In 1959, William Randolph Lovelace, the physician in charge of determining who was physically suited to spaceflight, had been curious about how the female body would respond to his tests.

He’d secretly called in several women, 13 of whom passed the first stages.

He went public with the results, hoping to garner support for further tests, which would require access to military facilities.

Instead, many at NASA, including several of the male astronauts, pushed back against the idea.

Rather than ban women outright, NASA insisted that candidates needed jet pilot experience which could only be gained in the military – and which did ban women from flying.

The tacit ban would remain in place until 1977, when NASA was selecting its first astronaut class in eight years.

Apollo was long over and the agency was looking to crew its new project, the Space Shuttle.

With a capacity of eight people, the programme would require many new astronauts.

Equal rights for women and for people of colour had become far more prominent in the West since the last astronaut intake, and so the requirements were broadened to accommodate a more diverse range of people.

To push the applicant call to as many people as possible, NASA advertised on TV, radio and in newspapers.

It was reading the latter that brought the initiative to the attention of PhD student Sally Ride.

A highly active person, Ride had found her first love in the world of tennis.

Her prowess at the sport netted her several scholarships to study physics at university and, despite training for hours every day, she excelled academically.

She eventually went to Stanford University for her PhD. It was when she was about to graduate and wondering what direction to take her life that Ride spotted the advert.

"The moment I saw that, I knew that that’s what I wanted to do… I wanted to apply to the astronaut corps and see whether NASA would take me and see whether I could have the opportunity to go on that adventure," Ride said in a 2006 interview at the US Astronaut Hall of Fame.

Making the final cut

In all, 8,079 people applied and just 35 were chosen. Among them were one Asian-American man, three African-American men and six women, one of whom was Ride.

After completing basic training in 1978, Ride worked within NASA on the Shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System, Canadarm, as well as acting as CapCom on two missions, being the link between ground control and the astronauts in orbit.

The first six crewed flights of the Shuttle were flown with smaller crews from earlier astronaut classes, but by the seventh flight, STS-7, it was time for the class of 1978 to take their seats, and one of them would be a woman.

The mission would require Canadarm, with which Ride was well-experienced, but it was Ride’s ability to get along with and work alongside almost anyone that led to her being selected to be the first American woman in space.

NASA had seen the impact being ‘the first’ could have on an astronaut’s life with Neil Armstrong, so officials asked if Ride was willing to accept that fame.

She agreed, but in truth Ride had little comprehension of how intense the attention would be.

While Valentina Tereshkova, the cosmonaut who in 1963 became the first woman in space, had been somewhat protected by the Soviet Union’s policy of not publicising missions until they were under way, Ride was under the microscope from the moment her assignment was announced.

"Really the only bad moments in our training involved the press," Ride said in an interview with feminist Gloria Steinem.

"Whereas NASA appeared to be very enlightened about flying women astronauts, the press didn’t appear to be. Without a doubt, I think the worst question that I’ve gotten was whether I cried when we got malfunctions in the simulator."

She endured the questions and on 18 June 1983 the first American woman headed to space on board the Challenger Space Shuttle.

"The view of Earth is absolutely spectacular, and the feeling of looking back and seeing your planet as a planet is just an amazing feeling," said Ride in the 2006 interview.

"It’s a totally different perspective, and it makes you appreciate, actually, how fragile our existence is."

Ride's flair for spaceflight

Sally Ride thrived in orbit. Unlike many new astronauts, she didn’t experience any form of space nausea

– a little ironic given the crew was meant to test new space-sickness medication, which she couldn’t do.

Instead, she dedicated herself to the main task of releasing three new satellites.

Two of these were communications satellites, while the third was the Shuttle Pallet Satellite SPAS-01, which would test the formation of alloys in microgravity.

During the deployment procedure, she manoeuvred the robotic arm into the shape of a ‘7’ to celebrate the flight.

After a six-day mission, the Shuttle headed home.

Bad weather forced it to divert its landing to Edwards Air Force Base in California, but it was one of only a few hiccups in an otherwise flawless mission.

Ride’s flight had proved women could not just handle spaceflight but excel at it.

In the years since, there has been a global push to increase female engagement with space and science.

Astronaut classes from NASA, the European Space Agency and other nations have included an ever-increasing number of female candidates – many of whom cite both Ride and Tereshkova as inspirations.

Just over 70 women have flown in space, out of a total of around 600 people, but the number is growing as more and more women are being assigned to missions.

