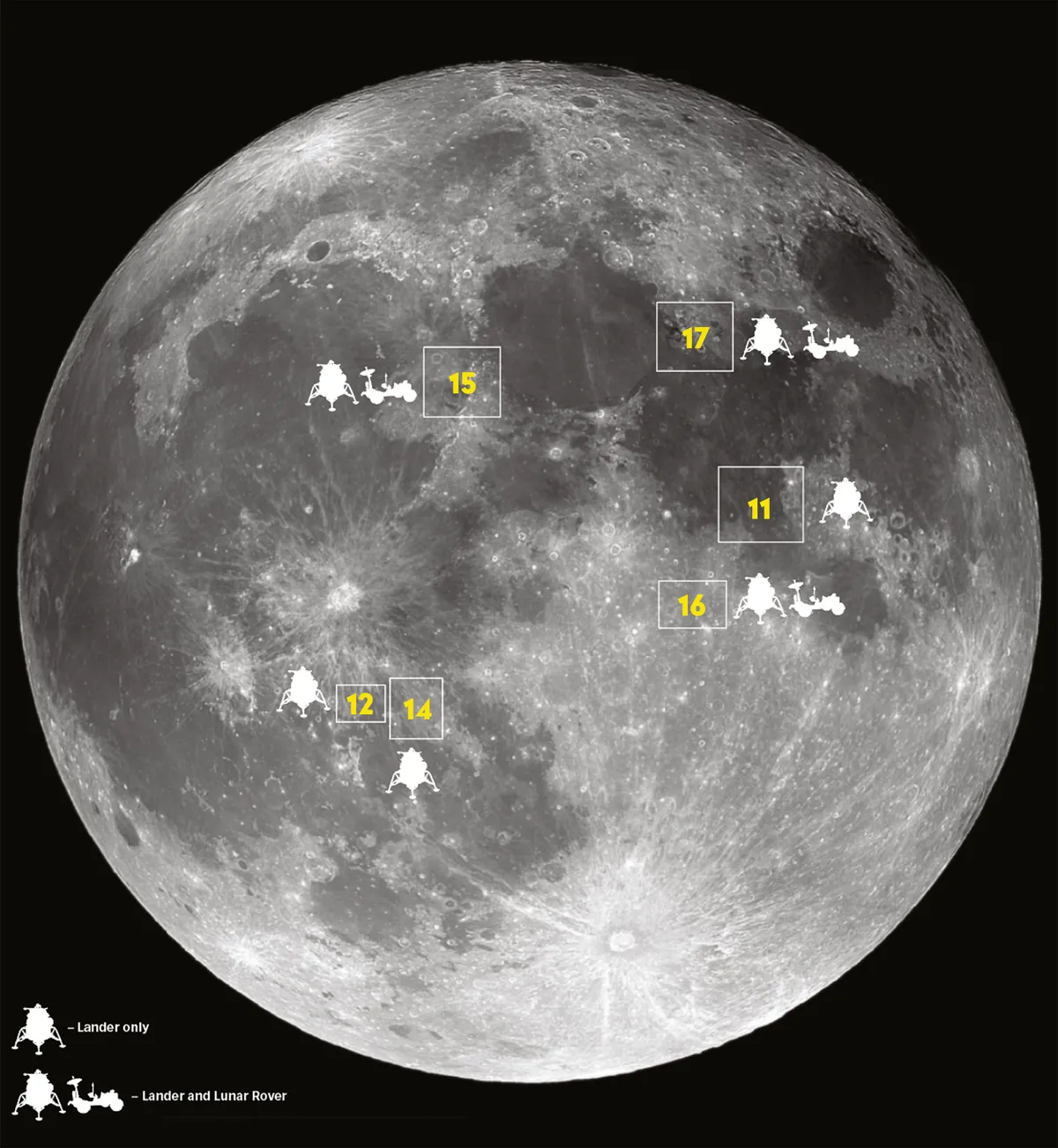

Did you know that it is possible to see all 6 Apollo landing sites on the Moon? In this guide we'll show you how to find them and what you can see through your telescope.

