Things have been hotting up on the Sun over the last few years. In December 2019, its surface was a very quiet place, a time known as the solar minimum.

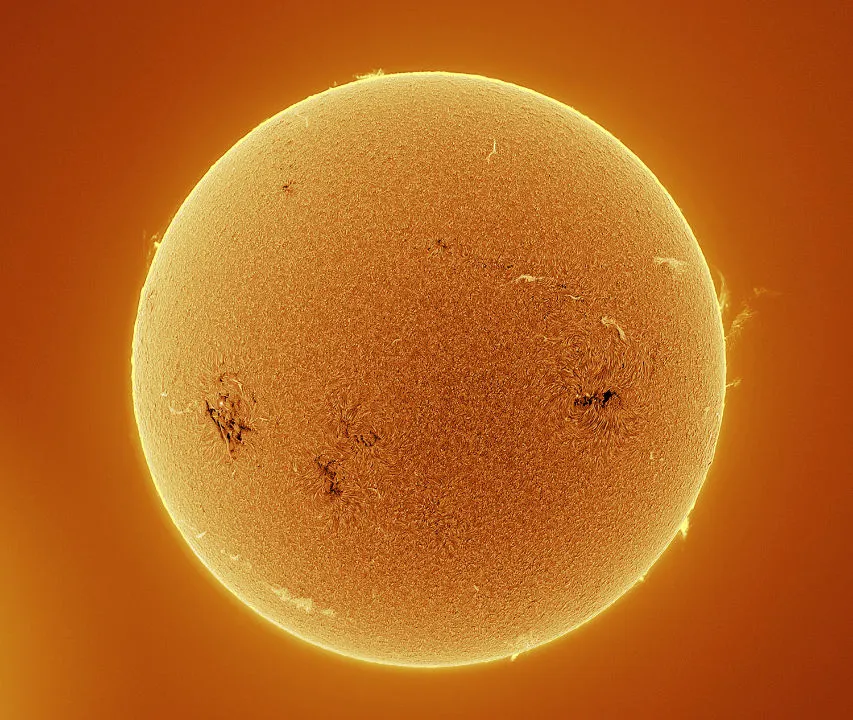

In the years since, it has been gradually waking up, with sunspots and flares being sighted across its surface.

This activity is expected to reach its peak in the coming year or so, after which it will fall back into slumber once more, heading towards a new minimum.

This pattern of rising and falling activity is known as the solar cycle.

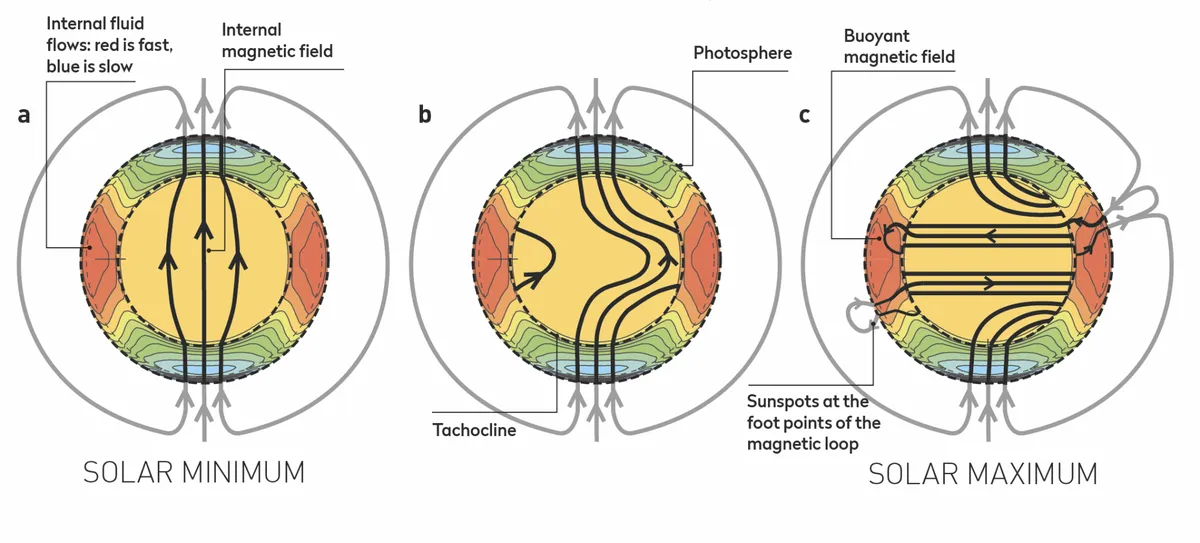

“The solar cycle is driven by the magnetic field of the Sun,” says Stephanie Yardley, a solar scientist from the University of Reading.

