Over the course of the Star Wars saga audiences have been taken on a journey not only aboard spaceships and battle stations, but across a host of mesmerising planets.

As we look deeper into our own Galaxy we are finding more and more strange new alien worlds.

Even in our own Solar System there are exoplanets and exomoons very familiar to those seen in the Star Wars universe.

So what can real exoplanet science tell us about the likelihood that planets like those we see in the Star Wars galaxy could actually exist?

For more exoplanet oddities, read our guide to the weirdest exoplanets.

Star Wars fan? Read our pick of the best space and sci-fi films of all time.

7 Star Wars worlds we know could actually exist

The asteroid field

To evade being shot down by Tie Fighters in The Empire Strikes Back, the Millennium Falcon hides out in an asteroid field.

The asteroid field of the film is a densely packed place, filled with rocks that are constantly colliding and hitting the ship. But in reality, you’d have to be trying quite hard to even find an asteroid, let alone be struck by one.

If you landed the Millennium Falcon on a body in our Asteroid Belt the nearest one would be nearly 1 million km away: you’d need binoculars to see any evidence of it.

The region hasn’t always been this sparse though. It’s estimated that the Asteroid Belt contained as much as 1,000 times more mass than it does now, but shortly after its formation collisions and gravitational disturbances would have thrown out most of the debris.

Even if the belt still had its initial mass, it would be hundreds of thousands of kilometres between asteroids.

In other planetary systems more compact asteroid belts have been found, most within the snow line, the radius at which ice forms in a planetary disc.

Beyond this giant planets tend to disperse the asteroids. Some asteroid belts have been found with as much as 25 times more mass than the one between Mars and Jupiter.

This would still leave huge gaps between the space rocks, not the densely packed field depicted in the film. If a belt were that dense, the constant collisions between the rocks would soon grind them down into little more than dust.

Tatooine

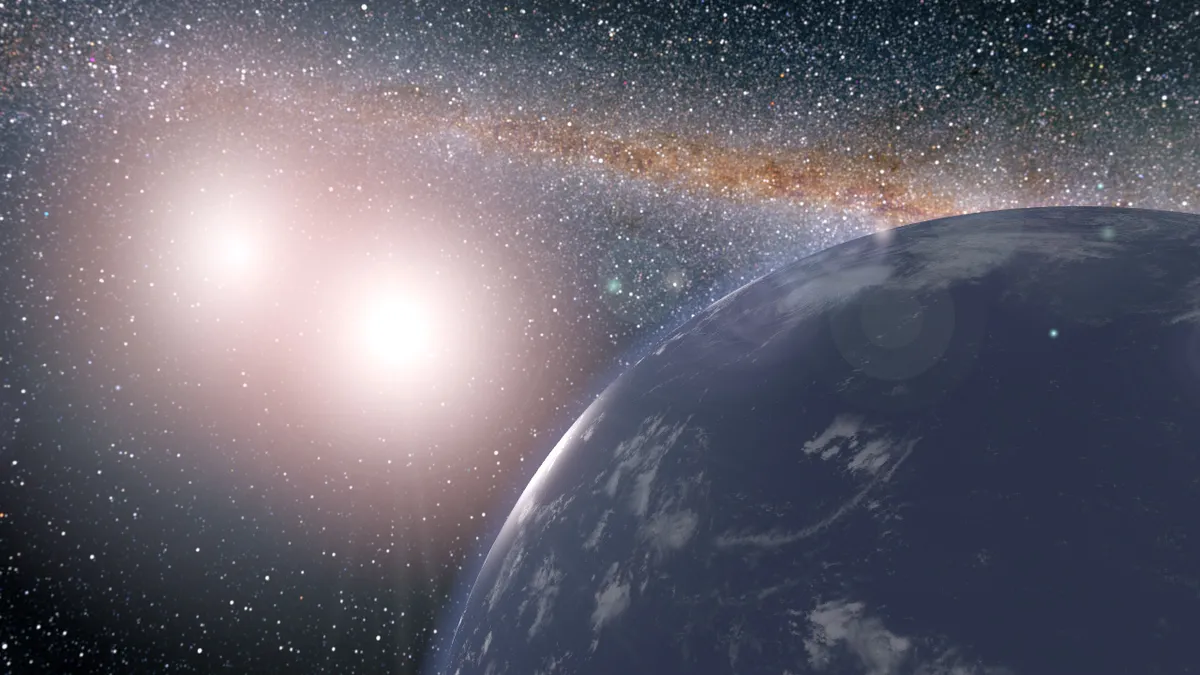

In A New Hope, Luke Skywalker looks to the horizon on his home planet of Tatooine at the twin suns setting in the distance. The desert world orbits not one, but two stars, locked in a binary pair.

In our own Galaxy several ‘Tatooine’ worlds have been found in the form of exoplanets orbiting two, three or even four stars, though so far all of these have been gas giants. No rocky worlds have been spotted yet.

“A close pair of stars acts much like a single star except that the planet will move back and forth a little as the stars swirl around each other,” says Ben Bromley, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Utah.

“While this additional jostling is not a huge effect, it is enough to cause the building blocks of planets to crash into each other, leading to the destruction, not the growth of a planet.”

However when Bromley simulated the growth of planets in a debris disc surrounding a double star (like Zeta Reticuli in the southern hemisphere sky) he found that they could form even under these unstable conditions.

“Despite the jostling, the building blocks can settle on orbits that ebb and flow with the stars’ motion, and then they don’t destroy themselves when they collide. In this way planets can grow.”

