Since it was founded in May 2025, the European Space Agency has brought together European countries for sustainable and collaborative space exploration, launching missions like the Cassini–Huygens probe in 1997, which ranged as far as the rings of Saturn.

ESA emerged from the need for a multinational European space programme, particularly to compete with the strength of research being produced by the USA and Soviet Union after World War Two.

The organisation can trace its roots back to two separate European space agencies set up in the 1960s: the European Launch Development Organisation (ELDO), which sought to develop a launch system; and the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO), which focused on developing spacecraft.

In 1975, ELDO and ESRO were merged into what is now the European Space Agency, composed then of just 10 member states.

Since its formation, ESA missions have shaped our understanding of space and advanced the technology we use for astronomy.

Its first mission, Cos-B, which launched in 1975 and aimed to study gamma radiation emitted from astronomical objects, operated for four years longer than planned.

Only a handful of gamma-ray sources were known before Cos-B.

ESA’s Integral, launched in 2002, has now taken up its mantle, investigating gamma-ray bursts by detecting not only gamma rays, but X-rays and visible light.

Today, the European Space Agency aims to provide cooperation in space research among European states in a peaceful way, with the view of using research and technology for scientific purposes and space operations.

It consists of 23 member states and has over 2,500 employees across its nine sites.

Over its last 50 years, it has demonstrated science that has captured the imagination of people across the world, providing infrastructure for researchers and citizens, as well as shedding light on some of the Universe’s most challenging problems.

ESA’s missions have spanned our Solar System, looked into the early Universe, and kept an eye on Earth.

It works closely with NASA and with other international astronomical organisations, like the European Southern Observatory.

Its projects are numerous and many of them have household acclaim. Here are some of its biggest achievements in the last half-century.

Ariane: a rocket for Europe

One of the European Space Agency's biggest contributions to the space sector has been the development of the Ariane satellite-launcher programme.

Started in 1979, Ariane aimed to enable Europe to have independent access to space.

The small satellite launchers that were used in Europe prior to Ariane, such as Diamant A and B, were successful but not suitable for large payloads.

Europe needed a larger, more flexible launch system.

One of ESA’s precursors, ELDO, was developing a satellite launcher called Europa, which relied on elements from different European nations – the UK, Germany and France.

The project was plagued with technical failures. An ELDO rocket was ‘successfully’ launched in 1964, but became highly unstable at around two minutes into its flight and eventually broke up.

By 1973, the European rocket programme had been shelved.

In the wake of these failures, France proposed the Ariane project as a replacement for Europa, under the guise of L3S (an abbreviation of the French for third-generation substitution launcher).

Ariane-1 had a dramatic start at its first attempt on 15 December 1979, with the rocket motor abruptly going out.

It launched successfully nine days later from Kourou, French Guiana on 24 December 1979.

While Ariane-1’s purpose was to send satellites into geosynchronous orbit, it was particularly important because of its capability to send a pair of satellites on a single launcher, reducing costs.

The Ariane series of rockets has had a significant impact on European spaceflight, launching satellites such as Giotto, ESA’s first deep-space mission to Halley’s Comet; Envisat, an Earth-observing satellite that was the largest of its kind at the time; and Rosetta, the comet-chaser.

Its most recent iteration, Ariane 6, was successfully launched in 2024.

Journey to the surface of Titan

A mission that captured the hearts of many, and perhaps one of the European Space Agency's most spectacular, Cassini–Huygens took a space probe all the way to Saturn.

The craft was composed of both NASA’s Cassini space probe and ESA’s Huygens lander, which eventually landed on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon.

To date, it remains the furthest landing from Earth ever made.

Launched in 1997, Cassini–Huygens reached Saturn in 2004, where it remained until 2017.

In the 1990s, the joint NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope had spotted an unusual patch on Titan’s surface.

