Chinese astronomers have been studying the night sky for longer than any other culture. The oldest star maps and the earliest records of sunspots have been unearthed by archaeologists in China, where a unique way of looking at the night sky developed about 1,200 BC.

Chinese astronomers Gan De and Shi Shen are credited as the first to create star catalogues in the 4th century BC, and the Buddhist monk Yi Xing conducted an astronomical survey in the 8th century AD to help with the prediction of solar eclipses.

Discover more guides like this via our History of Astronomy webpage.

Chinese or Lunar New Year starts on the day after the first new Moon that falls between 21 January and 20 February (in the Gregorian calendar) and ends with the next full Moon.

You may also know about the ancient Chinese belief that a solar eclipse occurs when a dragon eats the Sun.

What you may not know is that Chinese astronomers were the first to make a reliable recording of a total solar eclipse (780 BC) and the passing of Halley’s Comet (239 BC).

China's constellations

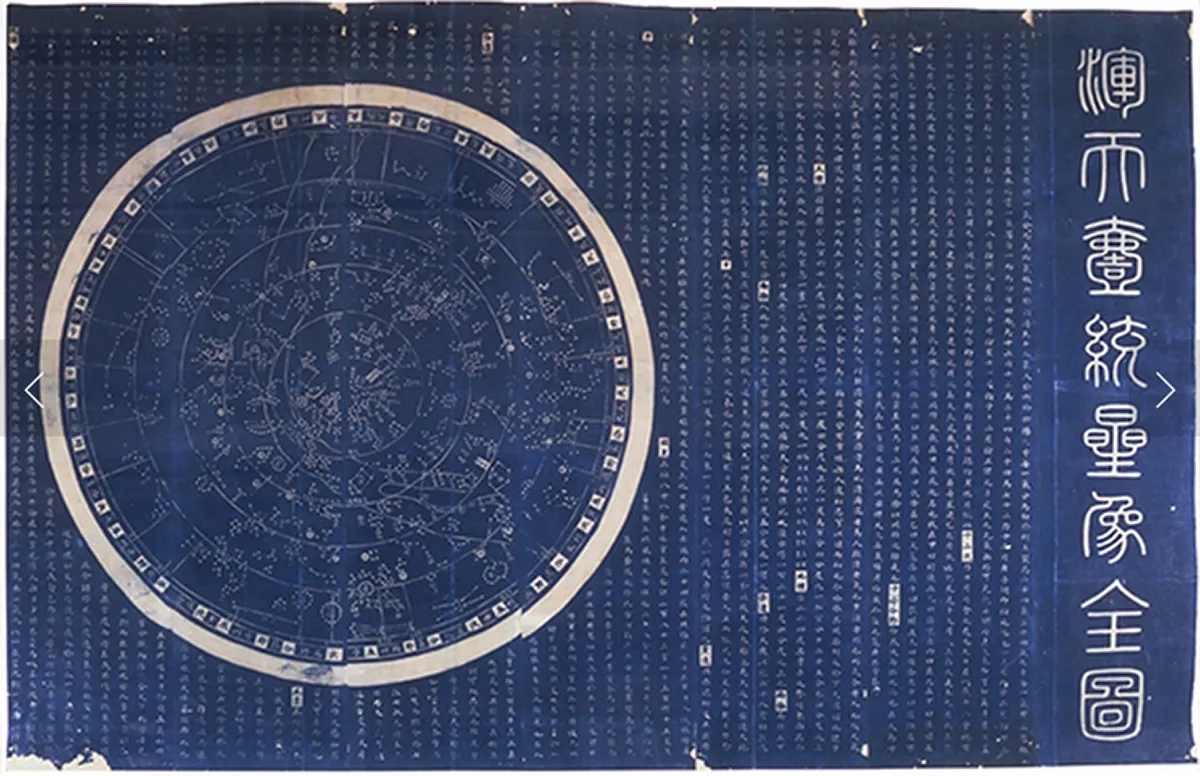

China’s star lore divides the sky into four groups of 283 asterisms (‘xing guan’). Three of the groups are ‘enclosures’ of stars close to Polaris (Alpha (α) Ursae Minoris). For advice on locating Polaris, read our guide on how to find the North Star.

Surrounding Polaris are the ‘Purple Forbidden enclosure’ (which includes Ursa Minor), the ‘Supreme Palace enclosure’ (including Virgo, Coma Berenices and Leo) and the ‘Heavenly Market enclosure’ (with Serpens, Ophiuchus, Aquila and Corona Borealis).

The fourth group comprises the ‘Twenty-Eight Mansions’ (groups of stars) that are themselves divided into four groups of seven symbols.

Within these symbols are many easily identifiable asterisms and star clusters.

For example, within the ‘White Tiger of the West’ symbol (which is equivalent to Taurus, the Bull) are the ‘Shen’ (‘Three Stars’) and the ‘Mao’ (‘Hairy Head’) mansions – known in the west as Orion’s Belt and the Pleiades open cluster, respectively.

