Mariner 9 was launched on 30 May 1971 on an Atlas-Centaur rocket. It reached Mars less than six months later and went into orbit, ready to begin analysing the atmosphere and mapping the surface.

All went well but NASA’s planners had no control over one factor – Martian dust storms. These are common enough, carried by the winds on Mars, and can become global.

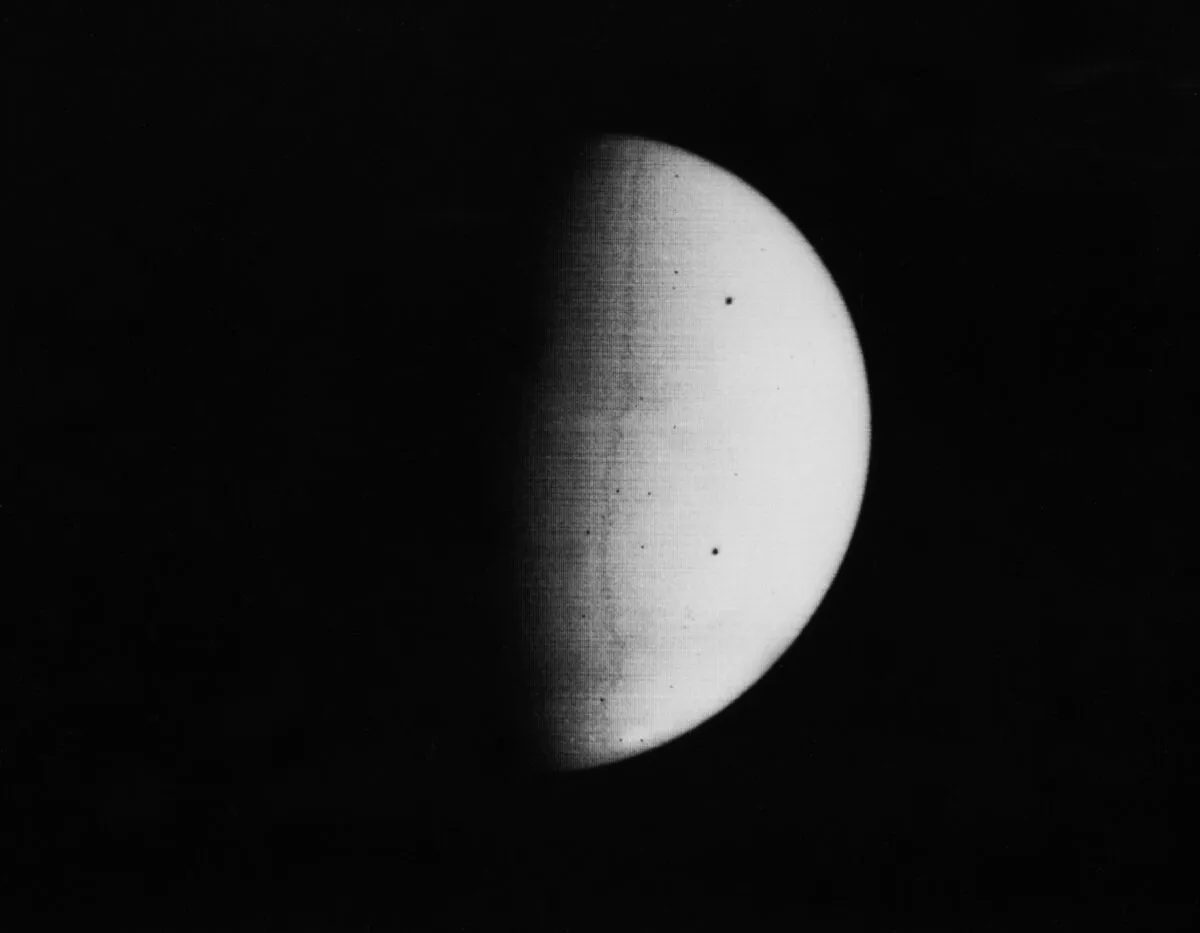

When Mariner 9 arrived, one of these storms was in progress and the surface features were hidden.

