NASA's Galileo probe was a mission that studied Jupiter and its moons, arriving in orbit on 7 December 1995 and lasting until 21 September 2003.

When the Galileo spacecraft drifted serenely away from Space Shuttle Atlantis in October 1989, the romance of adventure and the triumph of human ingenuity converged for a long-awaited voyage to Jupiter. Galileo remains one of the most successful missions ever undertaken.

The Galileo mission revealed the Solar System’s largest planet in astonishing detail, closely examined its atmosphere and immense magnetic field and shed new light on its many moons.

The hardy little explorer also scored two asteroid encounters and was in the right place at the right time to catch the cometary impact of the century.

Named for the Italian polymath Galileo Galilei, who discovered Jupiter’s four large moons (known as the Galilean moons) - Ganymede, Callisto, Io and Europa - the mission was green-lighted for development in 1977.

Hopes to launch it in 1986 came to nothing following the Space Shuttle Challenger accident and Galileo’s powerful Centaur booster was cancelled on safety grounds.

A new plan with a less powerful booster and an intricate series of planetary gravity assists (called ‘VEEGA’) was adopted in its stead.

Galileo zipped past Venus once and Earth twice to reach Jupiter in six years.

Approaching Earth, it successfully tested astronomer Carl Sagan’s hypothesis that a planet’s ingredients for life - including absorption lines from chlorophyll in photosynthesising plants - could be detected from space.

This was a key moment in our attempt to answer the question 'will we ever find life beyond Earth?'.

It visited two asteroids, 12-mile-wide Gaspra and croissant-shaped Ida, the latter of which has a tiny moon, Dactyl.

And in 1994, Galileo afforded us a ringside seat as Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 smacked into Jupiter at 134,000 mph with an explosive yield hotter than the surface of the Sun.

But the mission endured its fair share of bumps on the road.

It suffered tape recorder and camera problems, battled radiation levels four times higher than expected and in 1991 its 16-foot-wide high-gain antenna only partially unfurled, due to a lack of lubricant.

Workarounds were developed using its low-gain antennas, electronically linking ground stations and employing sophisticated data-compression techniques to meet its goals.

And those goals encapsulated not one mission but two, for as well as putting an instrument-laden mothership into long-term orbit at Jupiter, Galileo also dropped a tiny probe directly into its hellish atmosphere to take soundings from this alien world.

The greatest surprise was Europa, which Galileo found to have warm ice or even liquid water beneath its crust. That finding satisfied a key criterion for life beyond Earth.

Probe and planet collided at 106,000 mph in December 1995 and for 57 minutes Earth’s robotic emissary endured crushing pressures 230 times greater than terrestrial sea-level.

It recorded 330 mph winds but very little water and a surprising scarcity of lightning.

The probe had entered an uncharacteristically ‘dry’ patch of atmosphere and Galileo later detected water vapour, ammonia clouds and lightning strikes 1,000 times stronger than on Earth.

With the probe gone, Galileo settled in for at least two years (it turned out to be nearly eight) circling a planet so huge that it could comfortably gobble 1,300 Earths.

And despite taking massive radiation hits from Jupiter, it performed far beyond expectations; so much so that its epic voyage was twice extended with a Galileo Europa Mission in 1997-2000 and a Galileo Millennium Mission in 2000-2003.

