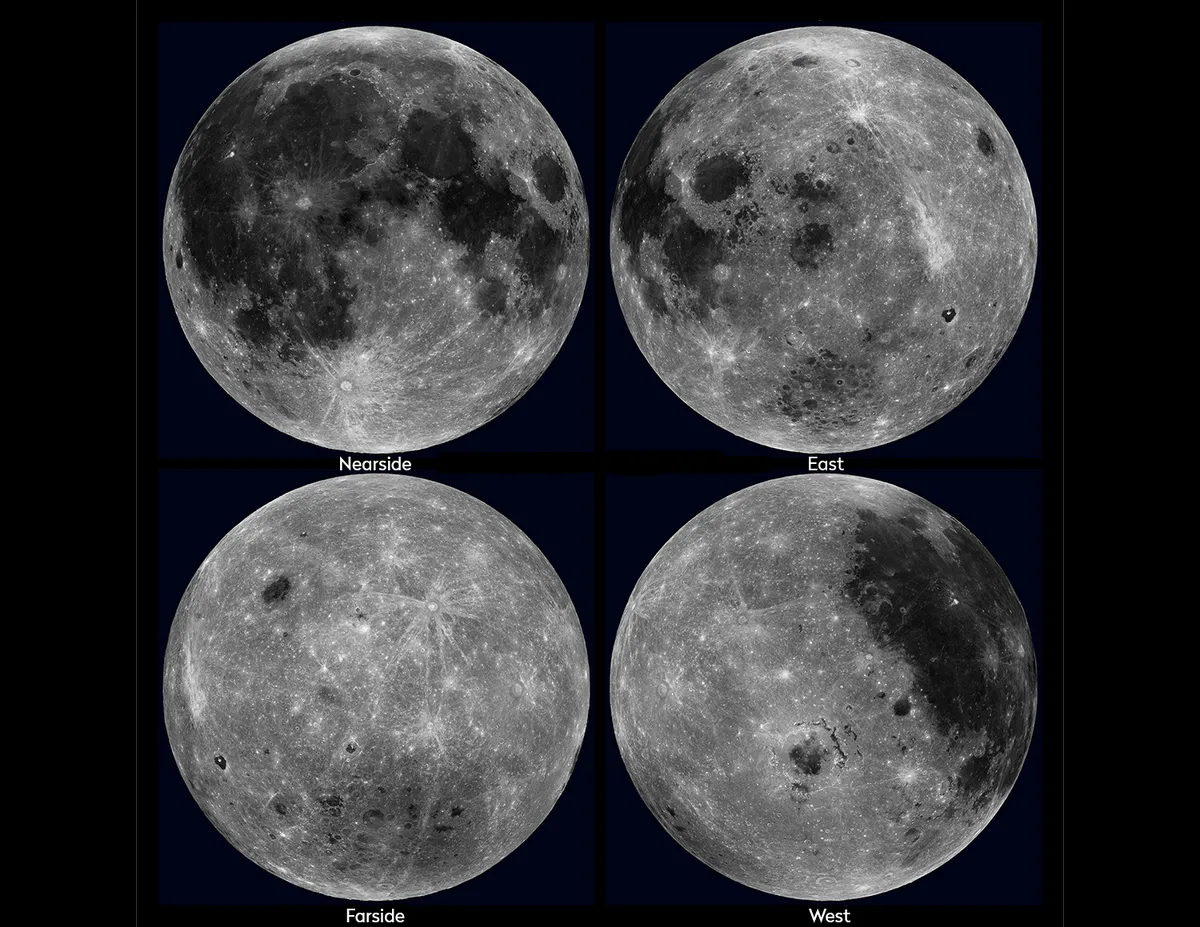

From Earth, we never see the far side of the Moon. Our planet's natural satellite is tidally locked in its orbit, meaning the same side of the Moon always faces us. But what does the other side of the Moon look like, and is there much of a difference between the near side and the far side?

The Moon’s violent genesis as a product of a collision between the proto-Earth and a Mars-sized body some 4.5 billion years ago is now a widely accepted hypothesis.

Once the debris had coalesced into two (possibly three) bodies, Earth’s gravitational pull caused the nascent Moon to become tidally locked to our planet, keeping the same face turned toward our own.

For most of human history the Moon therefore held a closely guarded secret: no one knew what the far side was like.

For more lunar science and observing, read our guide to seeing the Moon during the day, a look at what the Moon is made of and the science behind a supermoon.

While 35% of the Moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere is covered with mare lava, very little molten material made it to the surface on the far side after its formation, so lunar maria account for just 1%.

It’s thought this is because the far side’s crust is thicker (maybe up to twice as thick as that of the near side) possibly due to the slow accretion of a companion satellite after an impact.