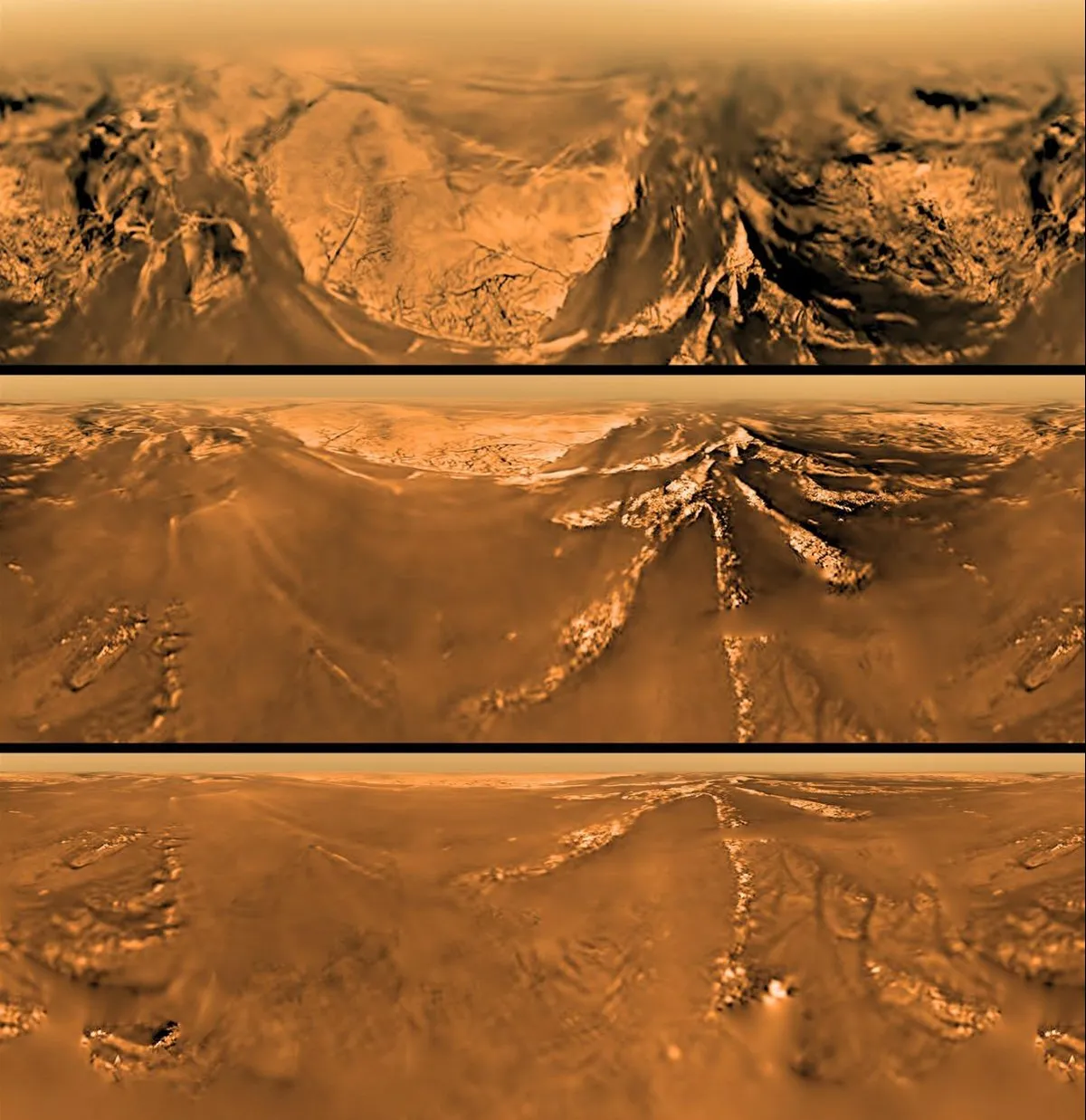

Both Cassini and Huygens were able to solve the mystery of this feature as they observed Titan both from afar and up close, taking multiple pictures from orbit and during Huygens’ landing on the moon.

The probe’s descent took two and a half hours under parachute and eventually revealed the features similar to rivers and seas we have on Earth.

Unlike our planet, however, these features were caused by liquid ethane and methane.

Extraordinarily, Huygens transmitted its information to Cassini, which was still in orbit around Saturn.

This data was relayed home, but an error meant that only half of Huygens’ data was recorded.

The invaluable half that was received has been instrumental in our understanding of Saturn and laid the foundation for NASA’s Dragonfly mission, proposed to launch in 2028, which will return to the surface of Titan, this time with a robotic rotorcraft.

Comet-chasers

In 2004, the European Space Agency launched Rosetta, an ambitious comet-hunting mission, to track down and land on the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko during the two-year period when it was closest to the Sun in its orbit.

Rosetta consisted of an orbiter, a lander called Philae and over 20 scientific instruments.

