The James Webb Space Telescope has found strong evidence of a giant planet in the star system closest to our Sun.

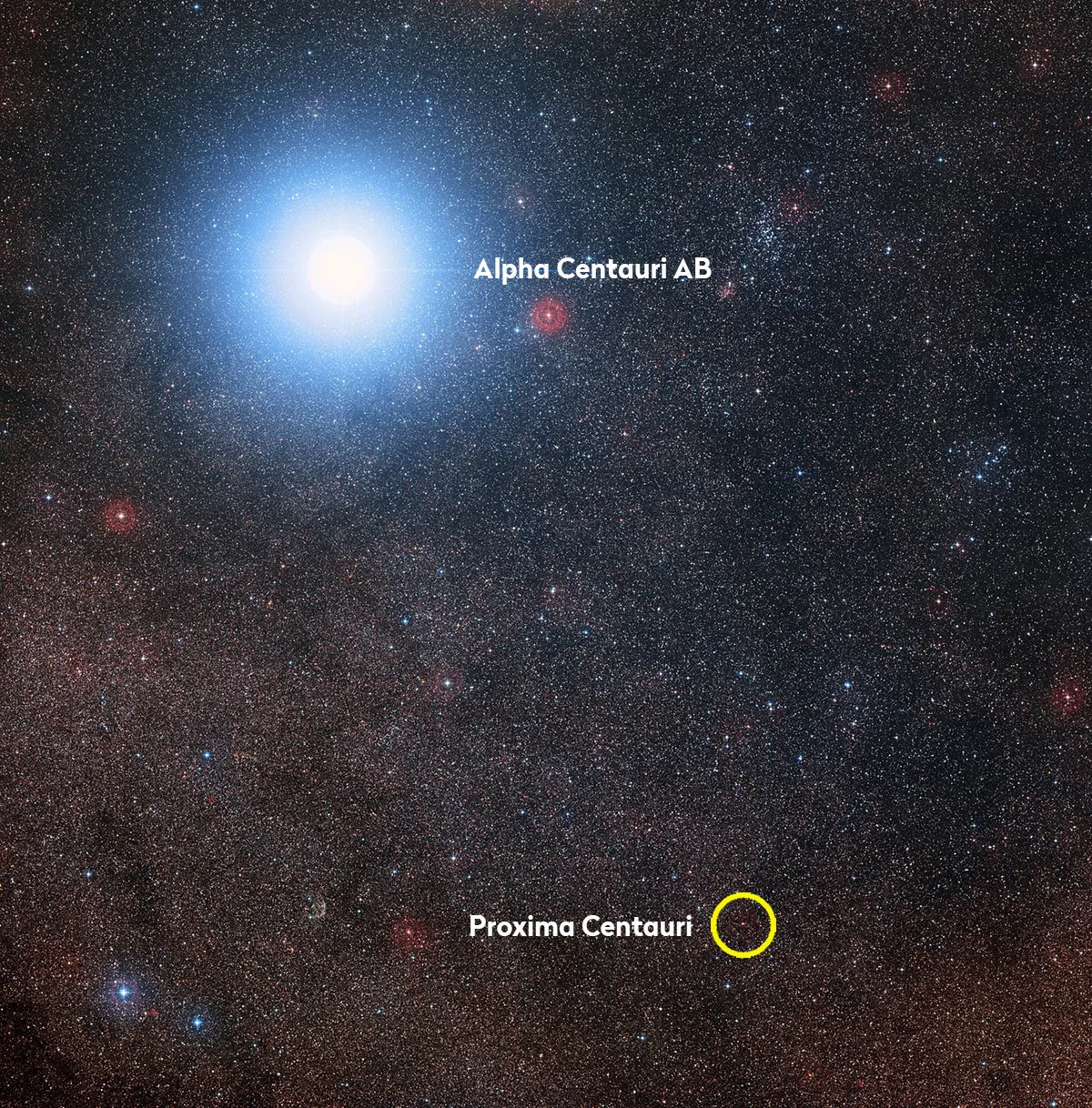

Alpha Centauri is a triple-star system just 4 lightyears from Earth, and a key point of interest for astronomers searching for planets beyond our Solar System.

More on exoplanets

If confirmed, the exoplanet would be the closest world to Earth ever found orbiting in the habitable zone of a Sun-like star.

Alpha Centauri, our closest stellar neighbour

The Alpha Centauri system is made of binary stars Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B, both of which are similar to our Sun, and faint red dwarf star Proxima Centauri.

Alpha Centauri A is the third brightest star in the night sky, but is visible only from the Southern Hemisphere.

Astronomers already know of three exoplanets around Proxima Centauri, but had never been able to locate worlds around Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B.

Webb may have just discovered one.

