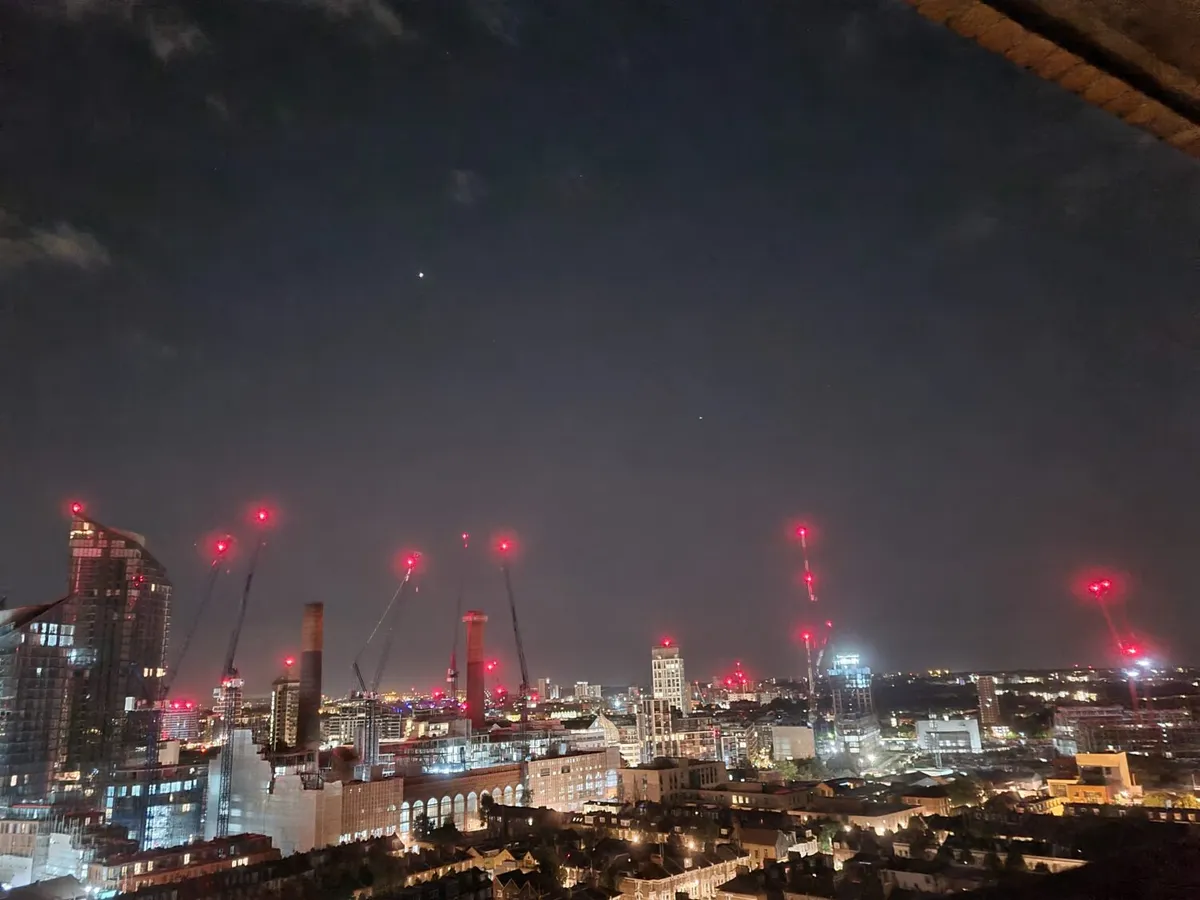

There’s one night every year when it’s guaranteed that people will be lured away from their TVs and out into the darkness, and that’s 5 November – Bonfire Night.

As darkness falls some families head into their gardens to light a handful of fireworks, while others join the crowds in parks or sports grounds to bask in the glow of a bonfire and watch a large display.

But watching fireworks is seeing only half of the display available because, as we’ll show here, if the sky is clear on Bonfire Night there are many other beautiful things to see in the night sky too, and during lulls in the action you just have to raise your eyes to enjoy seeing some celestial wonders.

For more autumnal astronomy, read our guide to Halloween stargazing, or find out what to see in the night sky at autumn.

For more general advice, read our guide on how to stargaze.

How to stargaze on Bonfire Night

What will you need to stargaze on Bonfire Night? First of all you’ll need to dress appropriately – and by that we mean warmly, in a jacket, hat and gloves.

If you want to take this article outside to help you find the targets, don't forget to turn your phone's screen red to preserve your dark-adapted vision.

Although all the targets we’ve suggested observing here are visible to the naked eye, it’s a good idea to take a pair of binoculars with you if you have them.