“Approximately every 11 years the Sun’s polar magnetic field reverses polarity – it swaps direction.”

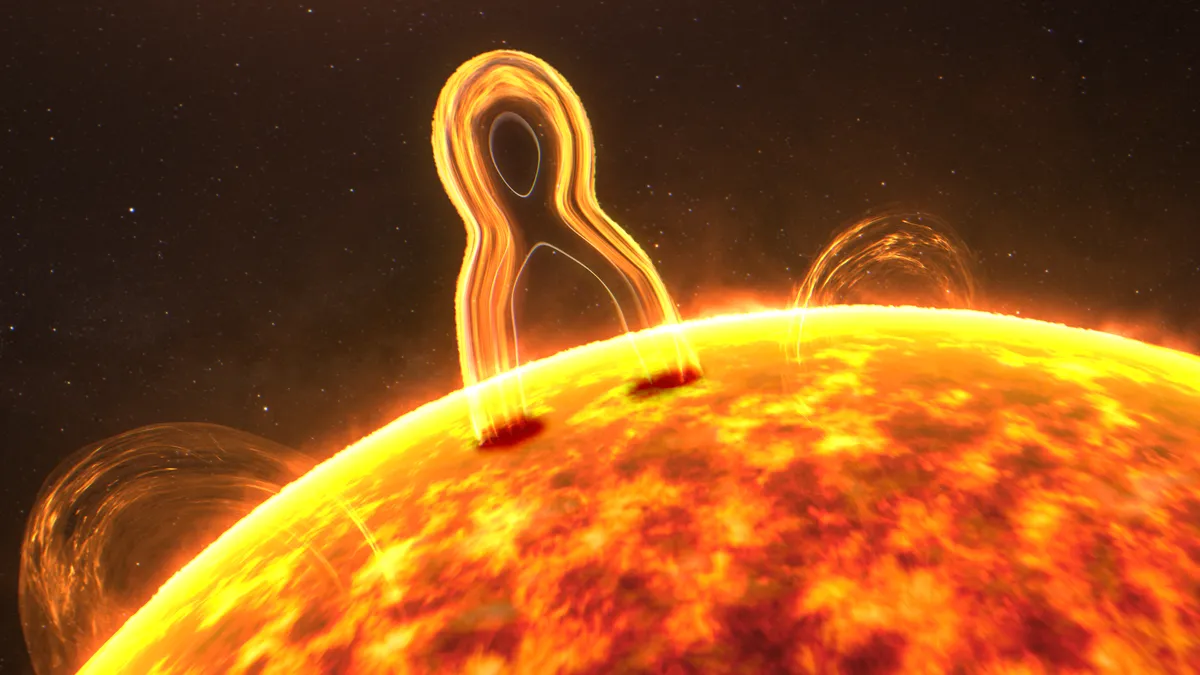

This swapping is a chaotic process, with magnetic field lines becoming tangled and churning up the plasma the Sun is made of, which we see as an increase in solar activity around the solar maximum.

When the poles are holding steadily in place, there is little solar activity and we have a solar minimum.

As the Sun’s magnetic field is difficult to measure, astronomers instead track the solar cycle using something much easier to see: sunspots.

They occur when a magnetic field line breaks through the visible surface of the Sun, preventing the hot plasma in a specific spot from mixing properly.

This creates a cool patch, which we see as a dark blemish on the visible surface of the Sun.

