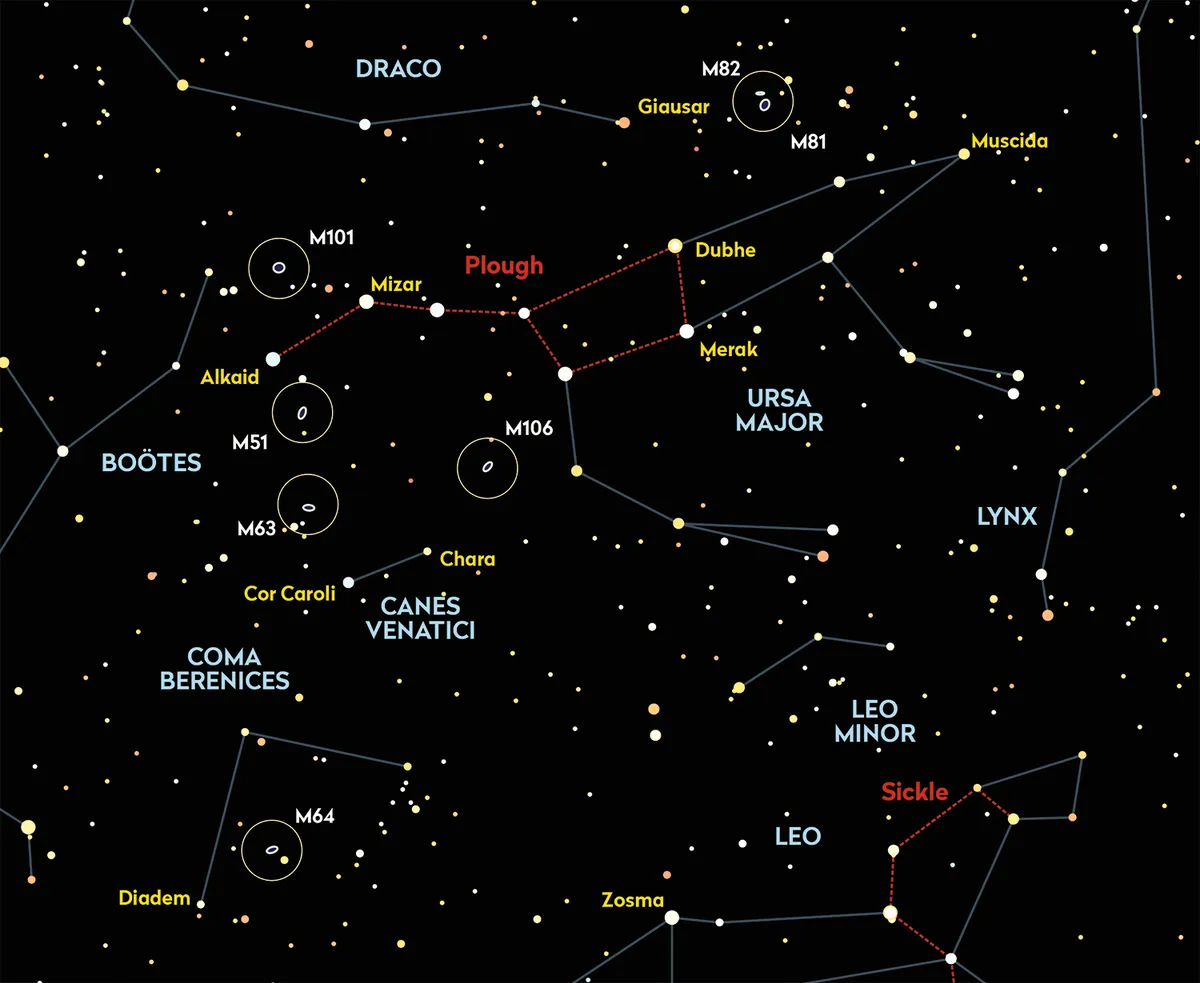

Ursa Major is a great constellation and great area of the sky for observing galaxies, and this is certainly the case come springtime.

Then, the great globe of the heavens rolls on and the brilliant star clusters and nebulae of winter are sinking in the west.

Deep-sky observers turn their attention to the subtler marvels on the rise – the galaxies.

Hence, springtime is often referred to as 'galaxy season' by astronomers, such is the wealth of wonderful galactic beauties visible in the night sky.