It should be pointed out that it's impossible to see the hardware that was left behind, but the areas where the Apollo missions landed are rich in sights that can be studied using simple instruments.

A pair of 10x50 binoculars will get you familiar with the general locations of the Apollo landing sites on the Moon and put them into a geographical context.

To get more detail and see the Apollo moonlanding sites properly you’ll need a telescope, but even the smallest instrument can provide a glimpse of some of the features we mention below.

A neutral density filter is also a worthwhile investment when observing the Moon. This makes a great difference if you are observing close to a bright full Moonbecause it brings out detail masked by the glare.

For more advice, read our guide on how to observe the Moon, our pick of the best features to see on the Moon or our guide to lunar maria.

And for moonrise times and phases delivered directly to your email inbox every week, sign up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter.

Apollo landing sites on the Moon: what to see

Below is a guide to each of the Apollo landing sites on the Moon and what to see through your telescope once you've found them.

Apollo 11

- Landing site: Sea of Tranquillity

- Lunar Landing: 20 July 1969 at 20:18 GMT

- Lunar Lift off: 21 July 1969 at 17:54 GMT

- Crew: Neil Armstrong (cdr); Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin; Michael Collins

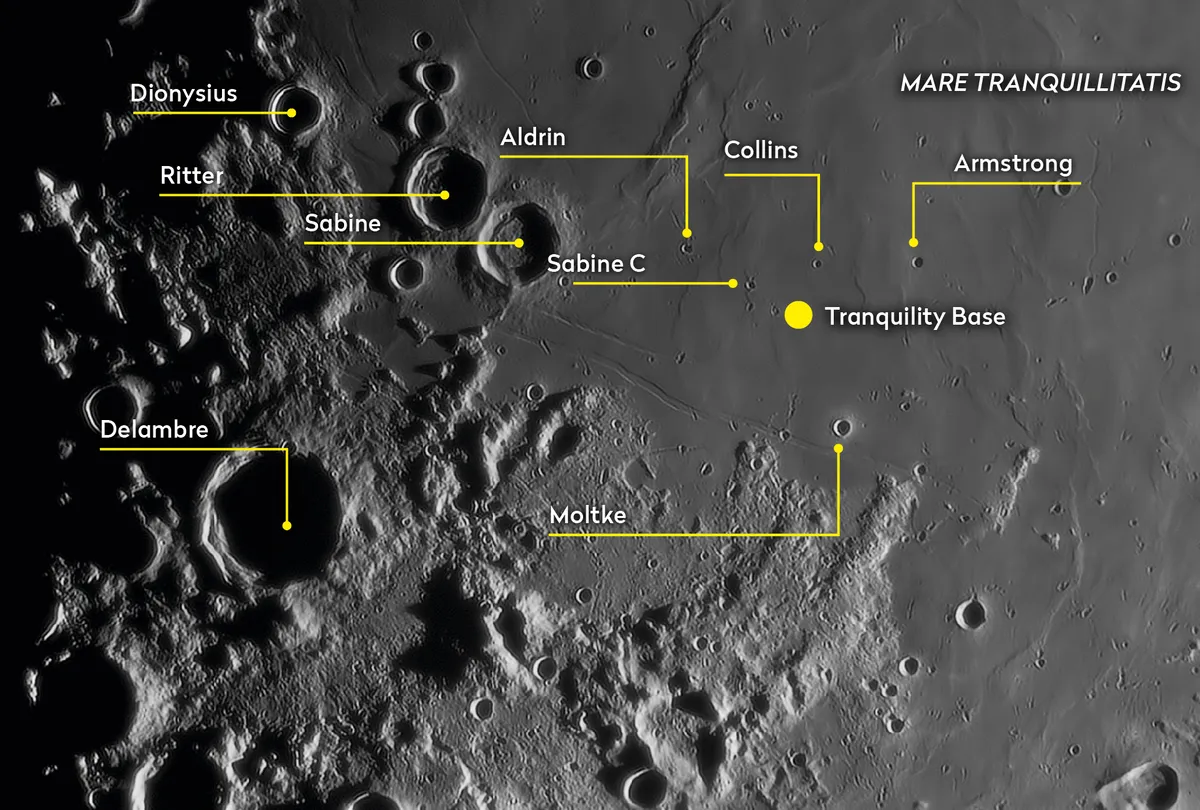

We’ll begin our tour with the Apollo 11 mission, which landed in the south of the Sea of Tranquillity.