They’ll make the bright objects even clearer, enhance their colours, and help you find the fainter objects if it’s very hazy.

And if you’re worried about even trying to stargaze on a night when there’s even more smoke and murk around than usual, don’t be: it’s always good to get out under the stars, and clear nights are so rare you should use every one you can.

There’s also something special about stargazing on Bonfire Night, as childhood memories tap you on the shoulder.

I had my first sighting of Halley’s Comet on Bonfire Night in 1985 – peering into my binoculars with more smoke swirling around me than on a battlefield – when it was little more than an out-of-focus star close to the Hyades.

Now that you're ready, here’s what to watch out for during Bonfire Night 2021 as the evening progresses.

Stargazing on Bonfire Night, 5 November 2021

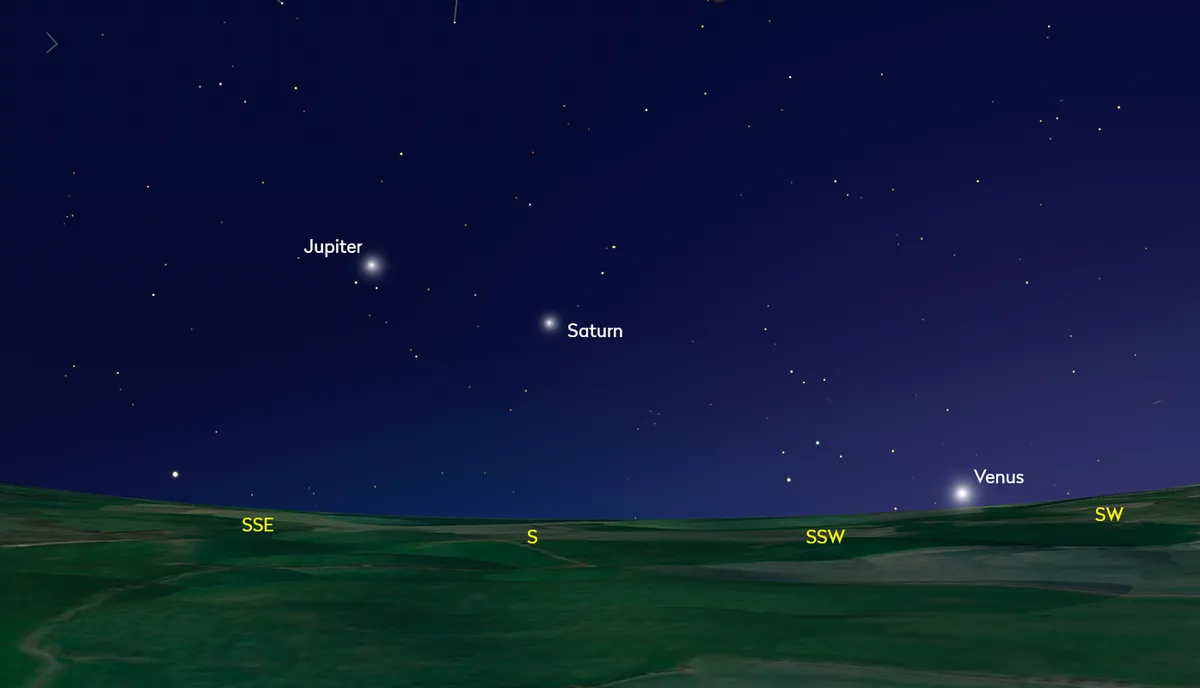

6pm: Jupiter, Saturn, Venus

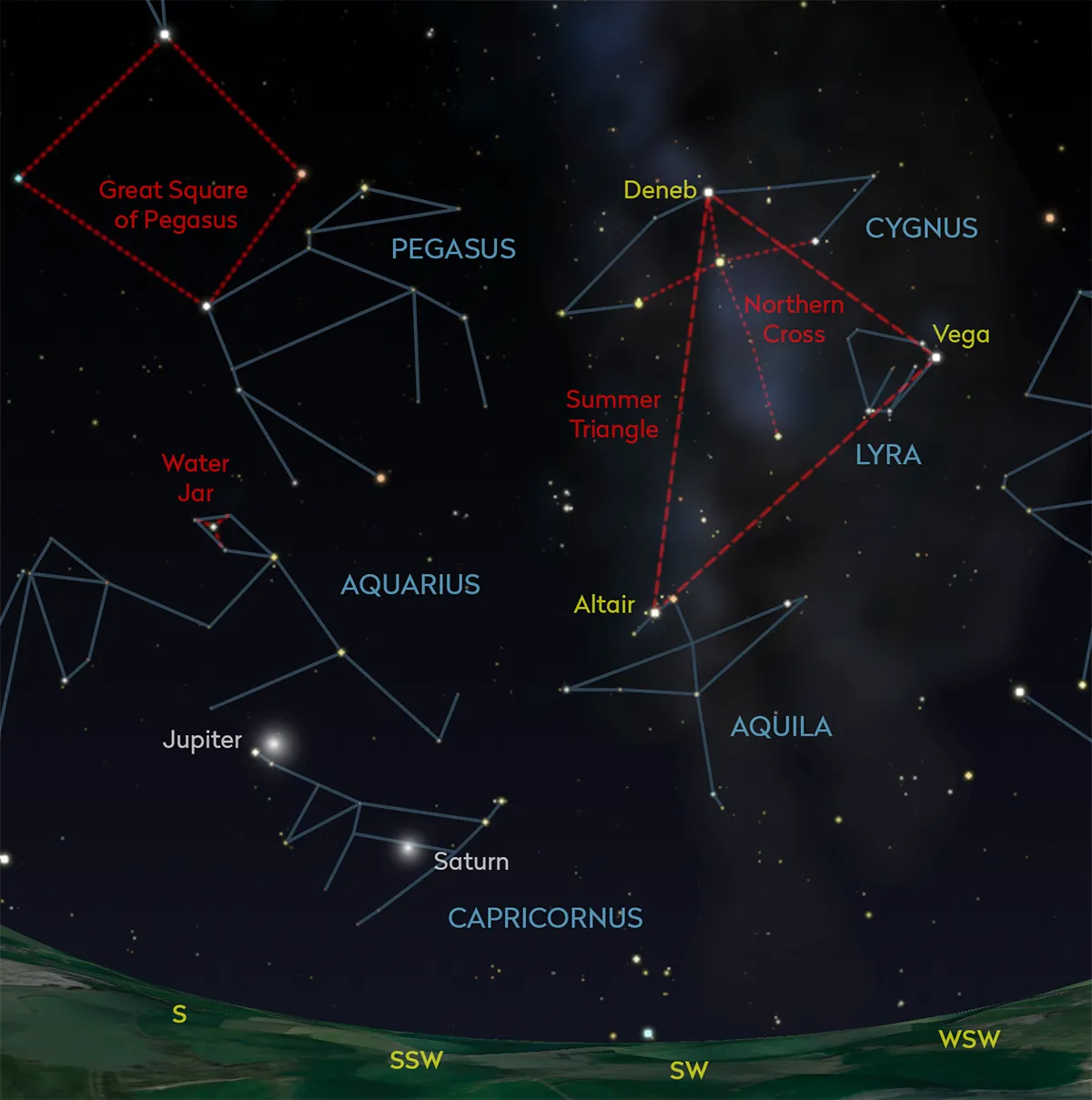

With the first fireworks of the evening crackling up into the sky, you’ll see two bright stars shining close together low in the south.

These are actually the planets Jupiter and Saturn, currently appearing close together in the sky, but actually separated in space – and from us – by enormous distances.

Jupiter, on the left and the brighter of the two, is the largest world in our Solar System, a bloated ball of gases and liquids so huge it could swallow 1,000 Earths with room to spare.

NASA’s Juno mission is sending back breathtaking images of Jupiter’s swirling cloud belts and psychedelic-looking storm systems, all of which are available to view online for free by visiting the Juno mission website.

Looking like a yellow-hued star to blue-white Jupiter’s lower right, fainter Saturn is, of course, famous for its rings, but these can only be seen through a telescope.

If you have a clear view to the southwest you might be able to see another planet.

Venus will be shining very low in the sky in that direction, a Bonfire Night ‘Evening Star’, but just be aware that any trees or houses on your skyline in that direction will hide it from your view.