In the north, the Great Bear, Ursa Major, and its neighbouring constellations, Canes Venatici and Coma Berenices, are riding high.

A word on light pollution

No object in the sky is more harmed by light pollution than galaxies. The first thing you learn about galaxy observing is: the darker the sky, the better.

Many can be seen in suburban skies, but to see details, to observe anything in most galaxies other than their bright central regions, you’ll need to get to the darkest location you can access.

Whether your skies are bright or dark, however, there are tips that can help you.

Being able to not just see galaxies, but see them well, requires learning a few tricks of the trade to deal with the challenges they present.

We’ll use these tips and tricks tonight as we wander from galaxy to galaxy.

Best telescope for observing galaxies

Any telescope design can work well for observing galaxies, but the larger the lens or mirror, the better.

Galaxies are the dimmest objects we view, and maximum light-gathering power is needed.

You can see many galaxies in 3-inch telescopes, and I’ve had some terrific views with 6- to 8-inch instruments.

If you want to see detail in them, however, not just tick galaxies off an observing list, aperture is the key.

In my experience, a 10-inch telescope is the place to start observing galaxies and 12 inches of aperture is better.

Of course, you shouldn’t buy one so large you’ll be reluctant to use it frequently.

How about a mount for observing galaxies? Unless you plan to do astrophotography, there’s no need to invest in an expensive and heavy equatorial mount.

A simple unpowered Dobsonian altazimuth mount works fine.

No, it won’t track the stars, but it can be used to easily track by hand.

Also, today some inexpensive Dobsonian telescopes do feature tracking and even computerised Go-To pointing.

7 galaxies in and around Ursa Major

Whirlpool Galaxy

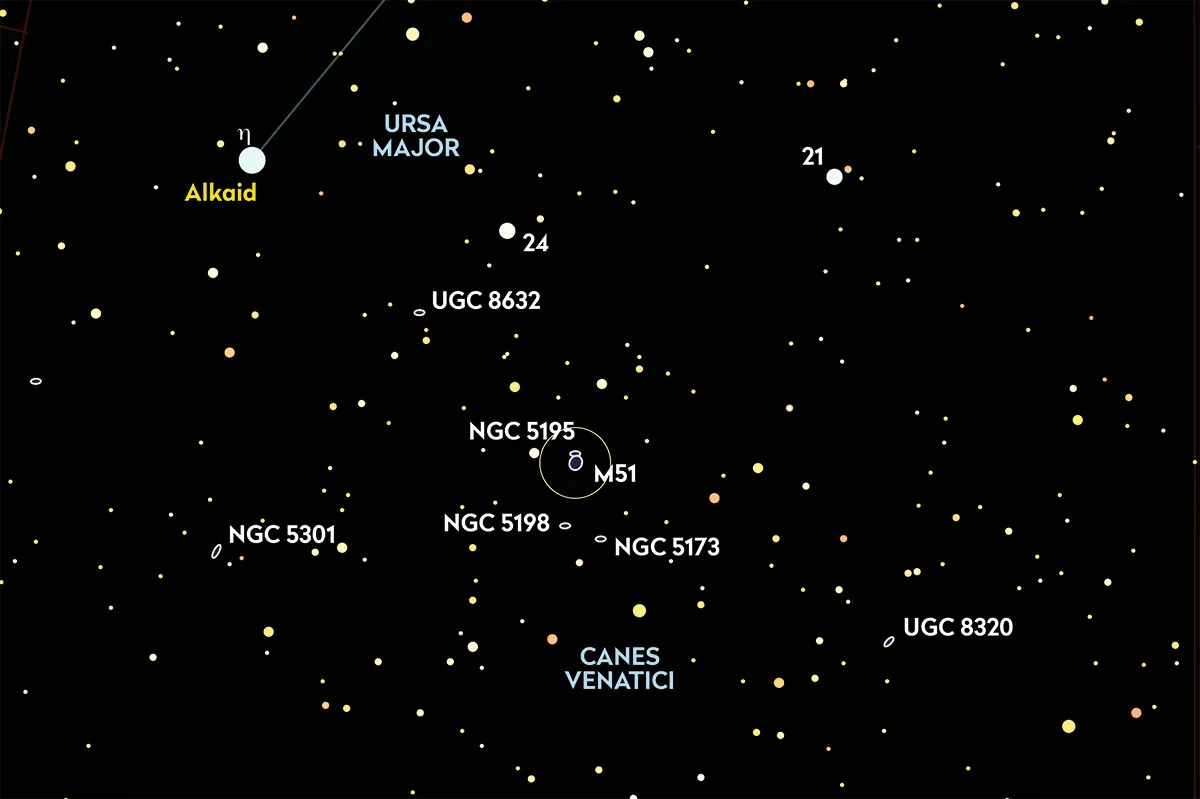

Our first galaxy, M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, is not technically in Ursa Major, but is close to it, in the small constellation Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs.