NASA, ESA, CSA, Aniket Sanghi (Caltech), Chas Beichman (NExScI, NASA/JPL-Caltech), Dimitri Mawet (Caltech)

Has Webb found a new world around Alpha Centauri?

The exoplanet candidate is a gas giant like planet Saturn in our own Solar System, meaning it could not support life as we know it.

But it does orbit in the habitable zone around its star, which means temperatures there are theoretically be cool enough for life to exist.

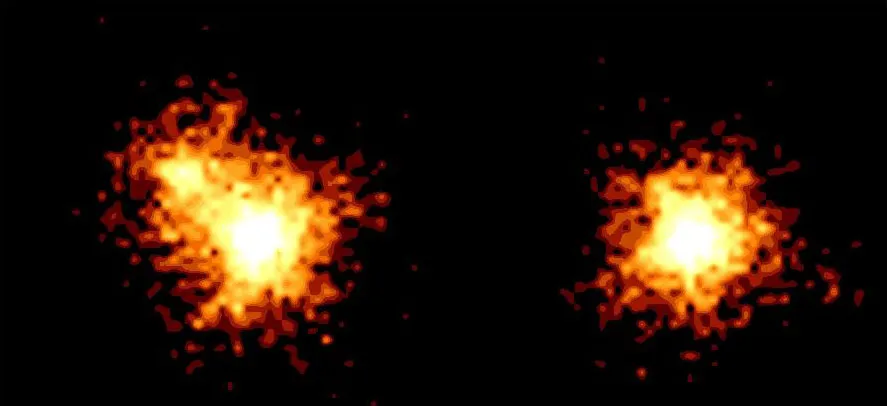

Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) enabled astronomers to catch a glimpse of the potential world.

"With this system being so close to us, any exoplanets found would offer our best opportunity to collect data on planetary systems other than our own," says Charles Beichman, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech’s IPAC astronomy center, co-first author on the new papers.

"Yet, these are incredibly challenging observations to make, even with the world’s most powerful space telescope, because these stars are so bright, close, and move across the sky quickly.

"Webb was designed and optimized to find the most distant galaxies in the Universe.

"The operations team at the Space Telescope Science Institute had to come up with a custom observing sequence just for this target, and their extra effort paid off spectacularly."

Unravelling the new world

Data from several observations by the Webb Telescope was studied by the team which, combined with computer modelling, suggests the source seen in the Webb image of Alpha Centauri is a planet, rather than a background object like a galaxy or a foreground object like a passing asteroid.

The first observations took place in August 2024, using an instrument called a coronagraph.

These block light from a star to enable astronomers to better see any faint planets in orbit around that star.

The team say extra brightness from nearby companion star Alpha Centauri B made spotting the potential planet tricky.

Bbut they were able to counteract light from both stars to reveal an object over 10,000 times fainter than Alpha Centauri A.

It orbits the star at a distance two times the distance between the Sun and Earth.

Frustratingly, additional observations of the system in February 2025 and April 2025 didn't reveal any objects like the one seen in August 2024.

In search of the lost planet

"We are faced with the case of a disappearing planet!" says PhD student Aniket Sanghi of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California, a co-first author on the two papers covering the team’s research.

"To investigate this mystery, we used computer models to simulate millions of potential orbits, incorporating the knowledge gained when we saw the planet, as well as when we did not."

The simulations took into account a 2019 sighting of a potential exoplanet candidate by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, as well as the new data from Webb.

They also considered what sort of planet orbits would be stable within the system, given the three-body-problem offered by the presence of Alpha Centauri B, which has the potential to fling any existing planet out of the system.

These simulations matched what the team had observed in the later observations.

"We found that in half of the possible orbits simulated, the planet moved too close to the star and wouldn’t have been visible to Webb in both February and April 2025," says Sanghi.

Based on Webb's mid-infrared observations of the potential planet, the team say it could be a gas giant, about the mass of Saturn, orbiting Alpha Centauri A.

Its elliptical path could place it between 1 to 2 times the distance between Sun and Earth.

"These are some of the most demanding observations we've done so far with MIRI's coronagraph,” says Pierre-Olivier Lagage, of CEA, France, a co-author on the papers.

"When we were developing the instrument we were eager to see what we might find around Alpha Centauri, and I'm looking forward to what it will reveal to us next."

"If confirmed, the potential planet seen in the Webb image of Alpha Centauri A would mark a new milestone for exoplanet imaging efforts," says Sanghi.

"Of all the directly imaged planets, this would be the closest to its star seen so far.

"It's also the most similar in temperature and age to the giant planets in our Solar System, and nearest to our home, Earth.

"Its very existence in a system of two closely separated stars would challenge our understanding of how planets form, survive, and evolve in chaotic environments."