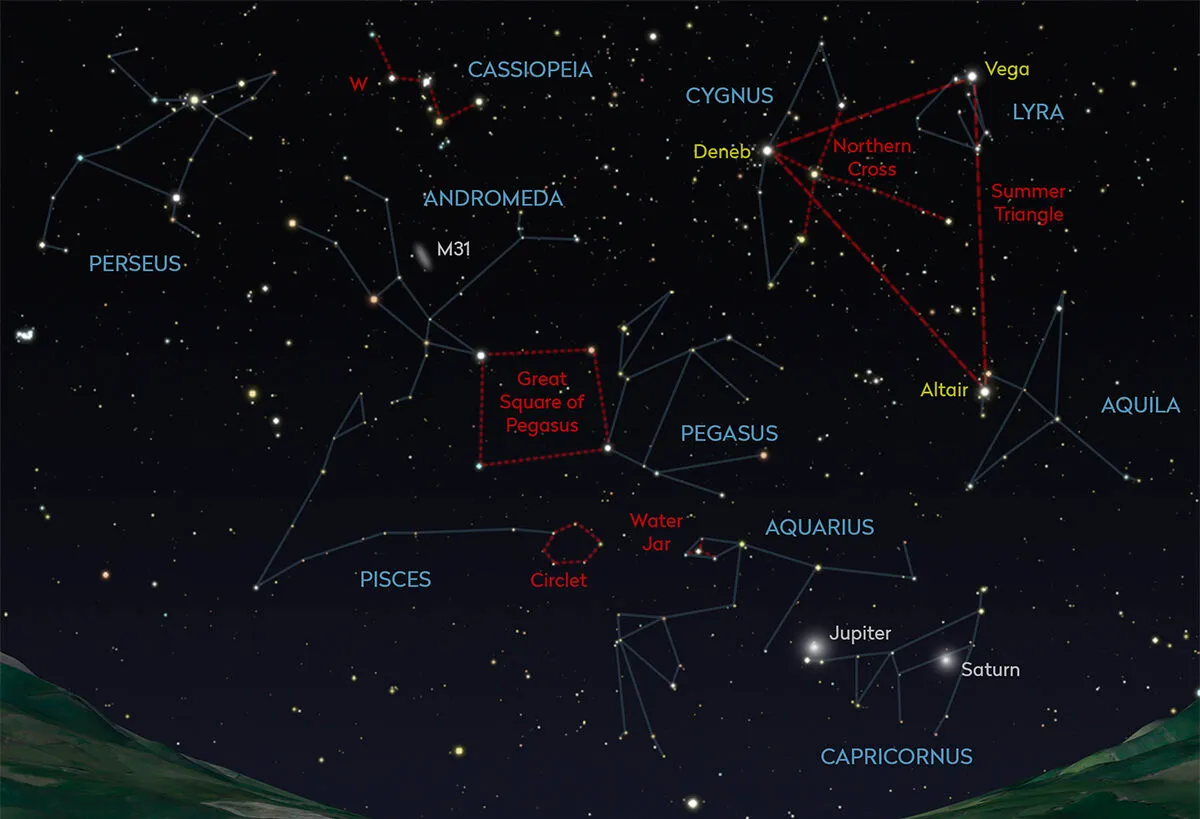

7pm: Summer Triangle, Cassiopeia, Andromeda Galaxy, Milky Way

By now your eyes will have ‘dark adapted’ enough that even with the red glare of rockets bursting in the air above your head you’ll be able to see more objects in the night sky.