The galaxy lies only 3.6° southwest of Alkaid, the star at the end of the Plough’s handle.

This is not a difficult object to find, even without the aid of computerised Go-To telescope pointing.

The Whirlpool Galaxy is a face-on spiral galaxy, and that causes problems for the visual observer – its light is spread out across the eyepiece field, making it difficult to see no matter its magnitude.

Luckily, the Whirlpool is small enough at 9.8 x 7.8 arcminutes that its mag. 8.7 light is still fairly concentrated.

What will you see? With a 6-inch reflector from light-polluted suburban skies, I see two blobs, a big one and a small one, the small one being the irregular galaxy NGC 5195 that is interacting with the Whirlpool.

As aperture goes up and the skies get darker, however, this galaxy begins to look like its photos.

With a 12-inch reflector from a southwestern US desert, I can see abundant spiral structure, dark patches and a lane of pulled-off material, the ‘bridge’ connecting the Whirlpool and NGC 5195.

A tip to enhance the M51 experience to is protect your scope and eyes from ambient light.

The light of nearby sources, like porch lights, does as much to harm your eyes’ dark adaptation and spoil the view as the sky’s overall light pollution

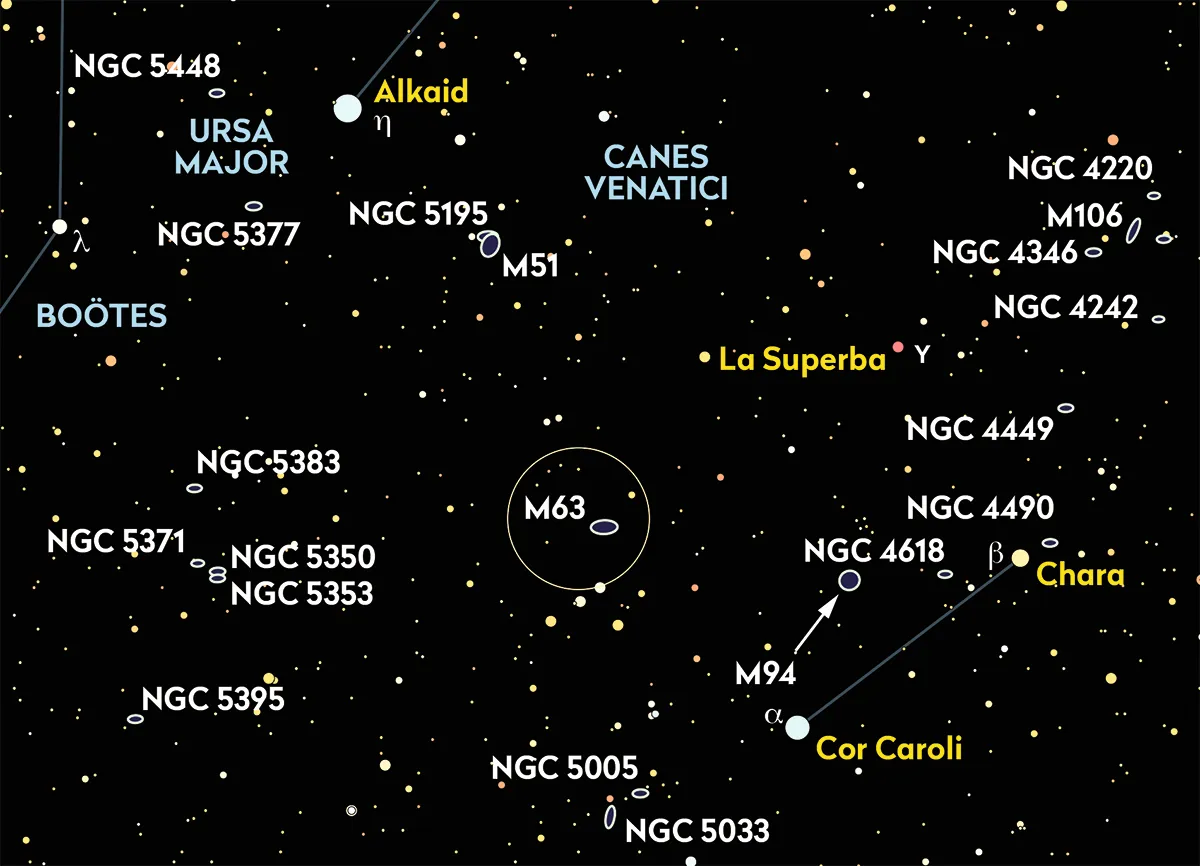

Sunflower Galaxy

Next, we’re going to move 5.7° south-southwest to M63, the Sunflower Galaxy.

Once the scope is trained on the proper field, you shouldn’t have to strain to see the Sunflower.

It’s small enough at 12.0 x 7.2 arcminutes that the light of this mag. 9.3 intermediate-inclination (half-way between edge-on and face-on to us) galaxy’s light is concentrated.

The question is, can you see the sunflower?

From dark sites, even with smaller instruments, M63’s dusty, patchy spiral arms make it look a little like a ghostly flower.

What can make it difficult to see M63’s arms?

Something I’ve often observed is that most amateur astronomers use too little magnification rather than too much.

Don’t be afraid to pump up the power to 150–200x.

Doing so spreads out the background light pollution in the field, increases contrast and maybe brings hints of the arms, even in compromised skies.

I have been able to see the arms of the Sunflower without much trouble in the suburbs, using a 10-inch instrument at higher powers.