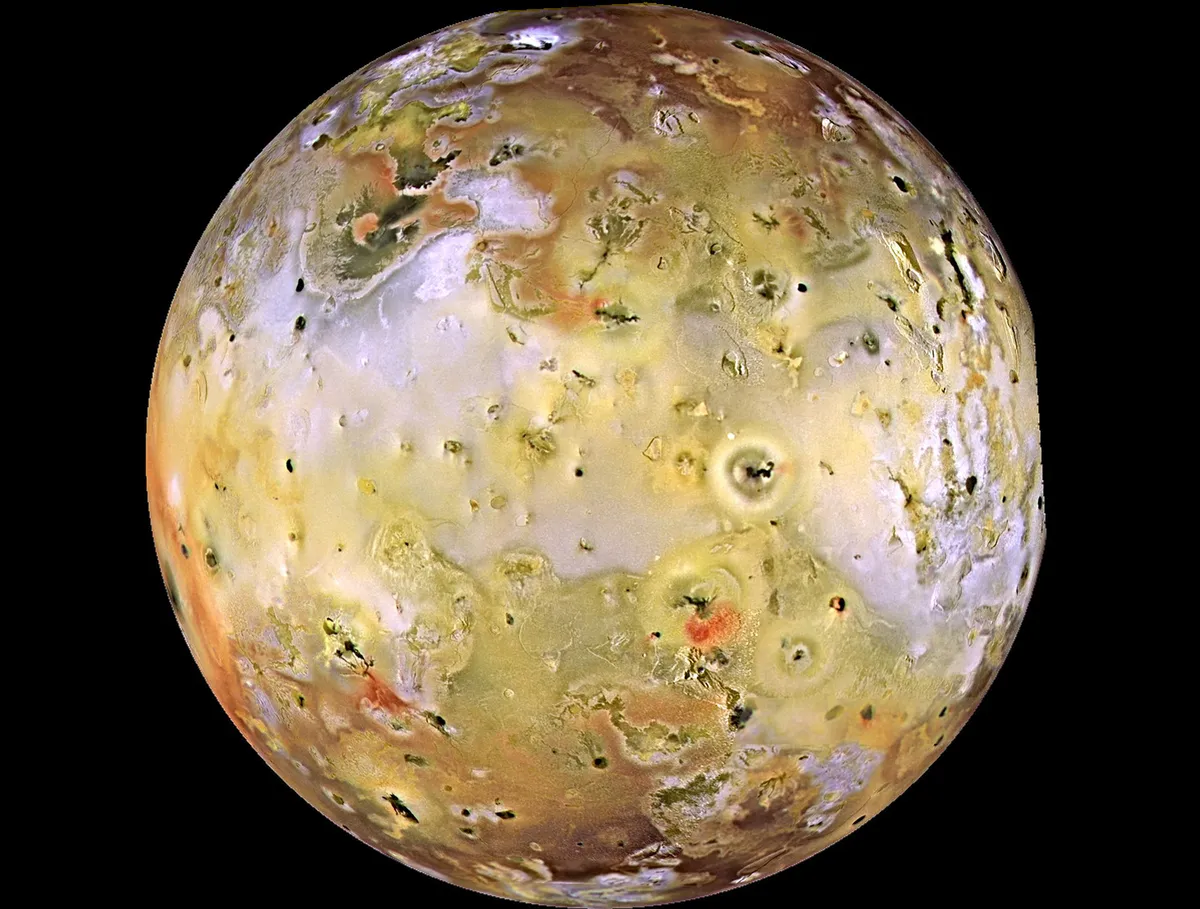

It revealed that Io the most volcanically active place in the Solar System has a giant iron core and 120 hotspots, a consequence of its pizza-like surface being endlessly stretched and squeezed by Jupiter’s gravity.

Galileo pinpointed high-temperature silicate volcanism, with some vents sizzling as high as 1,700 Celsius and one location producing a 300-mile-high plume in what has become the closest real-world analogy to the early Earth.

All four large moons were found to possess atmospheres: a thin carbon dioxide veil around Callisto, an electrically charged ionosphere at Io, and Ganymede became the first planetary satellite known to have a self-generated magnetic field.