The prime concern on this journey into the unknown was safety, so mission planners chose what they thought was the smoothest region to land on using lunar satellite data and ground-based observations, some of which were carried out by Patrick Moore.

Almost 20kg (44lb) of lunar material was returned, and Neil Armstrong became famous as the first person to set foot on the Moon’s surface, with Aldrin the second. The historic event was watched by millions worldwide on TV.

The main features visible at this site are the craters: tiny Moltke south of the landing site, which is now called Statio Tranquilitatis, and the larger Sabine and Ritter.

The Lunar Reconaissance Orbiter even found evidence of an underground cave on the Moon near the Apollo 11 landing site.

When the view is good, try using high magnifications to spot the 3 tiny craters that are named after the Apollo 11 crew.

These lie in an east to west line just north of the landing site. Watch from 6 to 9 days after new Moon and from 4 to 6 days after full for the best views.

For more advice, read our complete guide on how to see the Apollo 11 moonlanding site.

Apollo 12

- Landing site: Sea of Storms

- Lunar Landing: 19 Nov 1969 at 06:55 GMT

- Lunar Lift off: 20 Nov 1969 at 14:26 GMT

- Crew: Charles (Pete) Conrad (cdr); Alan Bean; Richard Gordon

Landing in a safe, relatively flat area in the Sea of Storms, Apollo 12 proved that Apollo 11 wasn’t a fluke.

By touching down next to the Surveyor 3 lander, which had been on the Moon for 2 years, it also showed that pinpoint landings with the Lander could be achieved.

Several parts of Surveyor 3 were salvaged by the astronauts and brought back to Earth, the ALSEP (Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package) was deployed and the crew spent over 31 hours exploring the surface.

Apollo 12 visited the far southeastern edge of the Oceanus Procellarum. Near the landing site lies the crater Lansberg with its terraced walls and central peak.

To the southwest, Montes Riphaeus offers interesting views, while craterlets, such as Fra Mauro B, are small bowl-shaped craters that stand scrutiny well.

When you view this region at full Moon you’ll be able to see the faint wisps of rays that can be traced back to the large crater of Copernicus.

Apollo 14

- Landing site: Fra Mauro

- Lunar Landing: 5 February 1971 at 09:17 GMT

- Lunar Lift off: 6 February 1971 at 18:48 GMT

- Crew: Alan Shepard (cdr); Edgar Mitchell; Stuart Roosa

Following the almost disastrous failure of Apollo 13, NASA wanted to show that it could still go to the Moon and come back safely.

The Apollo 14 landing site in the Fra Mauro region, with its extensive geological formations associated with the Imbrium Basin, allowed astronauts to collect and return more interesting samples of rock for analysis.

Commander Alan Shepard was the only astronaut from the Mercury 7 flights to walk on the Moon. He surprised everyone by playing a round of golf on it.

This mission touched down in the hills just to the north of the main walled plain that makes up the feature.

Fra Mauro has the craters Bonpland and Parry to its south and southeast respectively, and there are more Fra Mauro craterlets scattered over the region.

Both the Apollo 12 and 14 sites are best seen between 8 to 10 days after new Moon and 6 to 8 days after full phase to bring out these craters.

Apollo 15

Apollo 15 landed in a much more hilly area, among the Apennine Mountains, close to the site of Mons Hadley.

Apollo 15’s landing site was geologically very interesting – the nearby Hadley Rille was a prime target for exploration.

This was also the first flight to carry the Lunar Rover Vehicle and improved spacesuits enabled the crew to stay on the surface for almost 67 hours.