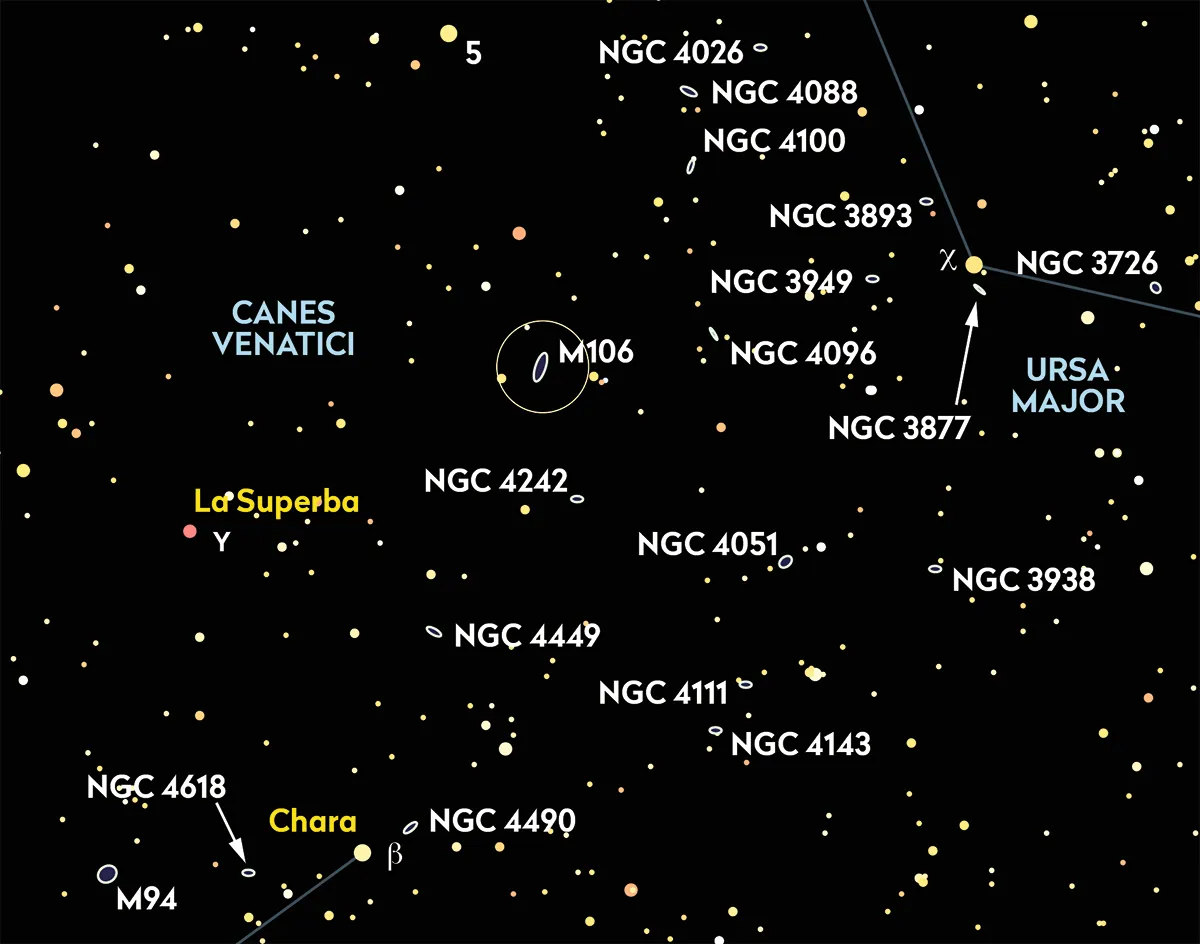

M106

From the Sunflower, still remaining in Canes Venatici, we make another leap in the dark, 11.4° northwest to M106.

It’s a galaxy that looks great in almost any scope in any skies.

At mag. 9.1, the light of this 16.6 x 6.3-arcminute galaxy is more spread out than M63, thanks to its closer-to-face-on orientation, but it is still bright as galaxies go.

Seeing it is not the problem. The challenge is seeing dark detail in its nebulous disc and the star lanes near its nucleus.

How do you get a better view of this one?

Human eyesight evolved to make moving objects easier to see than stationary ones: tap the tube of the scope until it jiggles a little and you may find more details popping into view.

This is one time when a rock-solid mounting isn’t a good thing.

We’ll take one last glimpse of this big galaxy and then leave M106 and Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs, behind.