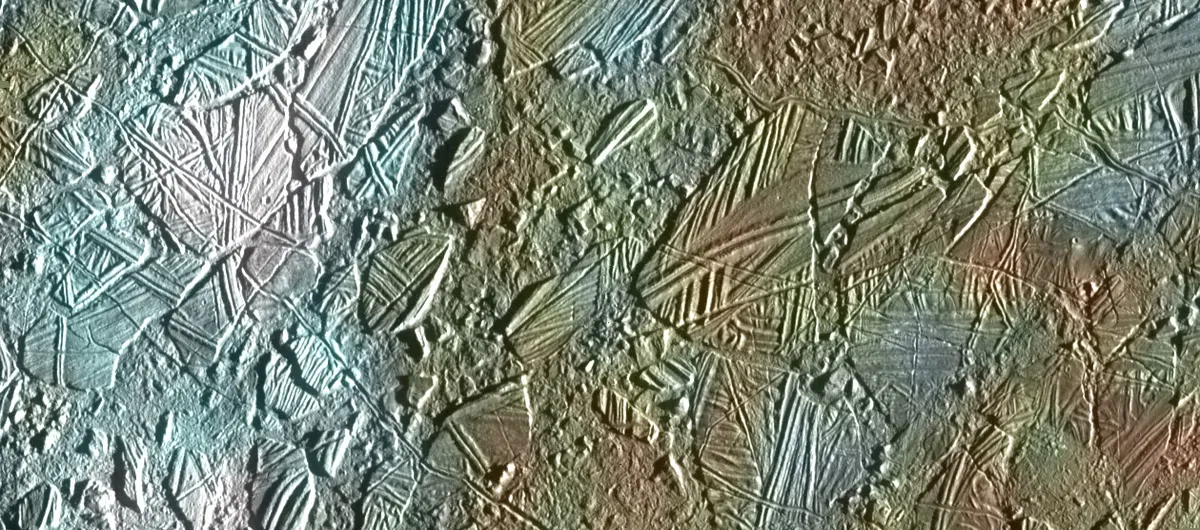

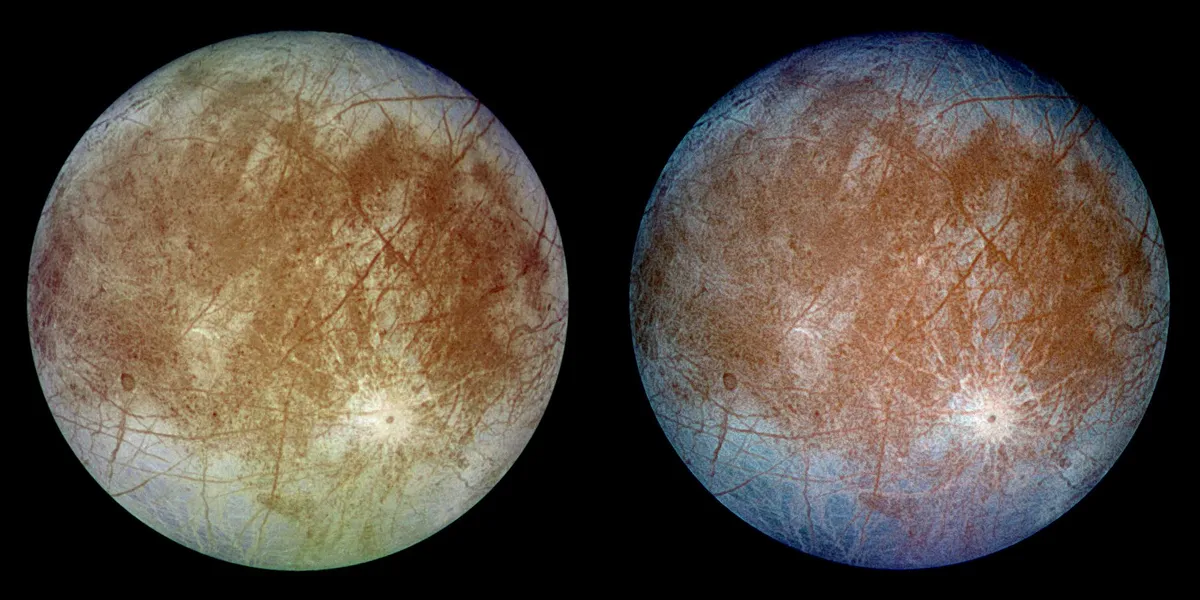

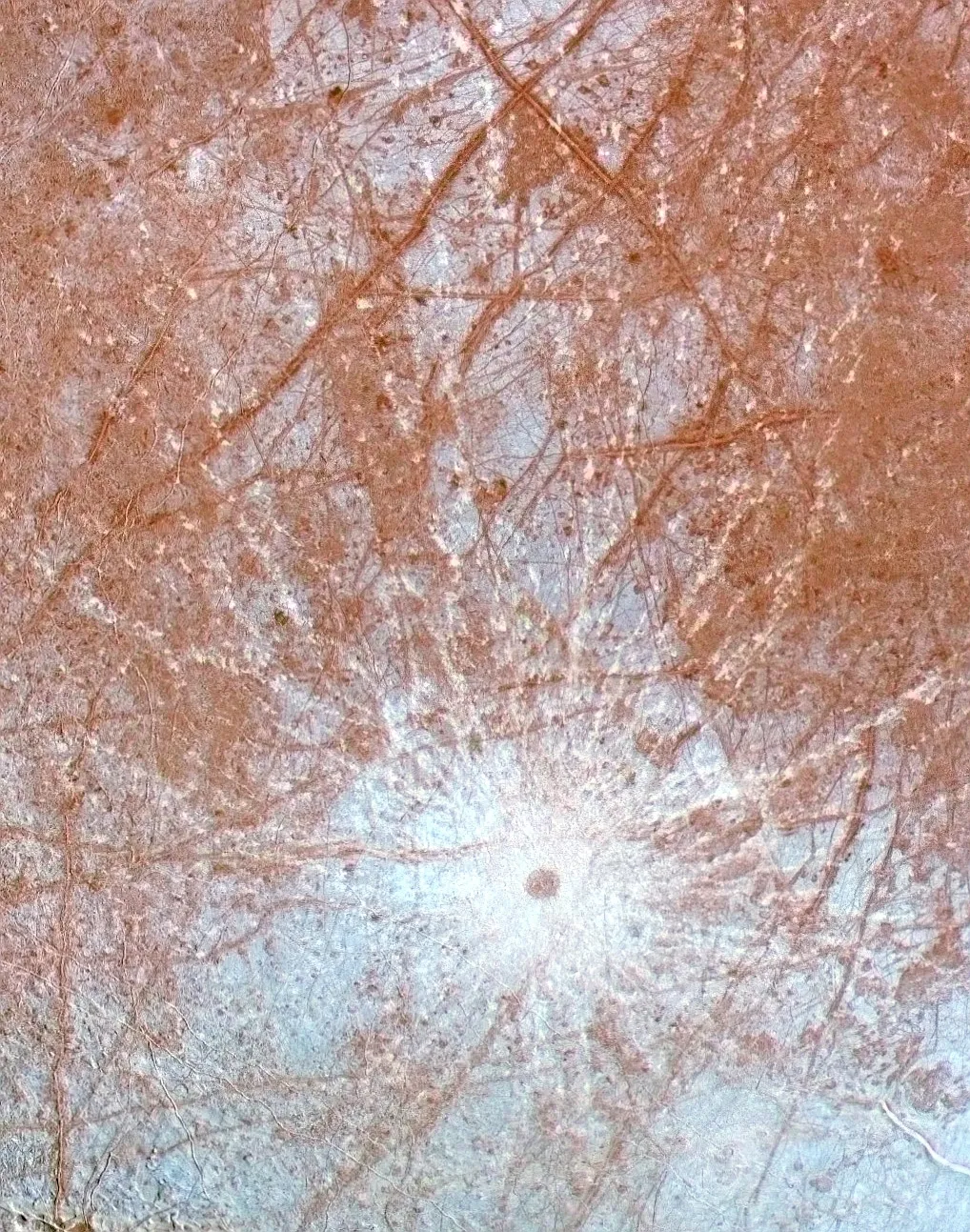

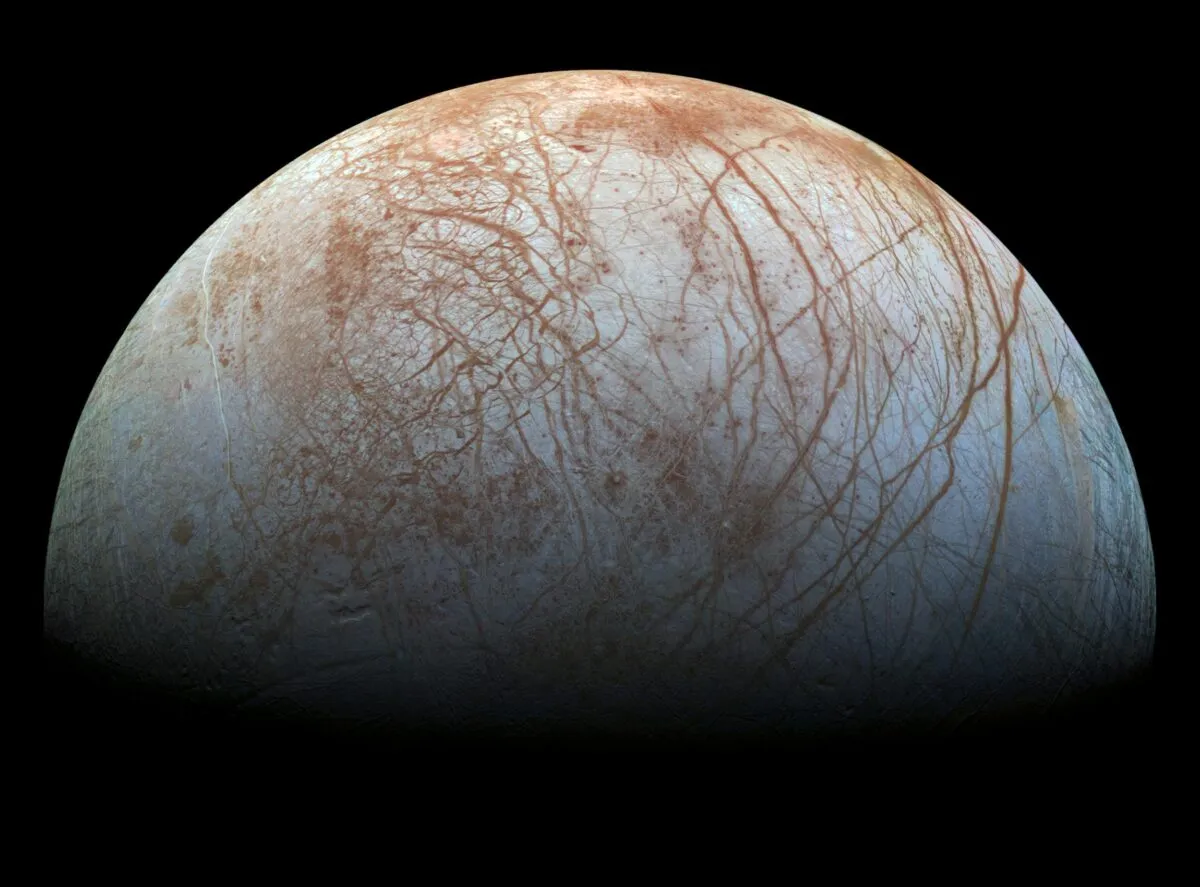

Both it and Callisto offered tantalising hints of salty subsurface oceans, but the greatest surprise was Europa, which Galileo found to have warm ice or even liquid water beneath its young, fractured crust.

That finding satisfied a key criterion for life beyond Earth.

Jupiter’s banded atmosphere of psychedelic reds, creams and browns writhed and contorted under Galileo’s gaze.

Rolling eddies were torn apart by powerful equatorial jet streams, enigmatic white oval storms jostled for position and observations of the centuries-old