The Command Module studied the Moon from orbit, while on the surface, commander Scott performed a simple experiment suggested by Galileo: he dropped a feather and a hammer and they landed at the same time.

This whole area is rich in detail: as the lunar terminator sweeps across the region look out for isolated peaks jutting out from the shadows as the Sun begins to illuminate the area.

A large telescope, high powers and good seeing are needed to view Hadley Rille itself, but it’s worth pursuing in the knowledge that the Apollo 15 astronauts drove the first Lunar Rover vehicle in this region.

View the area a couple of days after first quarter and from 4 to 6 days after full Moon.

Apollo 16

- Landing site: Descartes Highlands

- Lunar Landing: 21 April 1972 at 02:23 GMT

- Lunar Lift off: 24 April 1972 at 01:26 GMT

- Crew: John Young (cdr); Charles Duke Jr; Thomas Mattingly II

Apollo 16 experienced rugged terrain when it landed in the Descartes Highlands.

This was the first mission to explore the geologically different highland terrain, which was thought to be older crustal material compared with the younger volcanic maria.

The Rover was used for the second time: it went on 3 excursions notching up 26.7km (16.5 miles) in total.

The crew spent 71 hours on the Moon and collected 96kg (211lb) of material for return to Earth.

On the third and final outing on the surface, Charlie Duke left behind a plastic-encased photograph of his family for posterity.

The Descartes crater isn’t wonderful itself, but it does have a small, brighter craterlet on its side and a lighter patch of material on its northern wall, pointing the way to the landing site.

On a wider scale lies the crater Kant and the bigger trio of craters Theophilus, Cyrillus and Catherina to the east.

Observe the site about a day either side of first quarter and 4 to 5 days after full Moon.

Apollo 17

The final Apollo mission – Apollo 17 – landed at a site located in the Taurus-Littrow area of the Moon, the dominant features of which are the Taurus Mountains and the crater Littrow.

It was the only mission to carry an actual geologist by profession – Dr Harrison Schmitt.

The landing site was particularly ambitious due to the surrounding hills, but proved worth it when, on the second Rover excursion, the crew discovered orange soil.

A range of rock types were found, including breccias and vesicular basalts, and 115kg (253lb) of samples were brought back to Earth.

This final mission to the Moon spent a total of 75 hours on the surface before Apollo left for good.

The Lunar Lander touched down in a valley that lies roughly between the craters Littrow to the north and Vitruvius to the south, both of which are worth viewing.

Other noteworthy craters nearby include Maraldi and Fabroni. The area is best seen 5 to 6 days after new Moon and 2 to 4 days after full.

5 tips for observing the Apollo landing sites on the Moon

Familiarise yourself

Study the general features of the Moon with binoculars first. Identify the principal landing sites and the geographical regions they lie in so that you can home in on them using a telescope. Make a note of any particular prominent features that may help you find the landing site area.

Get a lunar map

Buy a good guide to the Moon or print out maps from astronomical software to use at the telescope. Charts at several levels of detail will help you focus on the sites, but make sure they aren’t too cluttered with detail, which may confuse you at the eyepiece.

Pay attention to the terminator

Take note of where the terminator lies in relation to the landing site you’re going to observe. Observing at full Moon will generally wash out fine detail but will allow good views of the ray features emanating from craters like Copernicus. Ideally observe a day or two before or after the terminator reaches or leaves the site.

Go for higher magnification

Depending on the viewing conditions, it’s worth pushing the level of magnification just in case you catch that moment of great seeing and glimpse even finer details. These could be small craters or some of the subtle lava flows and rilles near to the landing sites. Using neutral density filters may also help.

Record what you see

Keep a thorough record of your observations, whether you observe visually or have a camera attached to your scope. Lighting conditions on the surface depend on the phase of the Moon. This never repeats itself at exactly the same time each month, so keep revisiting the sites to watch for subtle variations.

Have you observed the Apollo landing sites on the Moon? Let us know how you got on by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This guide originally appeared in the October 2007 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.