty major year for humanity’s exploration of the Solar System.

Sending spacecraft to Mars

July 2020 sees an event that only occurs once every 26 months, the Mars launch window.

In 2020 an armada of spacecraft are planning on making the trip to the Red Planet.

NASA is planning on adding another mission to its long list of Mars explorers with the Mars 2020 rover.

However, rather than being a scientific mission in its own right, the rover will pave the way for future Martian exploration by both robots and humans.

The rover’s main task is to collect samples from across Mars’s surface.

But instead of analysing them in an onboard laboratory, the rover will create caches for a future mission to collect and bring back to Earth.This return mission is currently being planned by both NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA).

The Mars 2020 rover will also carry several technology demonstration experiments.

One of these, the Mars OXygen In-situ resource utilization Experiment (MOXIE), will suck carbon dioxide in from the Martian air, then split it apart to create oxygen.

The technology could one day be used to create rocket fuel and breathable air.

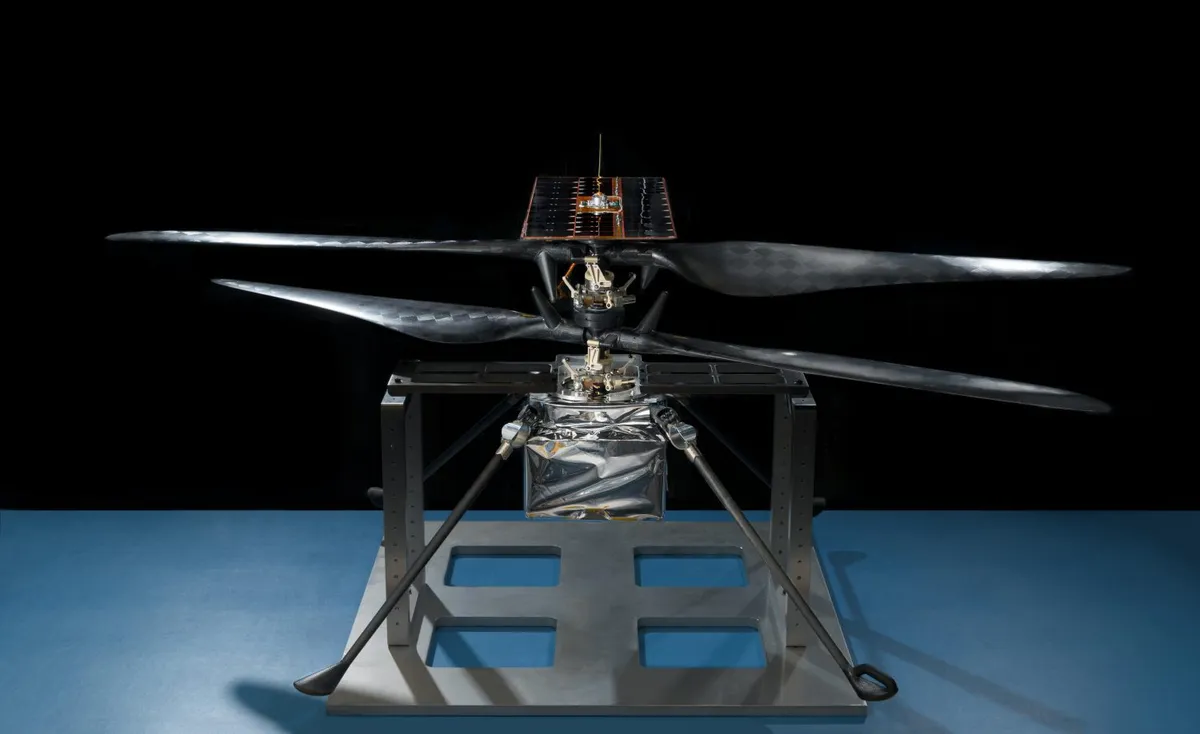

Finally, the rover will carry the Mars Helicopter Scout, a drone-like probe that flies through the thin Martian atmosphere, reaching parts of the planet that rovers cannot.

Searching for signs of life on Mars

Joining NASA’s rover will be the second half of ESA’s ExoMars mission – the Rosalind Franklin rover.

“The main goal of the mission is to find evidence of past or present life,” says Pietro Baglioni, the rover manager.

However, as cosmic radiation has likely irradiated any life signs near the surface, the rover will have to dig in.

“ExoMars will be the first rover equipped with a drill capable of penetrating to 2m, where there is more chance of finding something scientifically interesting.”

While the rover is ready, the landing system is not. When the first half of ExoMars – the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) – arrived at Mars in 2017, it dropped off a test lander, Schiaparelli, only for it to crash.

While the cause of Schiaparelli’s demise has been fixed, there are still other issues with the 2020 lander.

“We have experienced difficulties with the qualification of the parachute systems of the descent module,” says Baglioni.“There are tests at the beginning of 2020 that will tell us whether we can fly or not.”

If the answer is ‘not’, then the lander will be put into storage until the 2022 launch window.

Joining these two will be a Chinese rover. Not much is known about the mission – China is secretive about its space efforts – but the nation has made no effort to hide the fact that it wishes to explore Mars.