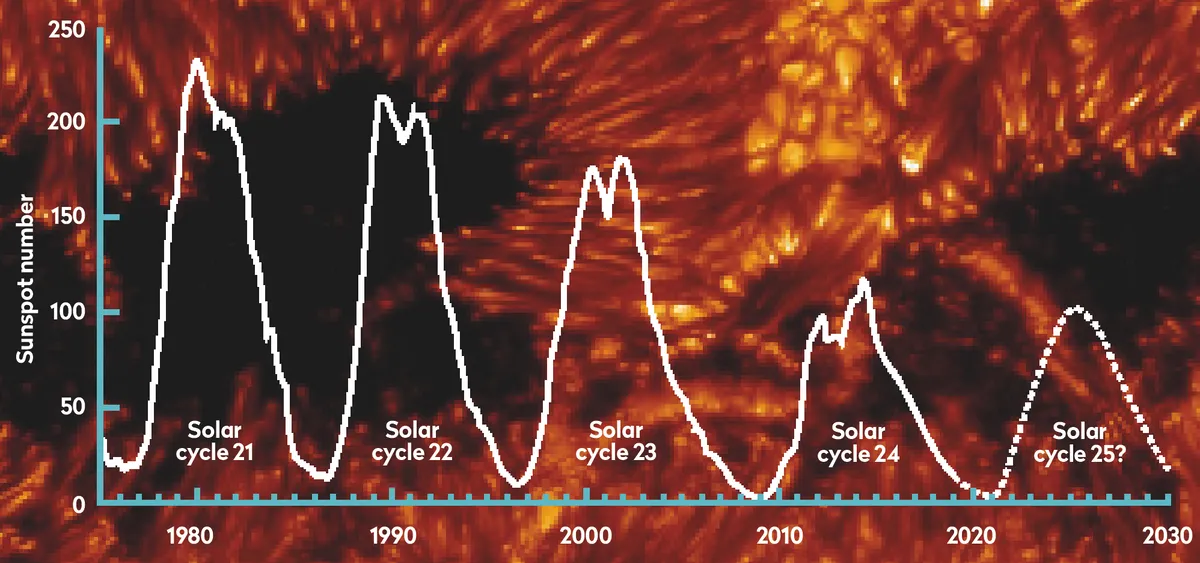

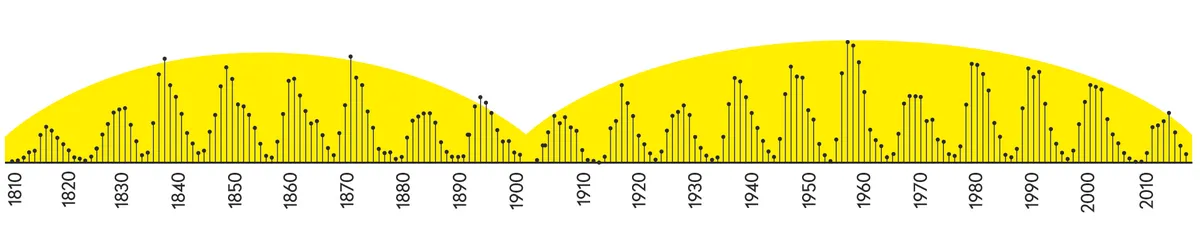

Astronomers track solar activity using a value called the sunspot number, which takes into account not just the number of individual spots, but how they are grouped together.

“We’re currently in Solar Cycle 25, which is the25th cycle since consistent records began in 1755, when extensive sunspot observations started,” says Yardley.

Not all solar cycles are the same

Solar cycles have been far from consistent.

Some solar cycles are as short as eight years between minima, others stretched out to 14 years.

Solar Cycle 19 reached an all-time high sunspot number of 285 in one day in March 1958, while historical records suggest there may have been virtually no sunspots seen between 1645 and 1715.

Since the 1980s, though, solar activity has been decreasing, with sunspot numbers dropping around 20% every cycle.

Predicting Solar Cycle 25

The previous cycle, Solar Cycle 24, was the lowest in a century and many astronomers predicted our current round would follow the trend.

“In April 2019, the Solar Cycle Prediction Panel met and suggested that the current cycle would be weaker than average, very similar to the previous solar cycle,” says Yardley.