With NASA’s Artemis programme in full swing, it won’t be long until one of them takes 'one giant leap for womankind'.

After NASA

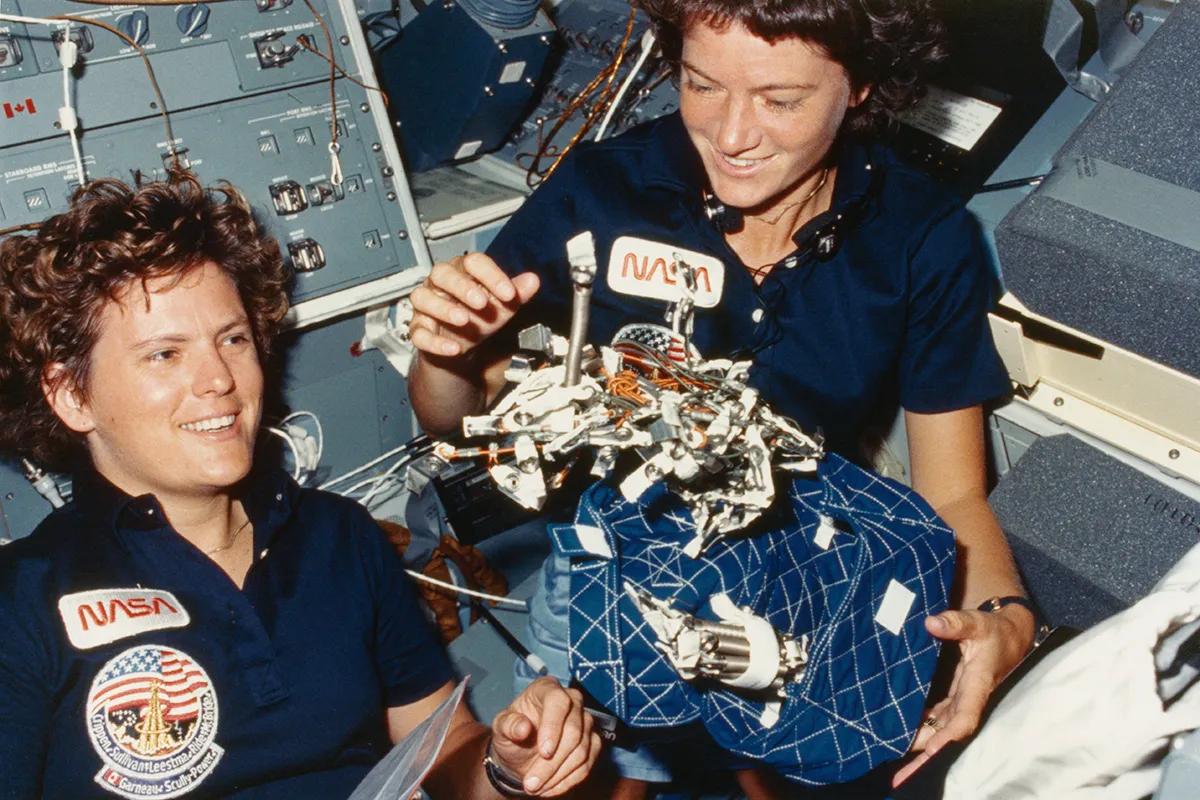

After her flight on STS-7, Ride stayed with NASA and flew a second Shuttle mission, STS-41-G, in October 1984.

She was joined on board by Kathy Sullivan, making it the first space mission with two women.

It also made Ride the first US woman to fly in space twice and Sullivan the first US woman to perform a spacewalk, though cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya had claimed both of these world firsts a few months earlier.

Ride was scheduled for a third flight, but this was cancelled following the Challenger disaster.

Instead, she was appointed to the commission investigating the accident, leading to a more managerial role at NASA, planning the agency’s future.

She left NASA in 1987, taking various university professorial posts, although she continued to work with NASA on outreach programmes.

She set up Sally Ride Science to encourage children, particularly girls, into taking up science

Both presidents Clinton and Obama offered her the role of NASA administrator, but she turned them down.

Ride married fellow astronaut candidate Steven Hawley, but later divorced.

After her death on 23 July 2012, her family revealed (with Ride’s consent) that she had been in relationships with both men and women throughout her life and had been with female partner Tam O’Shaughnessy for 27 years, making her the first known gay astronaut.

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.