The rover will travel alongside an orbiter, and together they will study the planet’s geology and atmosphere.

Things seem on track, but the launch requires a Long March 5 rocket. Any delay with the launch vehicle could leave the rover with a 26-month wait.

Finally, the United Arab Emirates aims to launch its Hope orbiter, which will study Mars’s atmosphere.

The UAE Space Agency was only set up in 2014, and Hope is their first planetary space mission – a first step of an ambitious plan to build a colony on Mars by 2117.

Mars is already a busy place, with the Curiosity rover and several orbiters currently exploring the planet, but things will only get busier when the latest wave of Martian invaders arrives in 2021.

Missions to investigate the Sun

Two solar spacecraft will soon begetting to know our star’s atmosphere.

In February 2020 ESA will launch the Solar Orbiter spacecraft.

“The mission will explore the Sun and its connection to the plasma bubble that surrounds the Solar System we call the heliosphere,” says Daniel Müller, project scientist on Solar Orbiter.

“The key to understanding this lies in the polar regions of the Sun, which can’t be seen from the ecliptic. We will fly a trajectory that gradually raises the orbital plane to get a good view of the poles.”

The spacecraft’s orbit will pass just 0.28 times the Earth-Sun distance (42 million km) away from the solar surface, before swinging out towards Venus.

Meanwhile, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is planning another solar mission, Aditya, which is currently due to fly in April.

The spacecraft will look at the Sun’s corona, as well as its ultraviolet radiation and the solar wind, both of which have an effect on Earth’s climate and atmosphere.

Asteroid sample return missions

There’s only so much scientific equipment you can put on a spacecraft. To really get to know a space rock, you have to bring a piece back to Earth.

Two asteroid-investigating spacecraft are already hard at work. The first, Japan’s Hayabusa2, arrived at asteroid Ryugu in June 2018.

The spacecraft has already taken two rock samples and is due to arrived back at Earth in December 2020.

Once safely recovered, its cosmic cargo will be sent off to the world’s premier laboratories for close study.

Meanwhile, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx is taking its time at asteroid Bennu. OSIRIS-REx has been mapping the asteroid since December 2018 to find the perfect landing spot.

In mid-2020 it will touch down then harvest dust by blasting the surface with nitrogen gas.

The spacecraft is due to leave Bennu in March 2021, reaching Earth in 2023.

Meanwhile, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) is planning to launch its own sample return mission in 2020, this time to the Moon.

The Chang’e 5 lander aims to return around 2kg of lunar material from up to 2m underground.

However, launch is reliant on the uncertain future of the Long March 5 rocket.

Human spaceflight in 2020

The next decade is shaping up to be a landmark era for human space travel with missions to the Moon, space tourism flights and a new space station all set to start operations in the next 10 years.

In 2020, both SpaceX and Boeing are set to carry their first crew to the ISS as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Development programme.

The project was set up in 2010 after the cancellation of the Space Shuttle, commissioning private companies to build and operate crew-capable spacecraft to and from the ISS.

The first crewed test flight, each lasting only a few days, of both SpaceX’s Crew Dragon and Boeing’s Starliner are due to happen in the first quarter of 2020.

As long as these flights don’t show up any problems, the spacecraft will be then pressed into full operation in the following months.

Elsewhere in the private sector, on 28 September 2019 SpaceX CEO Elon Musk announced that the first prototype of his new space vehicle Starship – a reusable spacecraft that will become SpaceX’s main vehicle – will have its first test flight in early 2020, with potential crewed flights later in the year.

Meanwhile, 2020 could be the year space tourism finally takes off, with both Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin tentatively stating they hope to start flying passengers by the end of the year.

Return to the Moon

With private enterprise taking over low-Earth orbit, NASA itself is concentrating on getting humans further out into the Solar System, starting with the Moon.

The first test phase of this project, Artemis-1, is currently slated for a mid-2020 launch and will involve the first uncrewed test flight of NASA’s crew capsule, Orion.

The plan is to fly Orion around the Moon and back, but the mission requires the use of the SLS, which may not be ready in time.

Another human spaceflight mission that might be left on the ground awaiting a ride is the Chinese space station.

The nation had hoped to use the ISS as a launchpad for sending its own taikonauts (Chinese for astronauts) towards the Moon and beyond, but a 2011 US law bans the two nations from working together, forcing China to work on its own space station.

The first module of a permanent orbital facility is now due to fly in mid-2020, provided the Long March 5 is ready to carry it.

Russian developments

One mission that might get off the ground, however, is the latest expansion to the ISS from the Russian space agency, Roscosmos.

The new module – a joint research hub, sleeping quarters and storage space known as the Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM) or Nauka – has been planned since before the main station even flew.

However, its construction has been beset with problems. In 2014, its exterior plumbing had to be replaced following a leak, then three years later metal dust was found in the fuel tanks meaning they also needed to be changed.

Now all fixed up, Nauka is scheduled to fly to the ISS in June 2020.

Elsewhere in the world, India is on the way to becoming the fourth nation capable of launching humans into space.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (IRSO) is in the final stages of developing its Gaganyaan crewed capsules, with the first uncrewed test flights due at the end of 2020.

Elizabeth Pearson is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's news editor. This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.