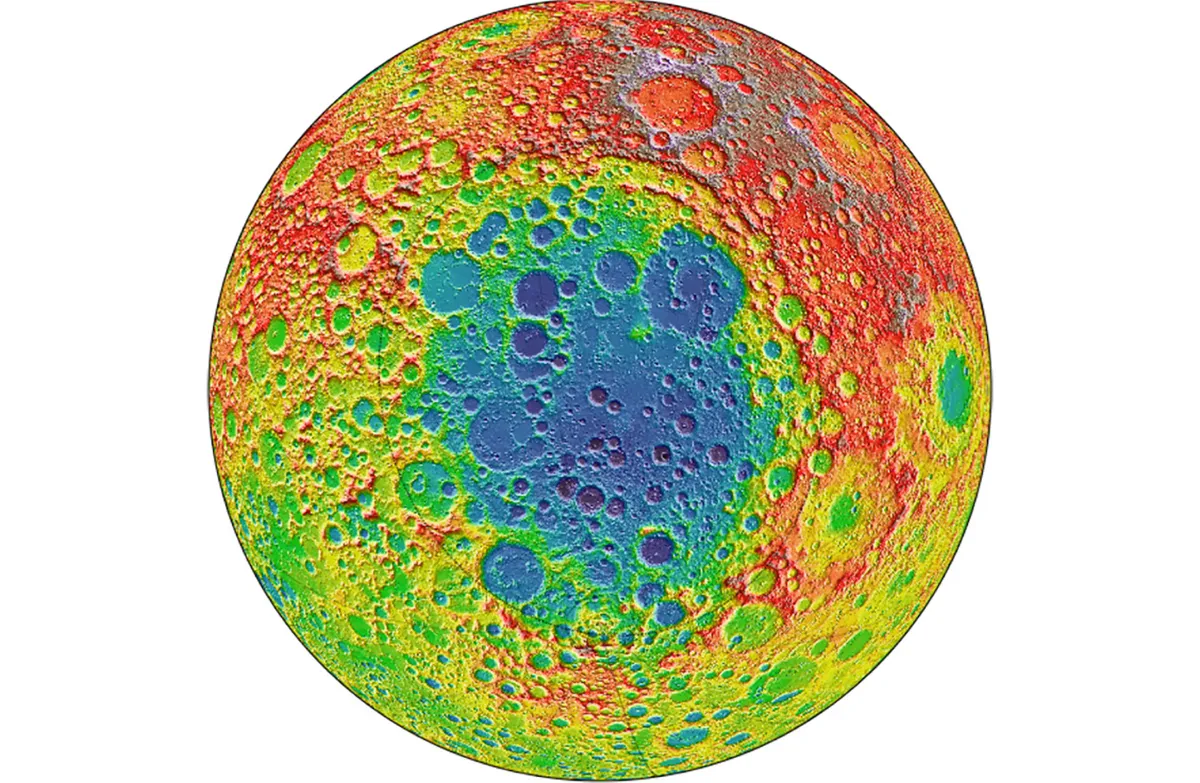

This theory seems to be supported by the discovery of the far side’s 3.9 billion-year-old South Pole-Aitken Basin, over 2,400km wide and around 13km deep. Impact craters of all sizes dominate the far hemisphere.

Contrary to the usual International Astronomical Union naming convention, many of the features on the far side of the Moon retain the Russian names given to them by Soviet scientists.

Many have been named after famous astronomers, such as these 5 women astronomers with Moon craters named after them.

The dark side of the Moon?

The phrase ‘dark side of the Moon’ may evoke fond memories of Pink Floyd’s seminal prog-rock album to the baby boomer generation, but in an astronomical context it’s often used to refer (erroneously) to the Moon’s far side. Like the term supermoon, the phrase can cause a little grievance among some astronomers!

The phrase is something of a misnomer, since the lunar far side goes through the same cycle of illumination as the phases of the Moon seen on the Earth-facing hemisphere.

Technically, the far side is the ‘dark side’ at the instant of Full Moon. The only places on the Moon’s surface permanently bathed in shadow are a few deep craters at the north and south poles.