The panel was made up of solar experts from around the world, who used various methods to predict what our Sun would do in the coming years.

Previously, the most reliable predictors have been those based on our understanding of the physical processes going on within the Sun.

“Solar minimum was predicted to occur between October 2019 and October 2020, with solar maximum being reached around July 2025, plus or minus six months, with a peak sunspot number of 115,” says Yardley.

That would make it one of the weakest on record.

However, not everyone was as convinced things would be so quiet.

At the same time, another group was looking at a new way of measuring the cycle, one that predicted the Sun could be heading for one of the most active cycles ever seen.

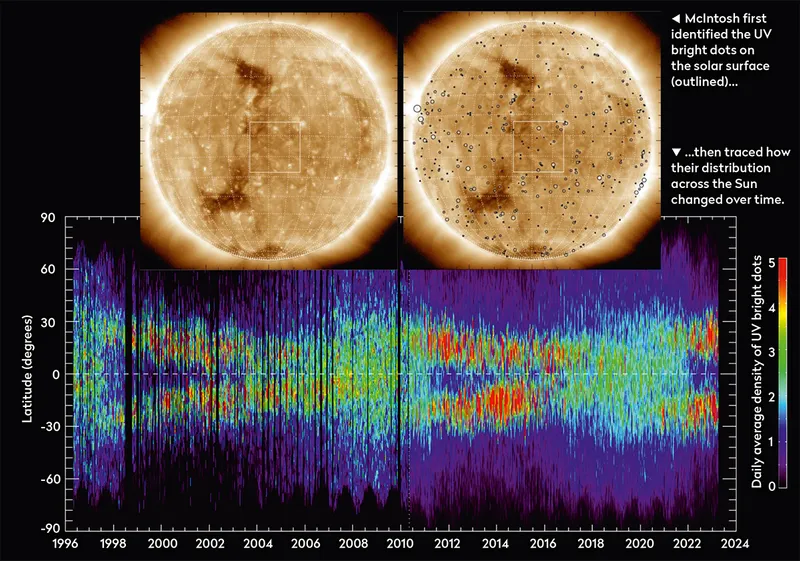

“A decade ago, we identified that the Sun did something really weird,” says Scott McIntosh from the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado.

He and his colleagues have spent the last decade tracking the solar cycle not by looking at sunspots, but at much smaller spots that shine brightly at ultraviolet wavelengths.

“They start at high latitude, around 55°, almost like clockwork every 22 years, and they take 19 years

to get to the equator,” explains McIntosh.

There are normally several bands of these spots drifting their way towards the equator from either side at any one time.

When a north-moving and a south-moving band finally meet at the equator, the magnetic fields which cause them cancel each other out and vanish in what’s known as a terminator event.

“When that happens, the bands at higher latitudes now mark out where sunspots will begin to appear,” says McIntosh.

The precise physical connection between these observed events is unclear, but as sunspots occur when the Sun’s magnetic field is out of balance, it would make sense that these terminator events could unbalance the scales enough to bring them about.

The ultraviolet bright bands don’t move at a steady, uniform speed, so the exact time they take to drift down varies, but this usually means sunspots appear around 30° to 40° latitude.

However, what really seems to matter when it comes to the solar cycle is how long it takes the terminator event to occur.

“The longer the delay in the terminator event at the equator, the more it eats into the development time of the next cycle,” says McIntosh.

“So if that separation is long, it means that the next cycle is weak. If the separation is short, activity would be high because you’re giving the next cycle more time to grow.”

In 2019, McIntosh and his colleagues looked at the bright spots and predicted a sunspot number of around 233, making it one of the most active on record.

When the terminator event arrived in December 2021, they revised this prediction down to a more conservative 185, but this was still considerably higher than most other predictions.

Problems with solar cycle predictions

One of the biggest problems in predicting the solar cycle is that although solar astronomers know the ‘flipping’ magnetic field causes the cycle, they don’t know what causes the poles to flip, or even fully understand the process which generates the field in the first place.

“We call the Sun the ‘destroyer of scientific models’,” quips McIntosh. “You think you’ve understood it and then five minutes later, you haven’t.”