To intercept Churyumov–Gerasimenko, the probe had to receive numerous assists from Earth’s gravity, enter a period of deep-space hibernation and then perform a series of complex rendezvous manoeuvres.

Ten years after its launch, in August 2014, Rosetta caught up to Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

A few months later, in November, it deployed the Philae lander to the comet’s surface, the first-ever landing on a comet.

It was a myriad of firsts: the first comet rendezvous, the first tracking of a comet on its orbit around the Sun and the first landing on a comet’s surface.

Philae’s battery ran down just two days after landing on the comet, but before its loss of power it was able to detect the presence of organic compounds, the building blocks for life, in the comet’s atmosphere.

Comets can act like time capsules, and measurements from the surface of Churyumov–Gerasimenko have shed light on the history of our Solar System.

While Philae briefly gained power again in June 2015, Rosetta’s communications with the lander were turned off in July 2016.

Rosetta’s impressive tour of the Solar System ended in a controlled hard landing on Churyumov–Gerasimenko in September 2016.

Laboratories of the sky

Europe’s largest contribution to the International Space Station is its Columbus module, a science laboratory.

It was delivered by NASA’s STS-122 mission in 2008 and ever since has functioned as a laboratory for multidisciplinary research under microgravity.

At around 7 metres (23ft) long and 4.5 metres (15ft) wide, Columbus also houses four platforms on its outer wall to which experiments can be attached.

This means researchers can expose their experiments directly to outer space and its hostile conditions: vacuum, powerful radiation, microgravity and temperatures approaching absolute zero.

Hundreds of experiments have been undertaken on Columbus, enabling studies of quantum physics, the effects of reduced gravity on the human body and the viability of living cells in space transit.

Columbus’s outdoor platforms were used to house bacteria, lichen, algae and even seeds for 18 months without protection.

Upon returning to Earth in 2009, the lichen awoke from dormancy, suggesting that life could possibly survive in the harsh environment of space, perhaps on the back of an asteroid ready to deposit it on a planet like Earth.