Black Eye Galaxy

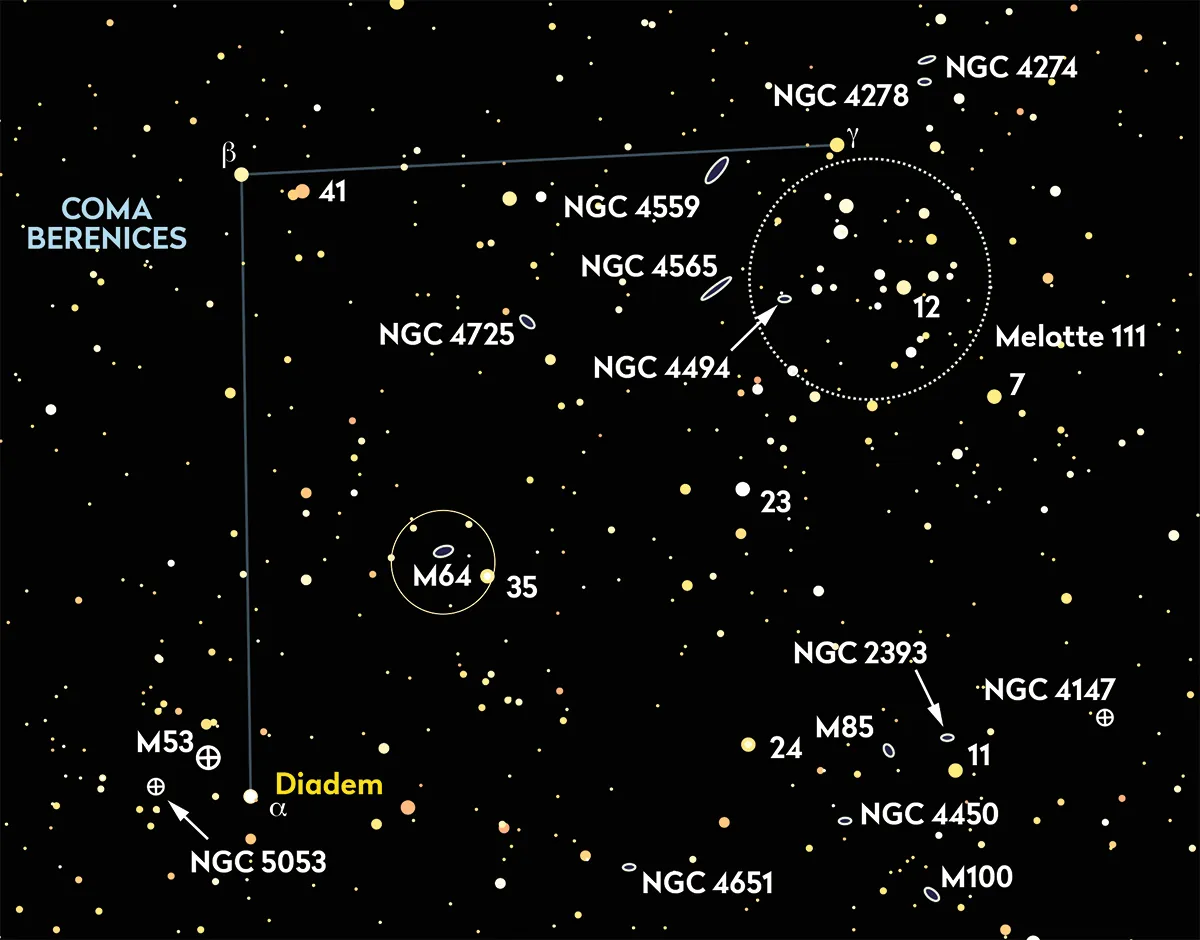

Next we'll move a full 26.8° southeast to the neighbouring constellation Coma Berenices and M64, the Black Eye Galaxy.

You’ll know you are in the proper spot when you see a dimly glowing (mag. 9.3), intermediate-inclination, 10.0 x 5.0-arcminute oval of light.

If that were all there were to see, it would be quickly checked off the observing list and we’d be on our way.

But it’s not; there’s something remarkable here.

This object is called the Black Eye because of an enormous spot of dark dust lying just outside its nucleus, a patch about 3 arcminutes across.

While not easy in heavy light pollution, the spot is detectable with an 8- to 10-inch telescope in suburban skies – if you know how to see it.

The ‘how’ is averted vision. The human eye has two types of sensors, the colour-sensitive cones

near the centre of the retina and the dim-light-sensitive rods at its periphery.

To see the faintest details, don’t look straight at M64, look off to its side.

With averted vision, the Black Eye and its spot may be easy as well as impressive.