The most recent best theory is that the motions of the Sun’s rotating core create currents that generate the fields.

But how this process works is still strongly debated, and conflicting predictions such as these are a golden opportunity to gain more insight into what’s truly happening.

Solar Cycle 25

So, would Solar Cycle 25 see an all-time low in activity, or a record-breaking high? We are now racing towards the solar maximum, and the verdict is that Solar Cycle 25 is… average.

In May, the average monthly sunspot number recorded was around 138.

While significantly higher than the predicted value of 75, and 40 to 50% larger than at a similar time through Solar Cycle 24, it’s not on track to meet the heady heights of the most active cycles on record.

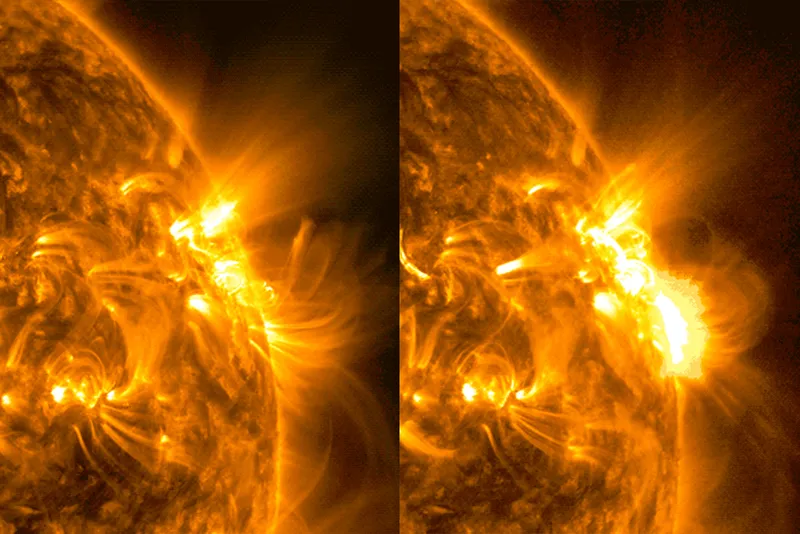

That doesn’t mean the Sun looks dull at the moment. Quite the opposite.