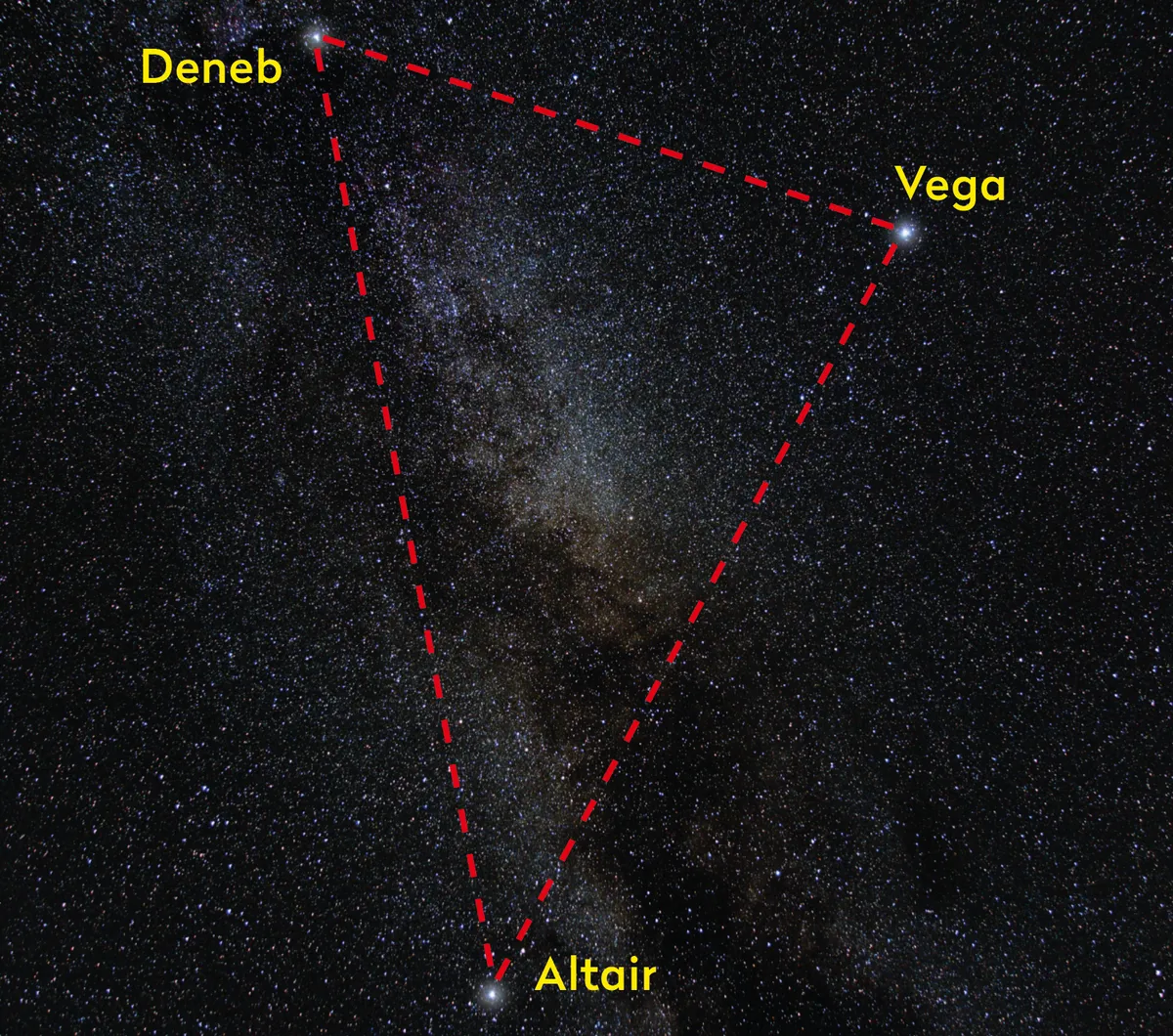

One of the first you’ll notice is a striking triangle of three bright blue-white stars almost directly above Jupiter and Saturn.

This isn’t a constellation, it’s an asterism – an obvious pattern of stars – called the Summer Triangle, still visible even though it’s November.

Its three stars are Deneb (Alpha (α) Cygni), Vega (Alpha (α) Lyrae) and Altair (Alpha (α) Aquilae), the brightest stars in the constellations of Cygnus, the Swan, Lyra, the Lyre and Aquila, the Eagle, respectively.

Having found the Summer Triangle, look high to the southeast and you’ll spot a ‘W’ of stars.

This is the constellation of Cassiopeia, the Queen, and you can use it as a pointer to help you locate something very special indeed – M31, the Andromeda Galaxy.

For help locating the galaxy, read our guide on how to see the Andromeda Galaxy.

M31 is a group of billions and billions of stars, so far away their faint light has taken more than two million years to reach us.

Long exposure photos taken through telescopes reveal M31 to be a lens-shaped cloud of glittering stars streaked with dark dust lanes, but to the naked eye it looks like a small smudge.

In fact, if your Bonfire Night sky is smoky you might need a pair of binoculars to see it, but as with many astronomical objects it’s knowing what that smudge is that makes seeing it so exciting.

If your sky is clear, and if you aren’t surrounded by light pollution, you might also glimpse the misty trail of the Milky Way rising up from the western horizon.

Arching overhead, this is the combined light of billions of stars within our own Galaxy, seen from within, and as you look at it you might even be reminded of smoke rising from a distant bonfire…