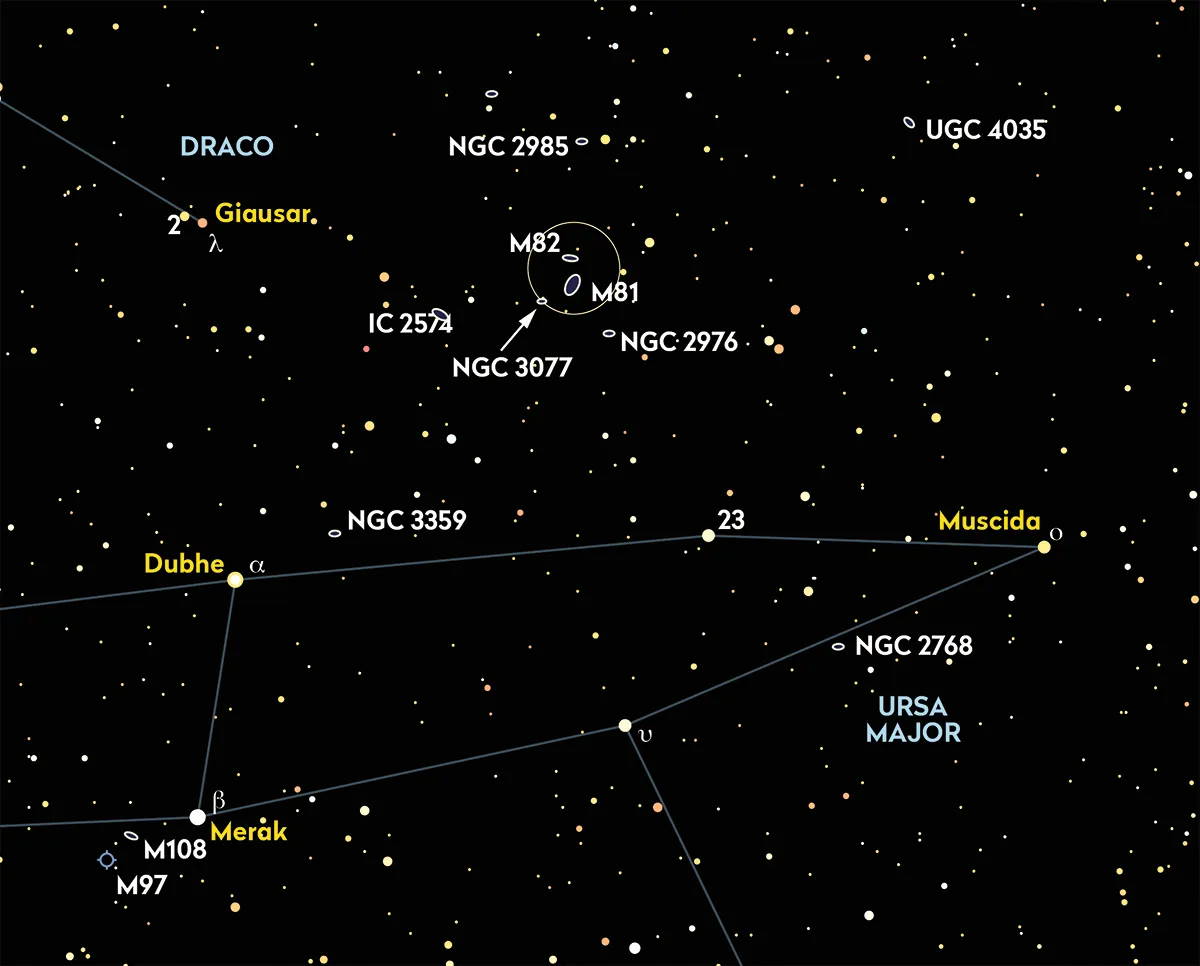

Bode's Galaxy and Cigar Galaxy

The hours are passing and the Bear is climbing higher.

And that is where we are going, to Ursa Major itself, for two of its most famous galaxies, M81, Bode’s Galaxy and M82, the Cigar Galaxy.

This is our longest star-hop of the evening, a full 55˚ to the north-northwest to the seldom visited northwestern area of the Bear.

Well, it would be seldom visited if not for the presence of two of the most spectacular galaxies in the northern sky.

M81 is our first stop. From a dark site, what is visible of this mag. 7.1 spiral is a bright core wrapped in a large 21.9 x 5.8-arcminute envelope of nebulosity.

This is often all that can be seen, even in large instruments.

From pristine sites, however, 12-inch and larger scopes reveal two delicate spiral arms.

Maybe you’ve heard the phrase ‘baby’s breath on a mirror’ used when describing faint nebulosity. It is certainly apt when talking about M81’s arms.

A mere 0.6˚ north of M81 is a galaxy that I consider even more spectacular: M82.

It’s a near-edge-on irregular galaxy that looks as if something bad has happened to it.

The 9.3 x 4.4-arcminute mag. 9.0 disc is crisscrossed by dark and bright lanes, giving it a disrupted appearance.

It is believed this was caused by a close encounter with M81 in the distant past.

When she was young, my daughter called M82 ‘the Exploding Cigar Galaxy’, and it certainly looks it.

Observing tips for the pair? Use a wide range of magnifications.

I enjoy using an ultra-widefield eyepiece that delivers enough power to show details in both, and a field wide enough to contain the two.

A favourite with my old 12-inch Dobsonian was a 12mm, 82˚ apparent field eyepiece. Seeing M81 and M82 in one field from a dark site was breathtaking.

