Water is escaping from Mars at a far higher rate that previously suspected, perhaps explaining how the wet, lake-hosting Mars of the ancient past became the arid, red desert of today.

The discovery has been published in the journal Science, based on data from the Mars-circling Trace Gas Orbiter, part of the joint European–Russian ExoMars mission.

The data shows surprisingly high levels of water vapour in the planet’s upper atmosphere, suggesting a process is rapidly dispersing water into space.

Mars has always exhibited great seasonal variability in the degree of water loss into its atmosphere, with more being lost during its warm, stormy seasons.

The international research team has now found that water vapour is accumulating in large quantities and unexpected proportions at altitudes of over 80km above the Red Planet.

The data, gathered during the 2018–2019 Martian southern spring and summer stormy seasons, reveals ‘supersaturated’ regions containing 10 to 100 times more water vapour than its temperature should theoretically allow.

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity found in October 2019 that Mars probably once housed a large, stable lake and possibly rivers of water.

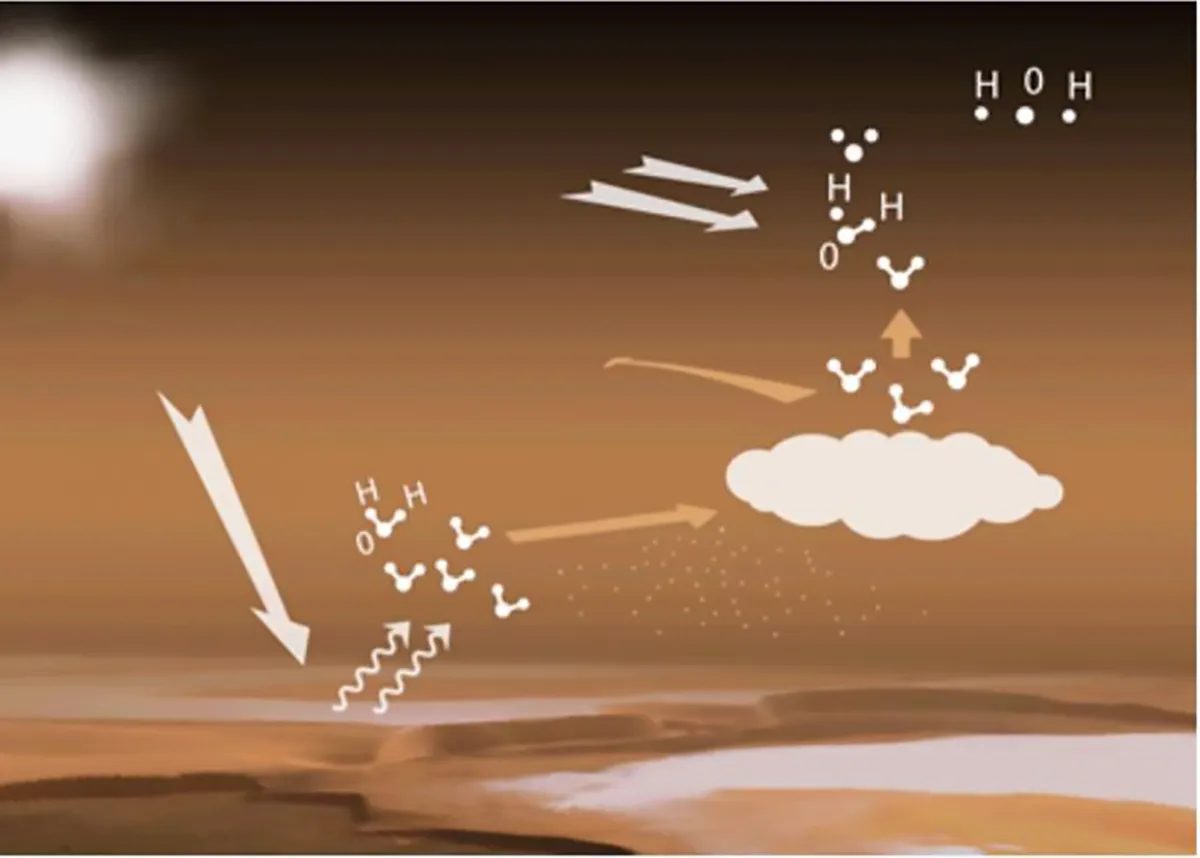

Now water is found only at the planet’s frozen poles, which – in a similar cycle to that found on Earth – are heated by the Sun, releasing water vapour into the atmosphere.

On Mars, however, condensation into clouds is hindered by weak gravity and a thin atmosphere. Atmospheric water molecules are broken apart by sunlight, releasing the two hydrogen atoms from the oxygen atom they are bound to.

The increased presence of water vapour at very high altitudes now suggests that that loss of hydrogen and oxygen atoms into space is happening much faster than previously theorised or observed.

On the face of it, the research is a blow to hopes of finding conditions that harbour life on Mars – hopes that lie behind two new rover missions: the Rosalind Franklin rover and NASA’s Perseverance rover, both due to launch this summer.