7.30pm: Taurus, Pleiades and Hyades

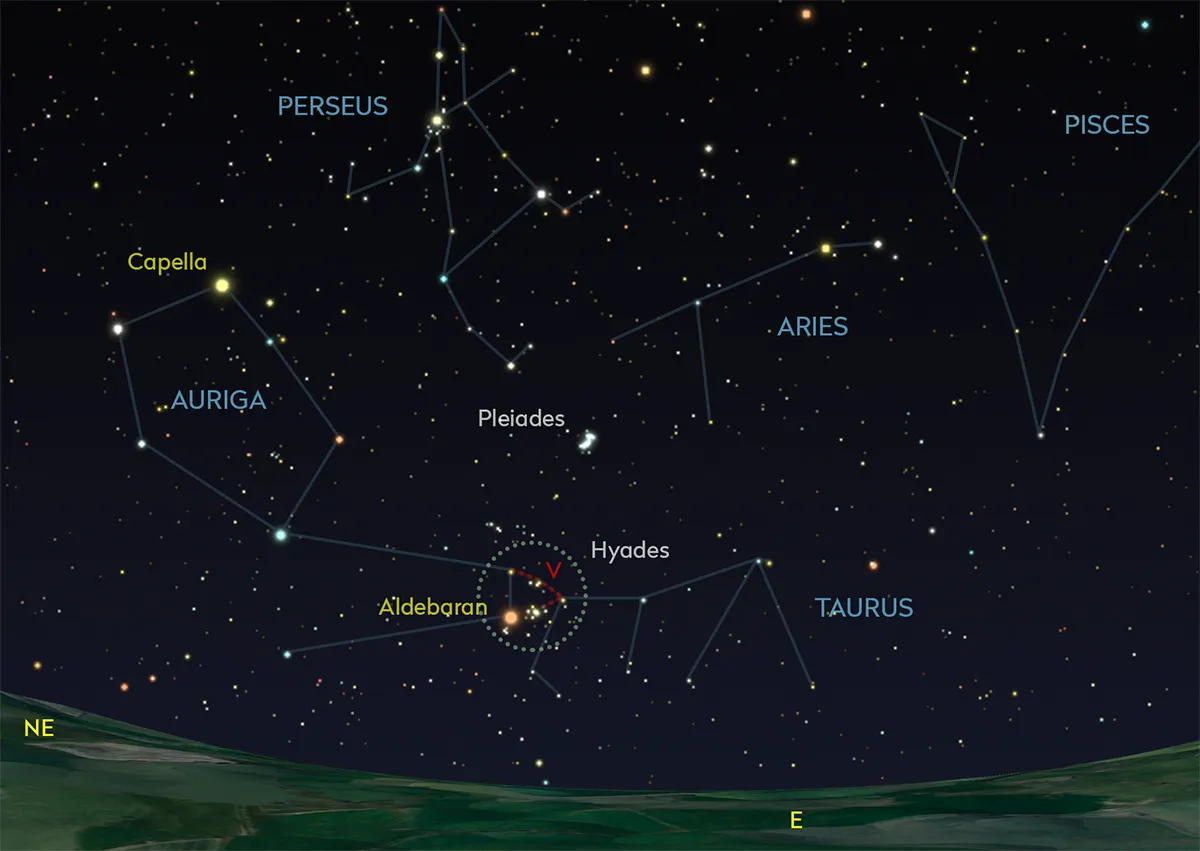

By mid-evening the constellation of Taurus, the Bull will be rising in the east.

It’s easy to spot because it is dominated by two striking star clusters that are both obvious to the naked eye.

The most noticeable is the Pleiades star cluster.

Look to the east mid-evening and you’ll see a small knot of ice-blue stars shining low in the eastern sky, perhaps the size of your thumbnail held out at arm’s length – that’s the Pleiades.

This celestial celebrity of a star cluster contains hundreds of stars, but it’s known widely across the world as ‘The Seven Sisters’ because its seven brightest members can be seen with the naked eye, looking like a tiny, squashed-up version of the Plough.

If you look halfway between the eastern horizon and the Pleiades you’ll see a strikingly orange star.

This is Aldebaran (Alpha (α) Tauri), the ‘Eye of the Bull’, and if your sky is dark enough you’ll see that it marks the end of one side of a ‘V’ of stars lying on its side.

This arrowhead is the Hyades star cluster, a favourite of many observers. Much larger than the neighbouring Pleiades, the Hyades represents the horns of Taurus.

8pm: The Plough, Mizar and Alcor, Polaris

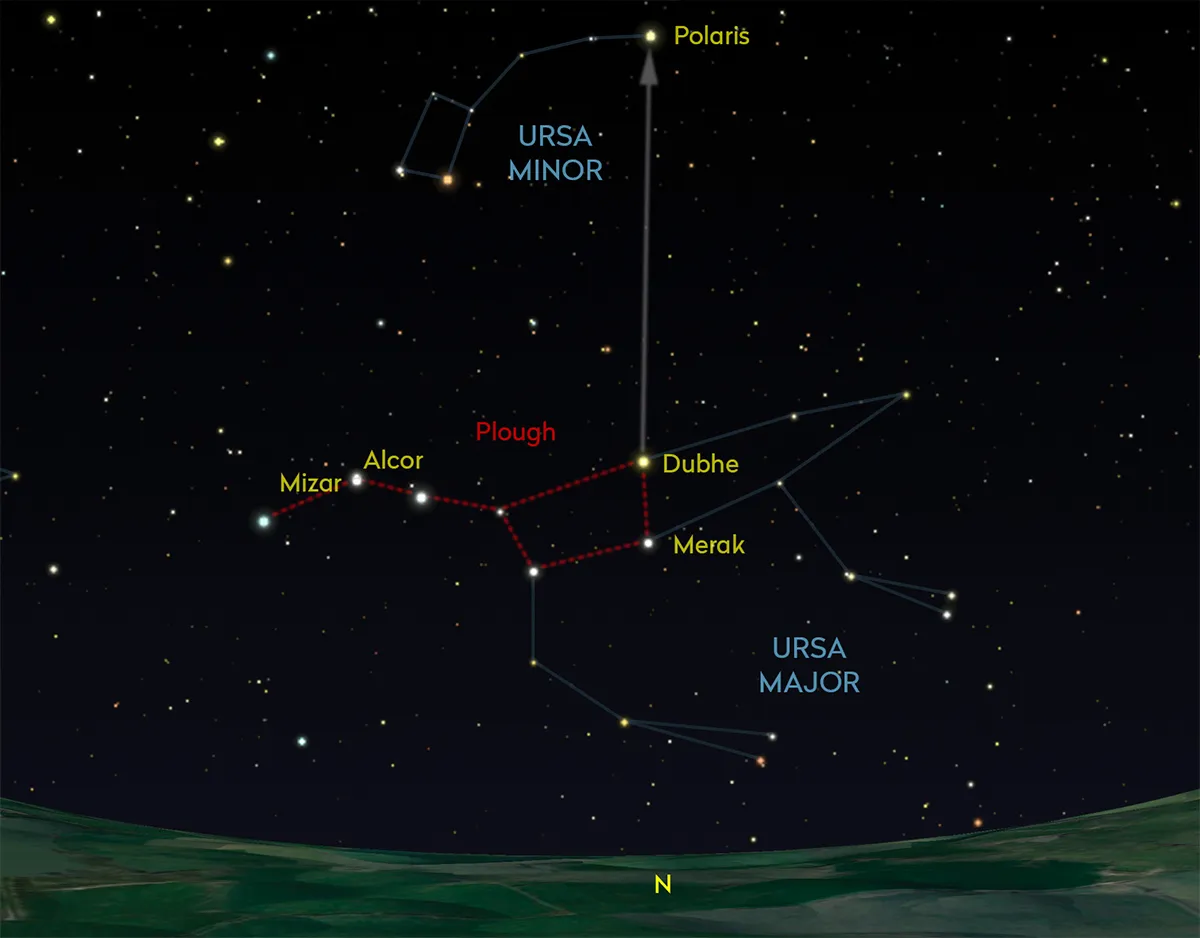

By now the Bonfire Night festivities will be well underway and if you look to the north as the sparkly trails of rockets swoosh up into the sky, you’ll see the stars of the Plough (or Big Dipper) shining above the horizon.

November is a great time of year to see this asterism – which is part of the larger constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear – because during the evening its orientation means it looks exactly like the famous ‘Saucepan’ many people affectionately call it.