It was in this ‘White Tiger of the West’ region of the night sky that, in AD 1054, Chinese astronomers saw a new and very bright star.

It was a supernova, also noted by Japanese, Korean and Arab astronomers, which today we know as its remnant – the Crab Nebula, M1.

China's space programme

With a pivotal place in astronomy’s past, China is also poised to influence its future. Recent years have seen a growth in astronomical and astrophysical science in China. It’s now the world’s second most prolific nation in astronomy and space research, after the US.

That thirst for astronomical knowledge is backed-up by hardware and space missions. In 2016 the £127 million Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST) in Guizhou, southwest China, also nicknamed ‘Tianyan’ (‘Heaven’s Eye’), was opened to detect Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) and pulsars.

The world’s largest single-dish radio observatory, FAST’s importance has been accentuated by the demise of the Arecibo telescope.

It looks set to become a world-class facility. Astronomers using FAST have newly identified around 300 pulsars so far and want to use it to find the first pulsar outside the Milky Way.

FAST will also be used for sky surveys, to search for exoplanets with magnetic fields, and to map gas clouds between stars. It will perform SETI surveys, listening for signals from any alien civilizations out there.

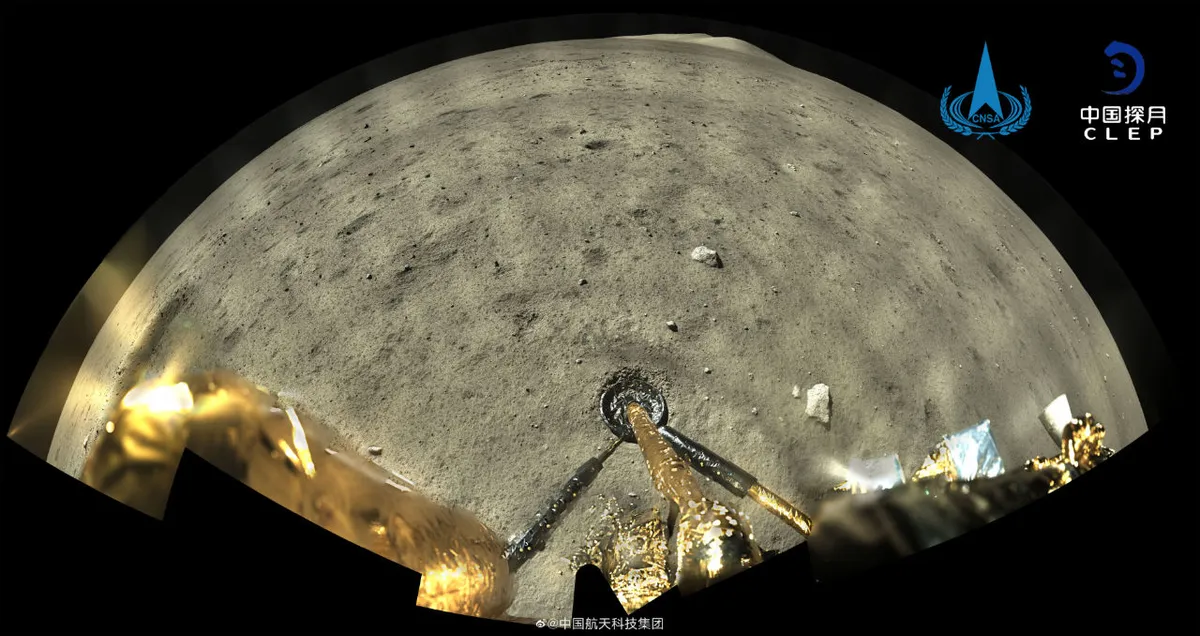

The China National Space Administration’s Chang’e 5 mission – named after the Chinese goddess of the Moon – returned 1.7kg of samples from the Moon in December 2020.

The following month, China gave FAST an ‘open sky’ policy, offering up the dish to observations by astronomers worldwide.

Then in February 2021 the CNSA’s Tianwen-1 spacecraft arrived at Mars. In May 2021, the world finally got to see the Zhurong rover's first images of Mars.

Following its achievement in becoming the second country to deploy a rover on the Red Planet, the CNSA is also on the cusp of launching a modular crewed space station, the ‘Tiangong’ (‘Heaven’s Palace’).

Proof, if more were needed, that China continues to have its gaze fixed firmly on the stars.

5 of China's biggest astronomy discoveries

1

First recorded sighting of Halley's Comet

On 30 March 239 BC a sighting of Halley’s Comet was recorded in the Shih Chi and Wen Hsien Thung Khao chronicles; in the 2,260 years since, every return has been recorded in China.

2

First reliable record of a solar eclipse

The 4 June 2021 will mark 2,801 years since the first reliable record of a total solar eclipse was made by Chinese observers in 780 BC. (There are etched bones with illustrations that go back further.)

3

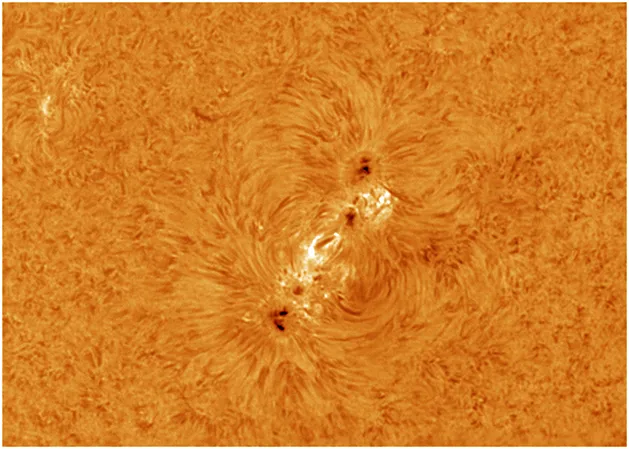

Earliest known observation of sunspots

Official imperial records include a mention of 112 sightings of sunspots between 28 BC and AD 1638, but the earliest recorded observations go back to 364 BC by Chinese astronomer Gan De.

4

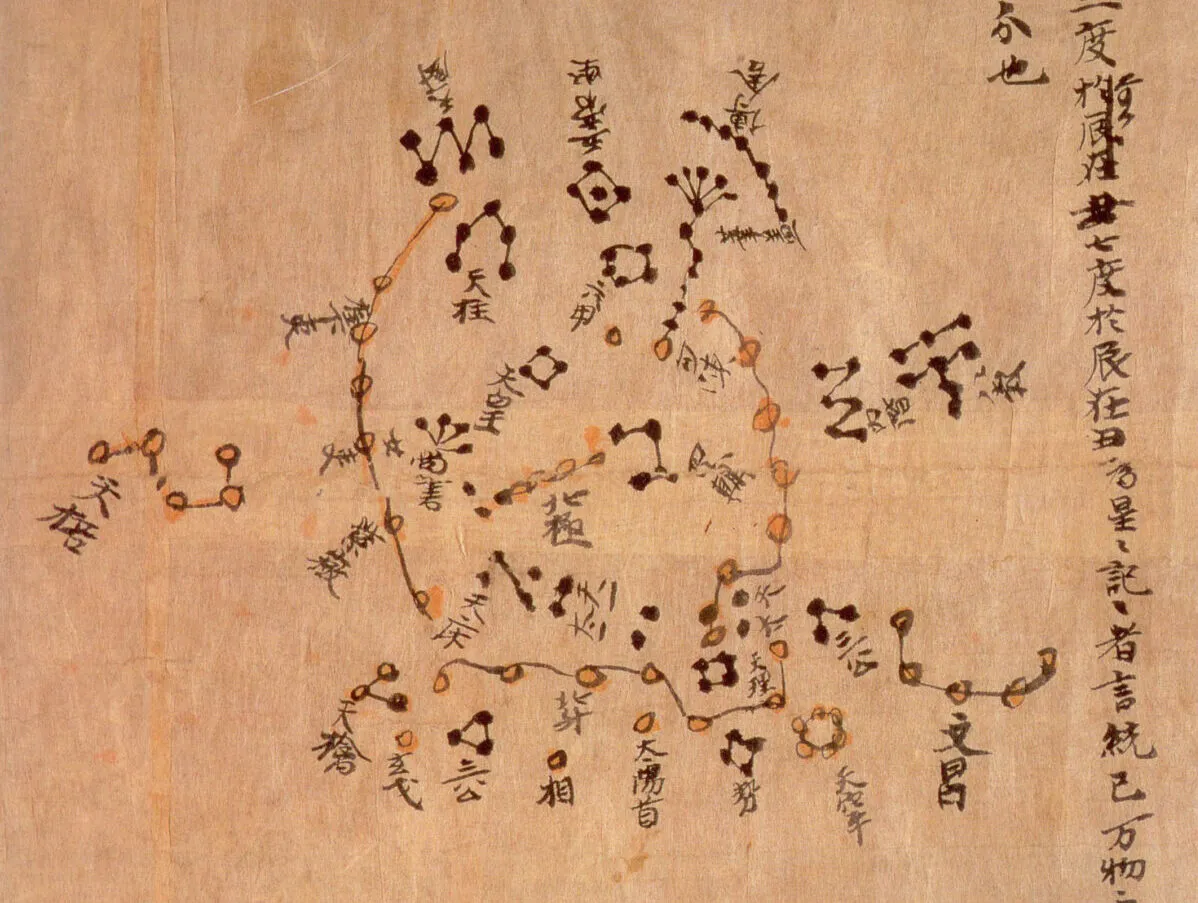

The oldest preserved star atlas

Discovered in caves in 1900, the Dunhuang manuscript of AD 700 is the world’s oldest complete preserved star atlas. Dating to the Tang Dynasty, it maps 1,345 stars in 257 constellations.

5

First record of a supernova sighting

On 4 July 1054, Chinese astronomers recorded a ‘guest star’ in the White Tiger of the West (Taurus), which outshone Venus. The supernova remnant is today’s Crab Nebula.

This guide originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.