Webb and Hubble

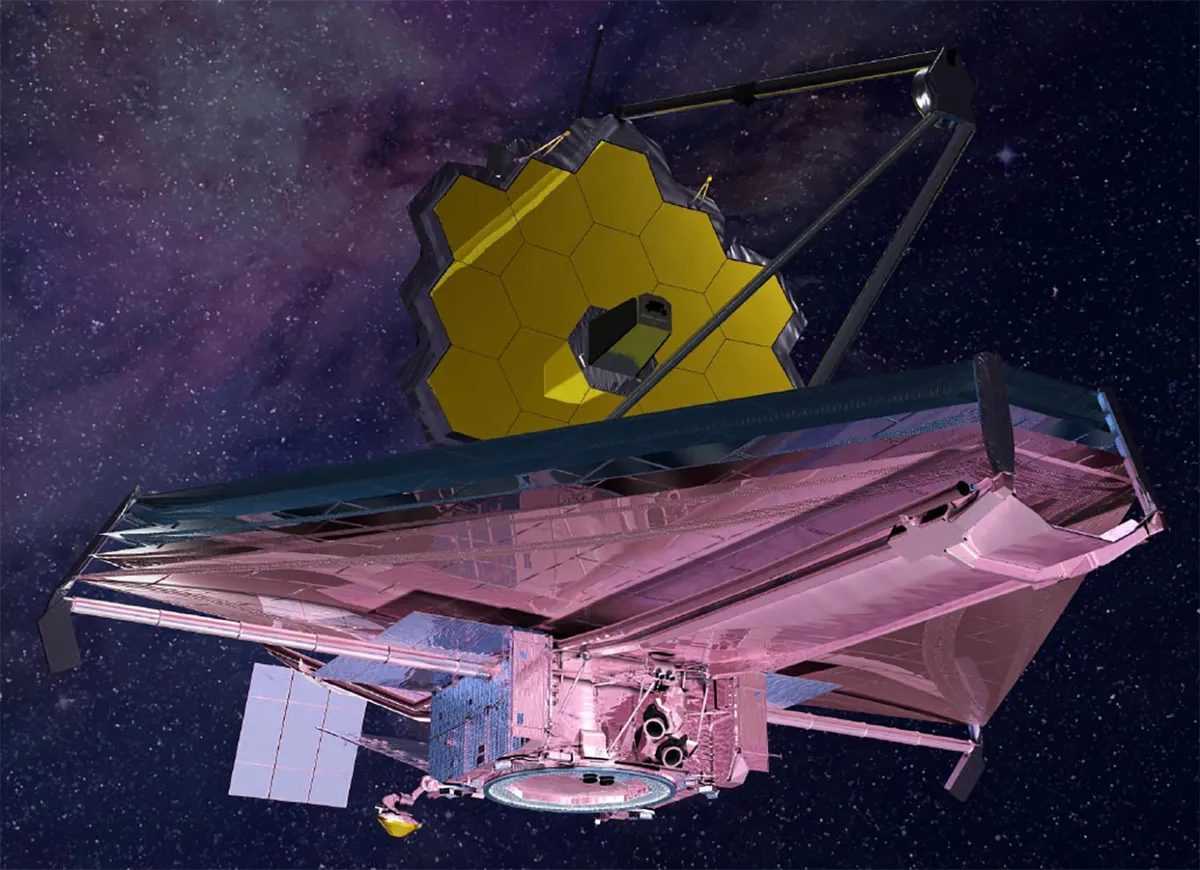

In December 2021, the European Space Agency launched the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in collaboration with NASA.

Since then, the JWST has been instrumental in furthering our understanding of the early Universe,

galaxy formation and exoplanets.

JWST has been a feat of engineering, with a primary mirror composed of 18 honeycomb-like segments, amounting to an overall diameter of 6.5 metres (21ft).

JWST’s primary mirror was so large it had to be folded for launch and deployed in space.

The observatory operates in the infrared, complementing the data received from the Hubble Space Telescope, launched in a partnership between NASA and ESA in 1990.

Both Hubble and JWST have pushed the frontiers of human vision, enabling us to look further and further back into the history of the Universe and to answer questions that were previously beyond our comprehension.

They have also produced some of the most iconic images of space in our lexicon, such as the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, a view of nearly 10,000 galaxies in a small patch of sky; and Webb’s view of the Pillars of Creation, a star-forming region within the Eagle Nebula, 6,500 lightyears away.

What next for the European Space Agency?

ESA has been a mainstay of global astronomy for the last half a century.

European Space Agency technology, laboratories and scientists have moulded the landscape of space exploration, and ESA missions continue to push the frontiers of space travel.

In the coming handful of years, its missions will continue to flourish.

The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) – launched in 2023 – will reach the gas giant by 2031.

The Lunar Gateway, the first international space station to orbit the Moon, is now under construction.

Programmes like the Rosalind Franklin rover, set to launch in 2028, will soon tell us about the possibility of life on Mars.

ESA’s longer-term future also looks bright, with projects being designed to answer big questions about the nature of the Universe.

Future European Space Agency missions

The European Space Agency has announced a diverse range of future missions for its next half-century.

These fall under two strategic science programmes: Cosmic Vision, ESA’s current planning cycle that will run missions until 2035; and large-class missions for 2035–2050 that fall under the Voyage 2050 planning cycle.

Cosmic Vision

This programme asks four major science questions:

- What are the conditions for planet formation and the emergence of life?

- How does the Solar System work?

- What are the fundamental physical laws of the Universe?

- How did the Universe originate and what is it made of?

Voyage 2050

This programme will turn its focus to three themes:

- Moons of the giant planets, which will build on the Cassini–Huygens Saturn mission and the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) mission, to investigate the habitability of worlds in our Solar System.

- From temperate exoplanets to the Milky Way, it will investigate the ecosystem of our Milky Way, using our local Galaxy as a laboratory for understanding galaxies in general.

- New physical probes of the early Universe, to look at outstanding questions in fundamental physics and astrophysics, and phenomena like gravitational waves or the cosmic microwave background to better understand big questions such as how the Universe began.

2026: PLATO

Planetary Transits and Oscillations of stars, an exoplanet-hunter that will look for worlds in the habitable zone of Sun-like stars, as well as measuring exoplanet size, discovering exomoons and searching for rings around them.

2029: ARIEL

Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey will examine the atmospheres of 1,000 planets in our Galaxy from a vantage point at Lagrange Point 2.

2035: LISA

Laser Interferometer Space Antenna is an instrument formed by three spacecraft, designed for sensitively detecting gravitational waves.

2037: NewAthena

New Advanced Telescope for High-Energy Astrophysics, an X-ray observatory for mapping hot clouds of gas, such as around black holes.

This article appeared in the May 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine