While much of the credit for saving the Apollo 13 mission went to the astronauts on board, the rescue of those three human lives was the result of thousands of people working around the clock to bring the crew home safely.

Jerry Woodfill was an engineer for the mission and working on the ground at NASA when the call came down: "Houston, we've had a problem."

We spoke to Woodfill to find out what it was like being in the midst of the action on that fateful day.

I had a role as the alarm system engineer for the Apollo programme for the whole Apollo programme. I was assigned the command module alarm system shortly after coming to work at NASA in 1965.

When the guy doing the alarm system on the lunar lander left NASA a few months later, they said "well Jerry’s already got the command module so let's assign him the lunar lander alarm system," so I had both.

I was never an astronaut. I wasn’t a flight controller, but I was an engineer I was the guy that knew how the system worked.

At first, the engineers did not have that big a role with regards to mission operations. But in 1967 we were working on Spacecraft 12, which went on to be Apollo 1.

On 27 January 1967, it was a Friday evening, they were testing the spacecraft. Something happened with the environmental control system, there was a short circuit.

There were all kinds of flammable materials onboard and a pure oxygen atmosphere. That’s a horrible situation – flammable materials, a spark and pure oxygen. There was a huge fire, a tragedy that killed the Apollo 1 crew.

It was 8 minutes after 9pm and I was watching the console. That’s when I heard in my headset: Houston, we’ve had a problem.

My concern was why had there been a problem in my alarm system, had we been able to save their lives.

We reviewed everything, and there’s no way my alarms could have saved them. Over the years I’ve always wondered if I’d done a better job could we have saved them. We’ve all wondered that.

The Apollo 1 incident resulted in the formation of the Mission Evaluation Room (MER) – a group of engineers who had been involved in designing and testing the systems. If anything happened during the mission you could go to these guys who were monitoring everything.

We were kind of like flight controllers but in another room not too far from the Missions Operations control room.

We were the backup guys, listening along on our headsets, watching over the shoulders of the astronauts and the flight controllers. And I was the guy responsible for the alarm system.

So I was in that room when Neil Armstrong was landing on the Moon and alarms began to ring, and I was there when Apollo 13 exploded.

The Apollo 13 explosion

On 13 April 1970 while Apollo 13 were on their way to the Moon I had my headset on. It was 8 minutes after 9pm and I was watching the console.

Then, all at once, it flickered off and on, like a TV set. That’s when I heard in my headset, “Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

What had happened was an oxygen tank in the service model, Tank 2, had actually exploded.

But the thing was that when it exploded it turned on some of my alarms. The explosion took down the power and caused one of the astronauts to say “We’ve had a Main Bus B Undervolt.”

Now that got my attention.

When I heard that call and saw the screen flicker I thought "Oh no! It’s my system that’s caused the problem."

There were 5 or 6 alarm lights turning on and I thought it couldn’t be that bad, it’s gotta be my system.

Then Jim Lovell said, “we see something venting.” That means there’s a real problem, it’s not an error in my system. We’re going to have to work to rescue these guys.

We still have that challenge right now as we talk about going back to the Moon with Artemis. I like this new goal of getting back to the Moon in four or five years because I’ll still be here!

For the next 4 days I and the mission's operations team, led by Gene Krantz and 3 other flight controllers on their shifts, worked to come up with solutions to all those grave problems that likely should have killed those 3 guys.

One of the problems that you’ve probably seen in the movie Apollo 13 (see our guide to the best space movies of all time) was making the lunar lander, which is designed for 2 men for 2 days, last for 4 days with 3 guys to get back to Earth.

There weren’t enough filters to take the carbon dioxide out of the cabin atmosphere and so my alarm system turned on the CO2 Partial Pressure Alarm.

Those three guys had 24 square filters from the mothership but the lunar lander had a system that required round filters. How do you make them fit?

In the Mission Evaluation Room there were around 70 engineers, not just NASA engineers but contractors, all intimately knowledgable about every system.

They knew the things that were going to be on board and jury-rigged a system that would make a square filter fit a round hole.

There’s a hose they have to circulate cabin atmosphere into an astronaut’s suit before he goes onto the lunar surface.

They could use that hose with a plastic bag that has the square filter at the mouth of it. We could pump atmosphere into that bag and it would be filtered.

Power problems

The problem was the oxygen tank provided electrical power to keep the command ship alive. But when the explosion happened that power was lost.

The Command Module has emergency batteries, but they’re only to be used when you approach re-entry. They’re charged through the main power system.

The power from that wasn’t going to be available because the fuel source of that power was the oxygen from the exploded tanks.

They used electrical power for many things, including navigation needed to find the way back to Earth. The plan was to transfer over to the lunar lander – which had some power – but its computer didn’t have the knowledge of where they were in space.

I’ve been at the Johnson Spaceflight Center for 54 years, I’m number seven in longevity. I’m one of the only ones who can tell these stories because I was there when it happened.

They had to use those emergency batteries to transfer over navigation information to the lunar lander computer. They didn’t have a choice, but when they finished they realised they’d depleted the emergency batteries.

Here was another challenge for the Mission Evaluation Room. The Electrical Power Manager was a man named Art Campus. Art had gone to see a movie called ‘Marooned’.

In the movie there's a situation where they face similar things that they faced in Apollo 13 and there’s a scene where they charge their batteries and Art started thinking "how would you do that?"

So when he got a call from the Space Center after the Apollo 13 explosion he writes down the procedure. That’s one of the things that saved the lives of the Apollo 13 crew.

If you listen back to the audio you can hear people talking over one another because there were so many people trying to understand a big job and there were lives in the balance.

It was confusing but we’d run all these things through simulations so this wasn’t the first time. There was always a backup procedure and a plan.

Home safely

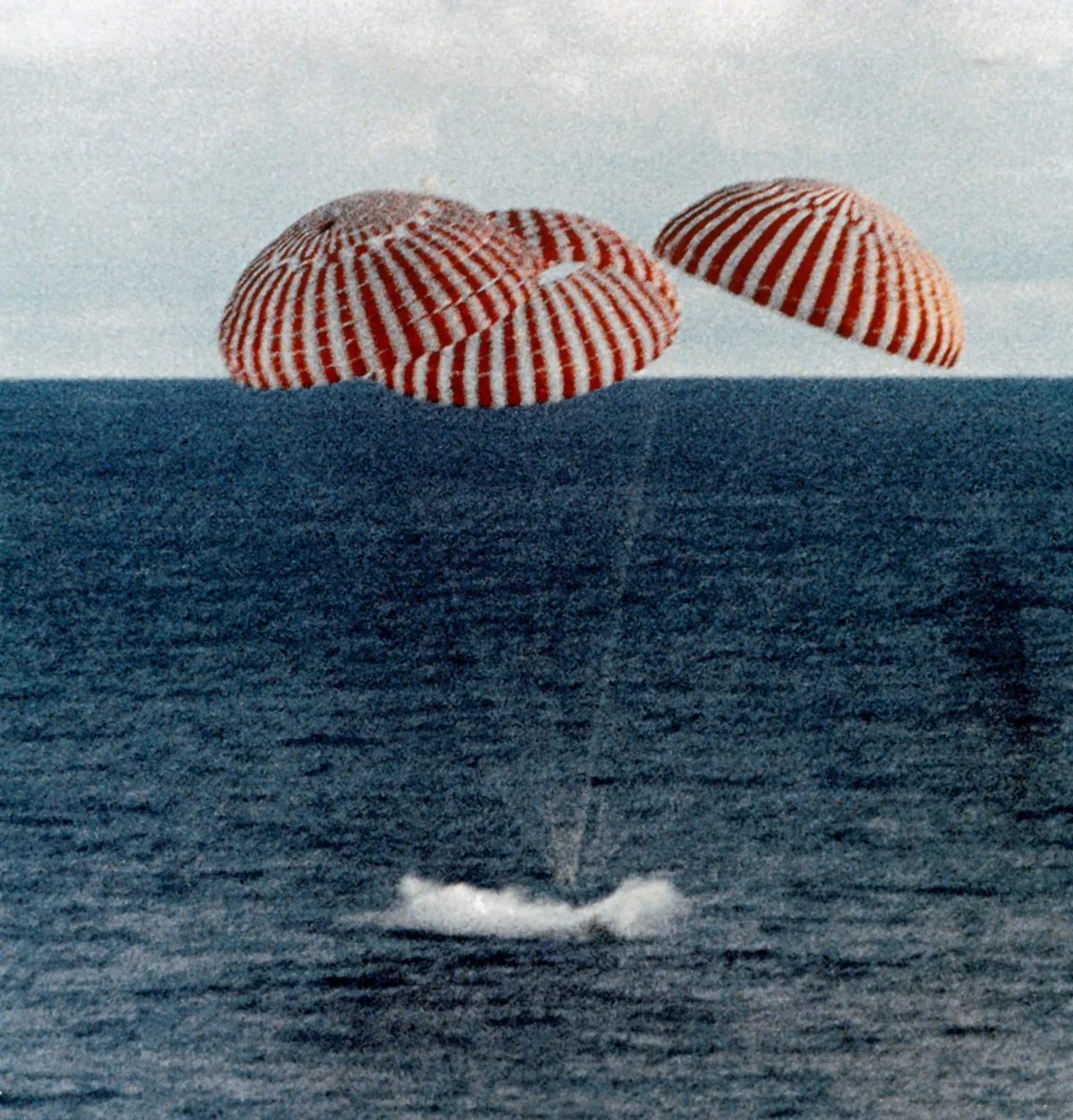

When you compare the rescue to losing the Apollo 1 crew on the launchpad in a fire, what sorrow there was then, to being able to save three guys lives… it still brings a tear to my eye every time I see those three chutes deploy letting us know they were home safely.

We were so proud that we were able to actually take those things that we had done over the years –whether it was through simulations, or engineering meetings or flight control meetings – and save those guys.

We take a huge pride, even to this day 50 years later, about putting a man on the Moon, but I submit to you that the world equals the rescue of Apollo 13 to putting a man on the Moon. It was a wonderful thing.

After the rescue I worked in a group called the New Initiatives Office, working to come up with the next big step in space. It’s difficult. How do you come up with a way of selling the next thing in space that would equal what happened Apollo 11 or 13?

We still have that challenge right now as we talk about going back to the Moon with Artemis. I like this new goal of getting back to the Moon in four or five years because I’ll still be here!

I’ve been at the Johnson Spaceflight Center for 54 years, I’m number seven in longevity. I’m one of the only ones who can tell these stories because I was there when it happened.