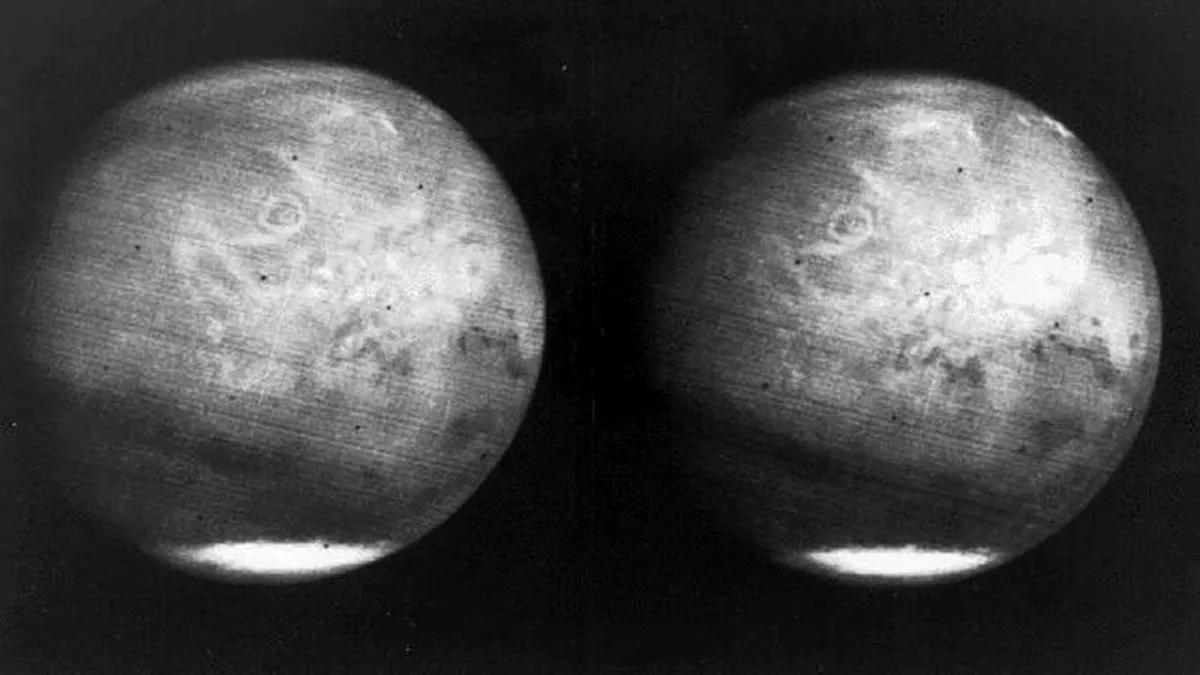

Gradually the dust settled and gave us views of Mars showing that by sheer bad luck, Mariners 6 and 7 had imaged the planet’s least spectacular part.

These were among the first spacecraft to reach Mars and Mariner 9 had plenty to do, particularly because of the failure of its twin, Mariner 8.

For more on Mars, read our guide What does the night sky look like on Mars ? or find out how humans will survive the journey to Mars.

Mariner 9 mission timeline

- 30 May 1971 Mariner 9 launches

- Nov. 14, 1971 Mariner 9 enters orbit around Mars

- Jan. 2, 1972 The first images by Mariner 9 are beamed back to Earth

- Feb. 11, 1972 NASA reveals Mariner 9 has met its objectives

- Oct. 27, 1972 Mission scientists make their last contact with the spacecraft

Revealing the secrets of Mars

Although I cannot remember the time when Mars was believed to be inhabited, my memory does go back to when our ideas about it were very different. Planetary scientists and astronomers used to have very strange ideas about Mars.

The dark areas were vegetation tracts; the white polar caps were due to a thin layer of solid carbon dioxide; the surface was fairly uniform, with no high mountains or valleys; the atmosphere was made up chiefly of nitrogen; the red regions were deserts, covered with sand of the type you find at Bognor Regis.

In fact, all these assumptions were wrong.

The great breakthrough in our understanding of Mars was due to two spacecraft, Mariner 4 and above all Mariner 9.

The Mariner 4 mission of 1964 had sent back 21 images and these were good enough to show that the surface was more interesting than had been expected.

There were mountains and valleys, though canals were conspicuous only by their absence.

The dark regions were not due to vegetation: they were regions where the reddish material had been blown away by winds exposing the darkness beneath.

Mariner 6 sent back 75 photographs while Mariner 7 managed to produce 126 images, mainly of the southern hemisphere, before contact was lost.