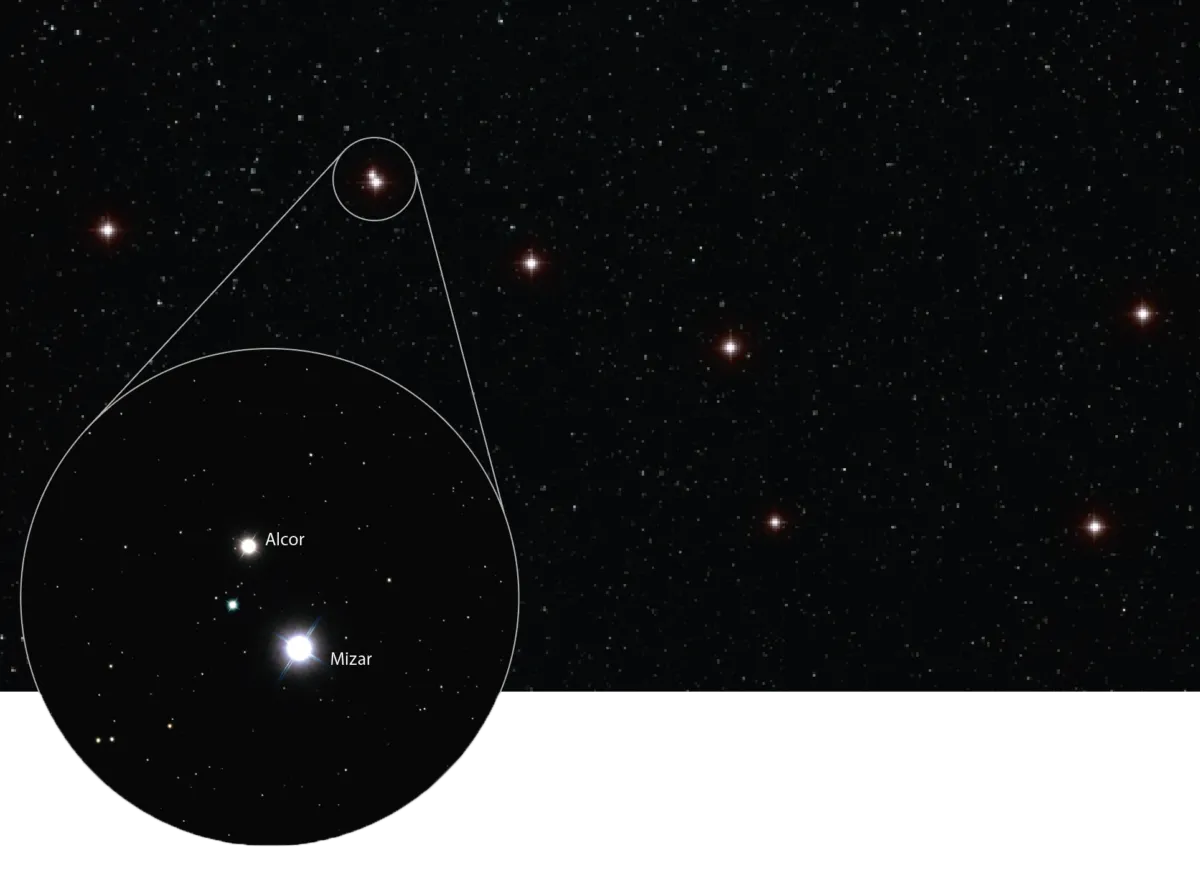

If you have good eyesight you will be able to see that the star in the middle of the Plough’s handle is actually two stars close together. This famous double star consists of Mizar and Alcor.

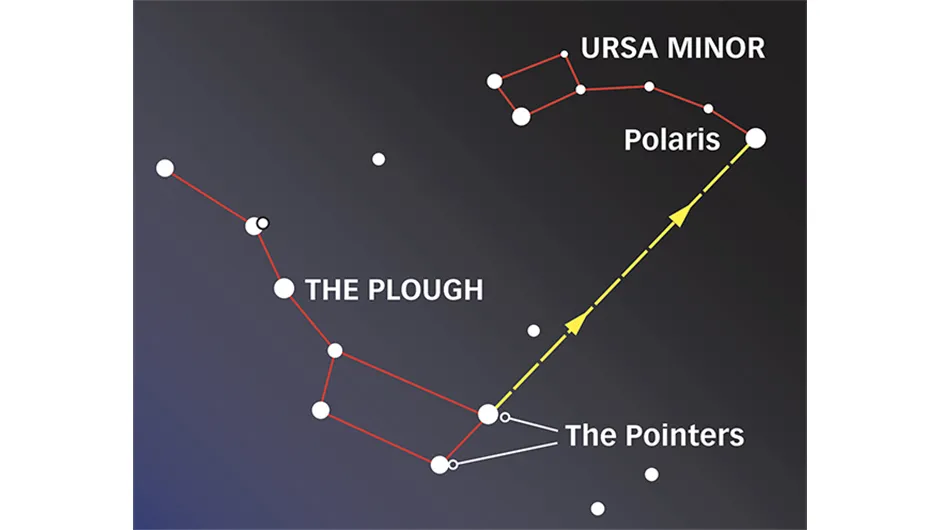

The Plough isn’t just an attractive asterism though; it can be used to find the most famous star in the sky.

Its two right-hand stars known as ‘The Pointers’ point directly towards Polaris (Alpha (α) Ursae Minoris), the Pole Star.

Many people grow up believing that the Pole Star is the brightest star in the sky, but it’s actually only the 48th brightest!

Its fame comes from the fact that it just happens to lie directly in line with Earth’s polar axis, so it remains still through the night while every other star, planet and object in the sky appears to whirl around it.

For help locating it, read our guide on how to find the North Star.

10pm: Orion rises and the sky has changed

By late evening the firework displays will be drawing to a close, but before heading back indoors take a last look at the sky.

You will notice – perhaps for the first time – that it has changed since you came out: Jupiter and Saturn have dropped behind the horizon, and the Summer Triangle is lower too.

The Plough isn’t parallel to the skyline any more, but has pitched up slightly so it’s balancing on the end of its handle.

The Pleiades and Hyades clusters will be higher in the sky too.

Finally, as the smoke of dozens of bonfires begins to clear you’ll see a striking pattern of stars rising in the east: the constellation Orion, the Hunter, with red Betelgeuseshining at his right shoulder and his famous Belt of three blue-white ice-chip stars pulled across his waist.

Seeing Orion climbing up from behind the eastern horizon late on a chilly autumn night is a sure sign that winter is coming.

Keep observing

Bonfire Night is popular with many people, because it gives them an opportunity to see coloured lights in the sky, but you may be standing there unaware that nature is putting on an even more beautiful display of celestial lights – one that takes place every night.

For amateur astronomers who can look up and see not just rockets but stars exploding – with misty-armed galaxies turning like Catherine wheels, and shooting stars leaving trails of sparks across the heavens – every night is a cosmic Bonfire Night!

This guide originally appeared in the November 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.