Great Red Spot revealed the central column of this high-pressure anticyclone to be cooler and higher in altitude than neighbouring clouds.

It found a 700,000-mile-wide dusty band around Jupiter and showed the planet’s tenuous rings arose from material kicked up by micrometeorites blasting the innermost moons Thebe, Adrastea, Metis and battered Amalthea, the last Jovian satellite visited by Galileo.

And with the Amalthea flyby, the mission neared its end.

Low on fuel and with an elevated risk of contaminating pristine Europa, Galileo was intentionally destroyed in Jupiter’s atmosphere in September 2003.

Fourteen years since launch, it circled the giant planet 34 times, travelled 2.8 billion miles, returned 30 gigabytes of data and snapped 14,000 photographs.

Its popularity even spawned a Hot Wheels Galileo toy.

Galileo whetted appetites for future missions and its findings at Europa have led directly to plans for a dedicated orbiter in the mid-2020s.

Its measurements of the Jovian atmosphere and magnetosphere have been continued since 2016 by the Juno probe, for which finding Jupiter’s elusive water is a principal mission objective.

As Galileo project scientist Torrance Johnson once remarked: “We haven’t lost a spacecraft; we’ve gained a stepping-stone into the future.”

A Galileo Gallery

More stunning images captured by the Galileo spacecraft on its long mission at Jupiter