All of the other pre-1971 probes originated from the USSR - this was the height of the Space Race after all - but little data was received, and the only thing landed on Mars was a Soviet pennant.

It is strange that even now the Russians have had no luck with Mars, particularly as they have been so successful in their exploration of Venus, which should have been a more difficult target.

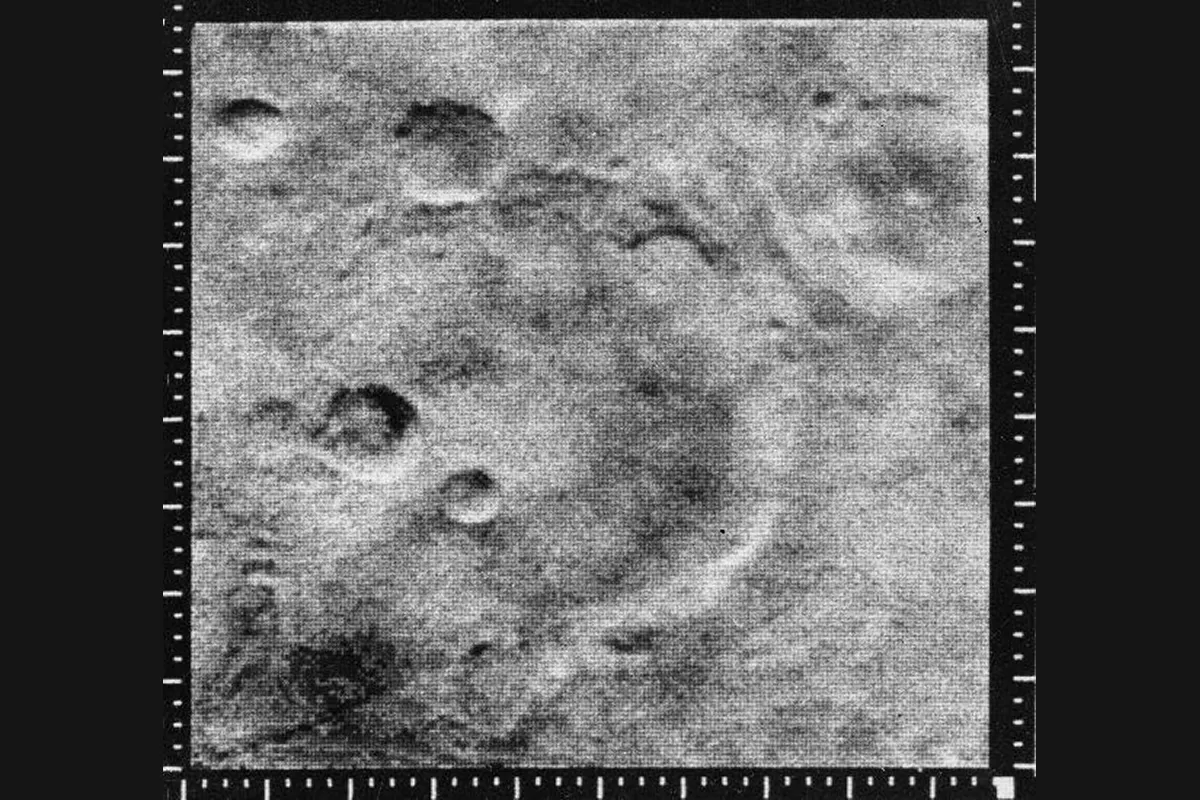

The images Mariner 9 sent back showed details of all kinds. There was a vast system of canyons, over 4,000km long, now known as the Valles Marineris.

But perhaps the most striking of all were the volcanoes, some of them dwarfing any volcanoes of Earth.

Loftiest of all is Olympus Mons, towering 25km above the land below and topped by an enormous, complex caldera.

Another feature of special interest is Hellas, south of the Syrtis Major. It is circular and becomes so bright that it looks like an extra polar cap.

It had been regarded as a snow-covered plateau – in fact it is a deep basin that can be filled with white clouds.

Mariner 9 sent back its last signals on 27 October 1972 and continued in its orbit, silent and undetectable.

It will not be a permanent member of the Solar System as around 2022 it will enter the Martian atmosphere.

It has done its work better than its makers had dared to expect and it has an honoured place in scientific history.

This article was originally published in BBC Sky at Night Magazine in May 2011.