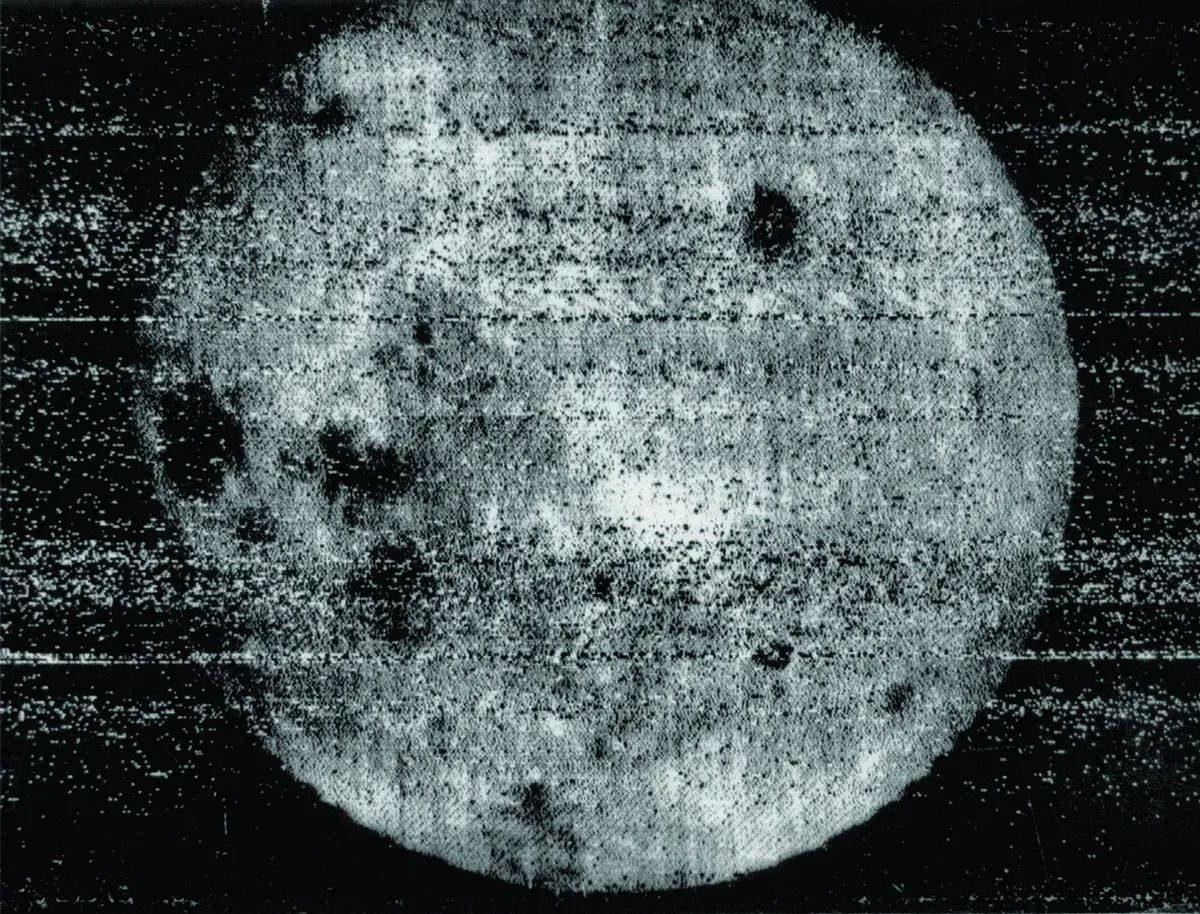

By 1959, Russian space technology had advanced to the level of reaching the Moon. Probes Luna 1 and Luna 2 hit their target (Luna 2 actually crashed into the surface), but Luna 3 was designed to image the Moon’s hitherto unseen side.

In a memorable episode of The Sky at Night broadcast on 26 October 1959, Patrick Moore announced the success of the Soviet mission, revealing the first shadowy photographs of the Moon’s far side live on air.

Luna 3’s imagery was crude by today’s standards, but it revealed that the ‘dark side’ was strikingly different in a number of ways.

Seeing the far side of the Moon

The Moon’s far side was finally seen with human eyes by the crew of Apollo 8 during their historic circumlunar flight of December 1968.

All six subsequent manned lunar landings took place on the Earth-facing side, though geologist turned astronaut Harrison Schmitt of Apollo 17 lobbied hard for a mission to the lava-filled far side crater Tsiolkovsky.

To date, our best views of the Moon come from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) probe.

Multi-spectral imagery of the lunar surface from a height of about 50km means that the Moon is finally yielding its secrets in unprecedented detail, paving the way for a permanent human presence.

If you want to have a go at imaging the lunar surface yourself, read our guide on how to photograph the Moon.

A telescope on the Moon

Radio astronomers have a hard time in the 21st century. The global proliferation of mobile phones, microwaves, TVs and radar generates an electromagnetic ‘smog’ that frequently interferes with (and sometimes obliterates) the faint signals from billions of lightyears away that they wish to study.

Sadly, this is a battle that radio astronomers are frequently losing, which is why they are turning their attention to the Moon.

A radio telescope situated on the lunar near side would be a distinct improvement, but given the ability to construct larger (and hence more sensitive) radio telescopes in the Moon’s lower surface gravity, human electrical interference would be all too evident even from a quarter of a million miles away.

However, on the far side of the Moon, any radio antenna would be shielded from electromagnetic interference by nearly 3,500km of rock

The two-week-long frigid lunar night would also make it easy to keep sensitive detectors super cold.

Ade Ashford is an astronomer and a science journalist. This article originally appeared in the October 2013 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.