Pinwheel Galaxy

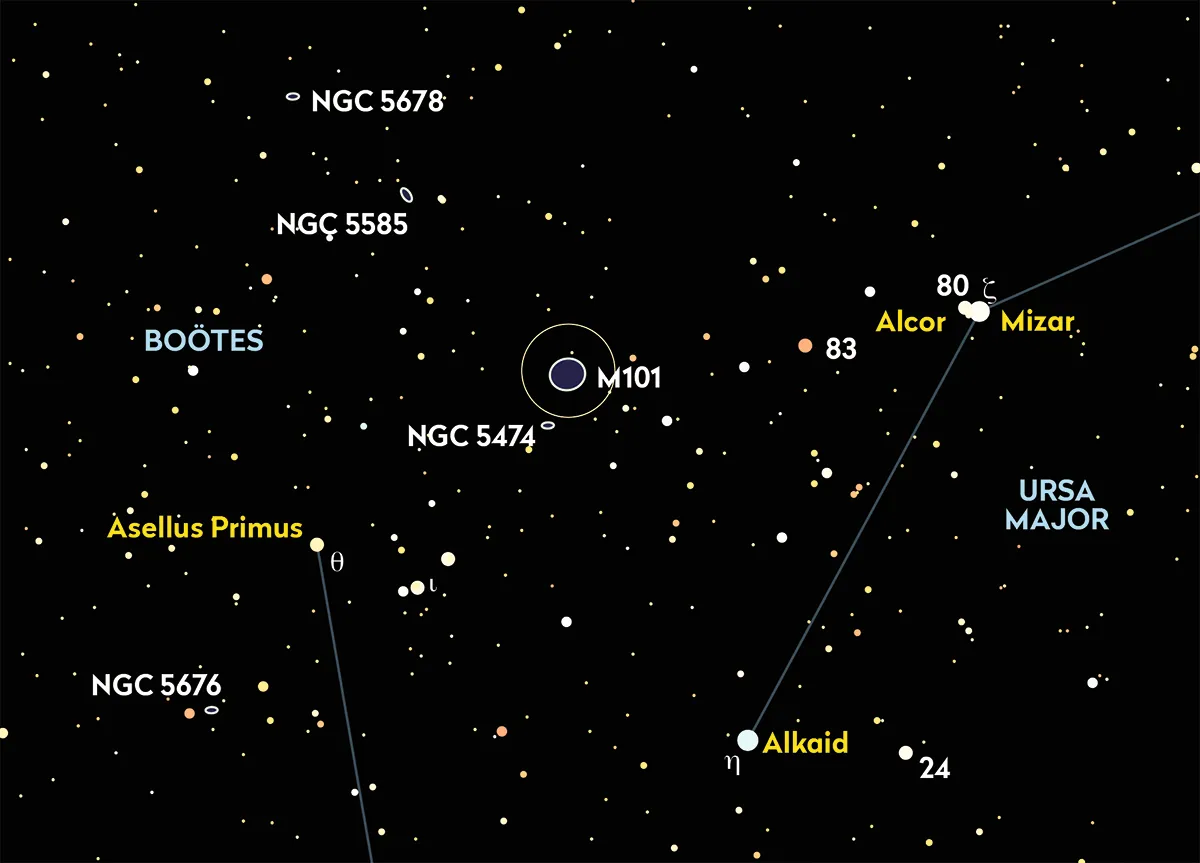

Let’s end the tour of Ursa Major galaxies on a distinct challenge: M101, the Pinwheel Galaxy.

There is no question that this enormous face-on spiral is one of the most beautiful northern galaxies.

Unfortunately, along with autumn’s Phantom Galaxy, M101 is also one of the most challenging.

But we’ve got our bag of deep-sky observing tricks; let’s try them on this marvel.

The Pinwheel is 35˚ east of M82, and is easy to find without a computerised mount since it forms an equilateral triangle with the Plough’s two bright stars, Alkaid and Alcor.

Or it would be easy if it weren’t so dim. As with all face-ons, it’s tough.

This 22.0 x 21.4-arcminute spiral galaxy nearly fills the field of a lower-power eyepiece and its bright integrated magnitude of 8.1 doesn’t mean it is easy for the visual observer.

I have seen the galaxy as a faint brightening in the field of an 8-inch telescope from badly light-polluted suburban skies.

From a dark site on an especially good evening, I’ve observed the spiral arms without difficulty with an 8-inch.

On a truly superior night in the mountains of West Virginia, I’ve glimpsed the Pinwheel’s arms with 10x50 binoculars.

M101 isn’t impossible, if you know how to observe it.

You should use all the tricks we’ve mentioned, but two others really help.

First is putting empty space around the galaxy. Use a widefield eyepiece to frame this big galaxy with dark sky and provide some contrast.

The other secret? For the Pinwheel, like other face-on galaxies, a good night means a dry as well as a dark one.

Any moisture in the air makes M101 difficult or even impossible to observe.

Final thoughts

It’s definitely not dry where I am this evening, as I write this.

Dew is falling and it’s chilly and damp, and thoughts turn to a warm den and something hot to drink.

Tonight, we only scratched the surface of the spring galaxies available to visual deep-sky observers

Leo and, most of all, Virgo with her great galaxy fields beckon.

But they will be there another night, and so will we, standing on the shore of a great, dark ocean, hunting bright treasures.

What are your favourite galaxies to observe, near Ursa Major or otherwise? Share your thoughts and images with us via contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com.