One of the most ancient and enduring uses of astronomy lay in the construction of religious calendars to ensure that particular acts of worship took place at the correct time of the year.

The eighth-century-BC Greek writer Hesiod, in his Works and Days, brings home to us the importance of astronomy to both religion and agriculture in the pre-scientific Greek world.

Indeed, modern scholars, with the aid of computer programs that enable them to back-calculate the heavens to a given date in the past, have been able to use astronomy to explain details in many ancient texts.

More history of astronomy:

- Was Stonehenge used for astronomy?

- Can astronomy explain why the Egyptians built the pyramids?

- A guide to ancient Chinese astronomy

In their 2005 paper ‘Knowing When To Consult The Oracle At Delphi’ (Antiquity, 79 (2005), p564-572), Alun Salt and Efrosyni Boutikas of Leicester University cast new light on the consultation of the famous Oracle at Delphi in Greece.

At that time, around 750 BC, different parts of the Greek world had different calendars.

One wonders at how people from across that world were able to coordinate their travels to arrive at the mountainous shrine of Delphi for the seventh day of the month Bysios.

This was the god Apollo’s birthday, upon which the Oracle’s statements were issued to the faithful.

To confuse matters further, the Greeks used a lunar calendar within a solar year that began and ended with the summer solstice.

Thus Bysios could move, depending on when the new Moon fell, between – in our calendar – late January and mid March.

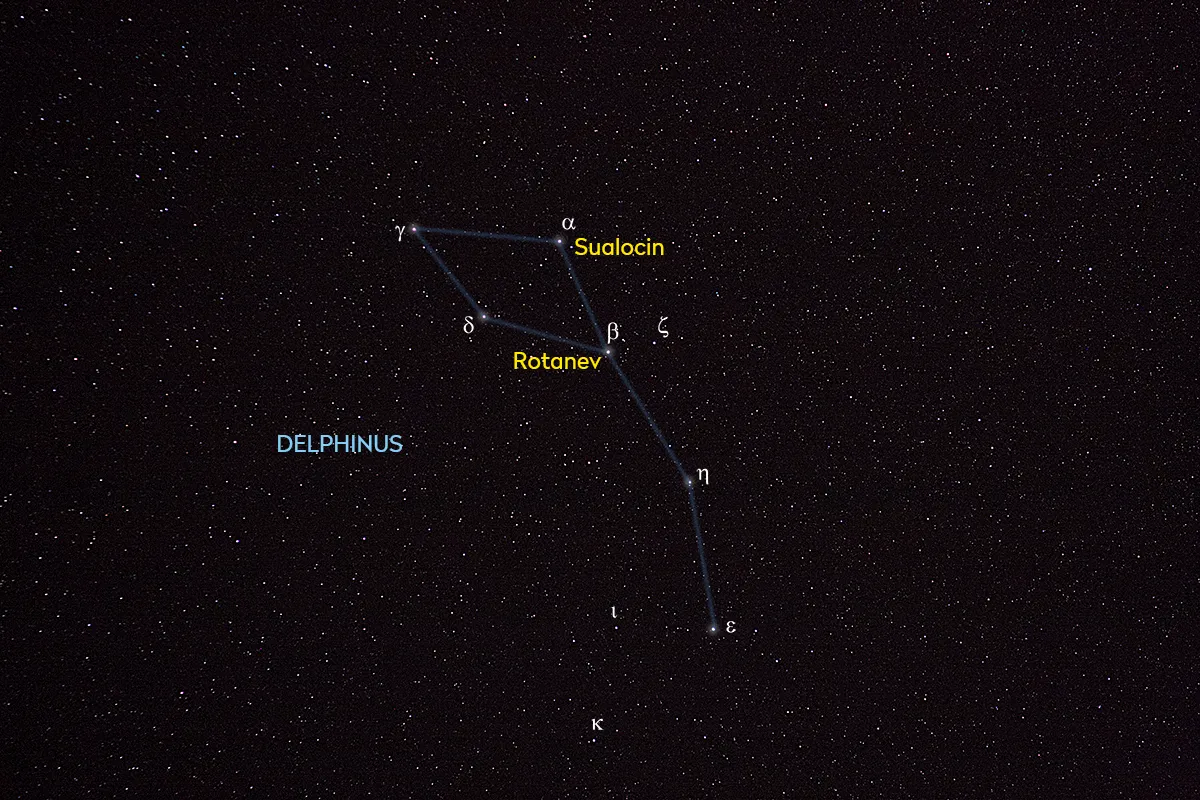

It has been calculated, however, that around 750 BC the stars in the constellation of Delphinus rose just before the Sun – displaying a heliacal rising – at the very end of December.

This would have produced an astronomical event that could have been seen all across the Greek world and elsewhere, and would have acted as an international time signal.

In the lunar calendar of the Greeks, this would have signalled that the next month would be Bysios, and that the time of the year had arrived to set out for Delphi, in the foothills of Mount Parnassus, above the northeastern end of the Gulf of Corinth.

Travellers could then be present for the god’s birthday and could seek his advice at this, the most sacred oracle in Greece.

It would have given worshippers a month’s travelling time.

Of course the heliacal rising of Delphinus does not happen after the winter solstice today. A slow change in sky alignment has taken place, caused by the precession of the equinoxes over 2,750 years.

This article originally appeared in the March 2006 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.