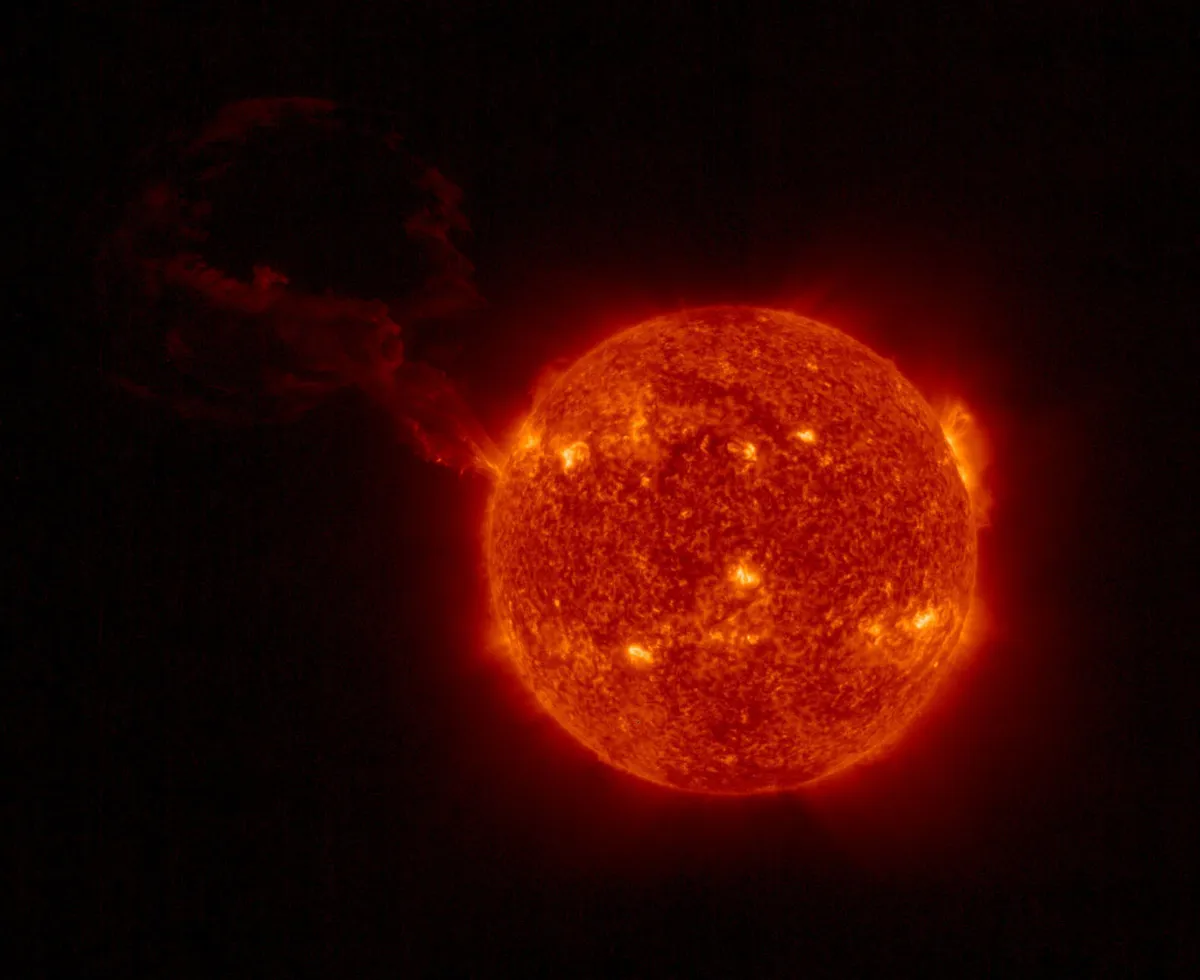

As well as sunspots, there have been several eye-catching loops of solar material, known as prominences.

There were also more solar flares in 2022 than even at the peak of the previous cycle, several of which have been the most energetic, X-class flares.

All of this suggests that solar maximum could be heading our way much earlier than initial forecasts, sometime in 2024 or perhaps even by the end of 2023.

Does this mean the solar predictors need to throw out their models and go back to the drawing board?

Perhaps not, as most initial predictions were madea little prematurely, before the previous cycle had fully ended.

“The Sun ramping up much faster than forecast maybe isn’t surprising in hindsight, given that solar minimum occurred near the beginning of the predicted range, in December 2019,” says Yardley.

But one thing that both teams of solar astronomers agree on is that if we truly want to understand our star, then we really need to be able to get a broader look at the Sun.

“Previous studies have hoped they would find something between 30˚ and 35˚ latitude because that’s where the sunspots appear,” says McIntosh.

“But what if the pattern actually extends back to higher latitudes? 55˚ might be the place to go. Or around the poles.”

Studying the Sun up close

The poles are where the magnetic field lines converge and become highly concentrated, making them key areas to understanding the magnetic field.

Unfortunately, we can only glimpse the region at an oblique angle, when the Sun tilts towards Earth by around 7°.

To get a better view, you need to get out of the plane of the Solar System and look down from above.

“During its extended mission, the orbit of ESA and NASA’s Solar Orbiter will become increasingly inclined out of the ecliptic in order to image the polar regions for the first time,” explains Yardley.

“These observations could provide additional insight into the inner workings of our star, improving predictions of future cycles.”

It will take Solar Orbiter many years and multiple planetary fly-bys to raise its incline, and even then its orbit will only be inclined by around 33˚ from the plane of the Solar System.

Any better view will be up to a future mission.

“Our community is looking at opportunities for the next flagship-class missions,” says McIntosh. “We need to plot a mission to the poles, to characterise the flows there and look for where the magnetic field forms and why.”

Until then, though, there’s really only one thing solar astronomers can do.

“We will have to be patient,” says Yardley. “And take a watch-and-wait approach to see when solar maximum will occur and how strong it will be!”

This article originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.