Bespin

Cloud City, home of Lando Calrissian, floats in the atmosphere of a gas giant called Bespin in a layer that conveniently has the right pressure and oxygen level to support life.

In reality gas giants are not so helpful when it comes to supporting cities. While there are layers that are around the atmospheric pressure of Earth, the atmosphere of gas giants is almost exclusively hydrogen and helium.

Will we ever find life beyond Earth? So far no gas giant has been found with the level of oxygen needed to sustain human life.

But the idea of a floating city hovering above a planet, in the atmosphere, is not that far fetched. Zeppelin-inspired spacecraft have long been suggested as a way of exploring Venus, which has a thick atmosphere of carbon dioxide.

As breathable air is predominantly made of the lighter gasses nitrogen and oxygen, an enclosed station would float just like a helium balloon in Earth’s atmosphere.

Hoth

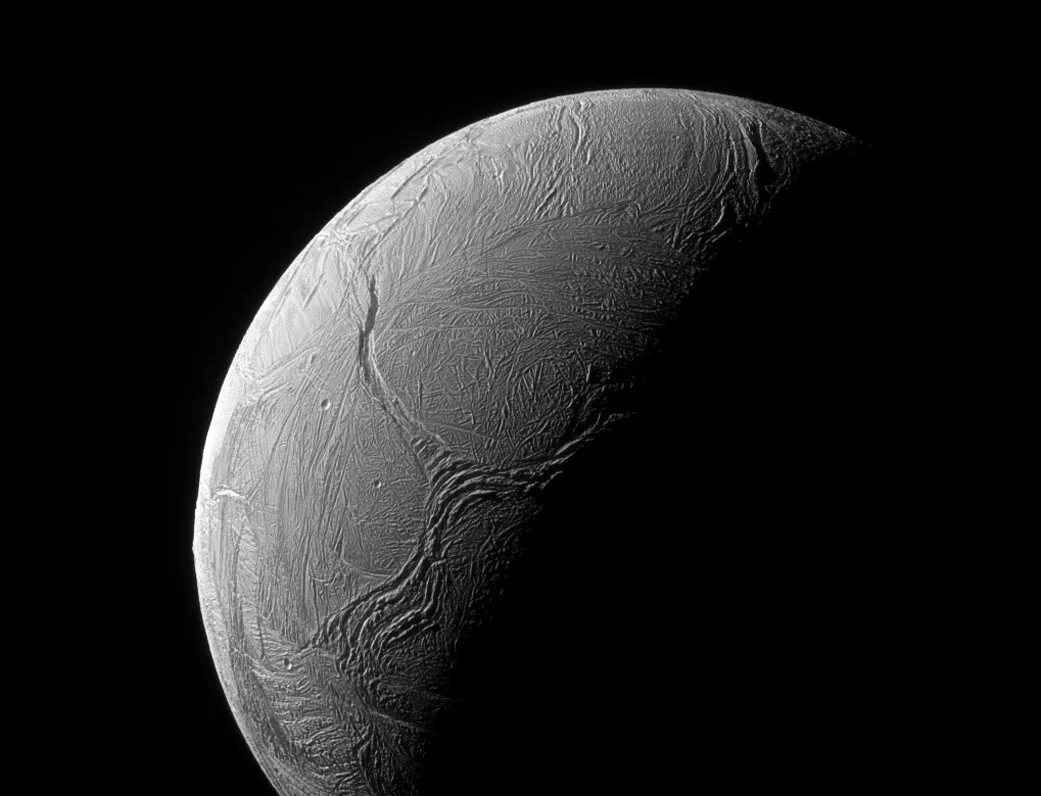

An inhospitable world like the ice planet Hoth is the perfect place to hide a rebel base, as seen in the opening scenes of The Empire Strikes Back.

Within our own Solar System there are many moons, such as Europa and Enceladus, that are completely encased in ice, but with no atmosphere and temperatures around -170ºC it’s unlikely anyone would be able to survive on these worlds, even with a Tauntaun to cut open and spend the night inside.

However, a long time ago there was a planet in our Solar System that bore a striking resemblance to Hoth – our own Earth when it passed through the last ice age.

As the temperature dropped, the world froze over and the bright white snow and ice that formed reflected more sunlight back into space, causing it to get even colder.

Luckily for us a few volcanoes managed to poke through the ice, spewing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. With no liquid water to soak it up, the gas formed an insulating layer, which trapped heat and melted the ice within a few thousand years.

If there is a Hoth out there in the Universe, the chances are it won’t remain inhospitable for long.

Kamino

In Attack of the Clones, an army is secretly built and raised on the water-covered planet of Kamino.

When considering the reality of a global ocean worlds there is one big issue – when we can’t explain where the water on Earth came from, how could a planet form with enough to cover the entire surface?

"Earth actually has a lot more water than you can see," says Laura Schaefer from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

"We think the mantle of the Earth has at least the same amount as is on the surface, maybe even five to 10 times more. One way to get a totally ocean-covered planet is just to heat up the interior and drive all the water to the surface through volcanoes.

"Another is to form the planet further away from the central star, where the protoplanetary disc was colder and water could condense, so the planet just forms with more water in the first place."

There have been suggestions that several exoplanets may be ocean worlds. GJ 1214b has 6.5 times the mass Earth, but a density more like water than rock, suggesting that it is 50% water. Yet finding direct evidence of an ocean planet could be difficult.

“Water vapour tends to condense out into clouds on temperate planets and clouds will block our view of the surface, where most of the water would be,” says Schaefer. “Another way is to look for the glint of sunlight on the water, but on a global scale.”

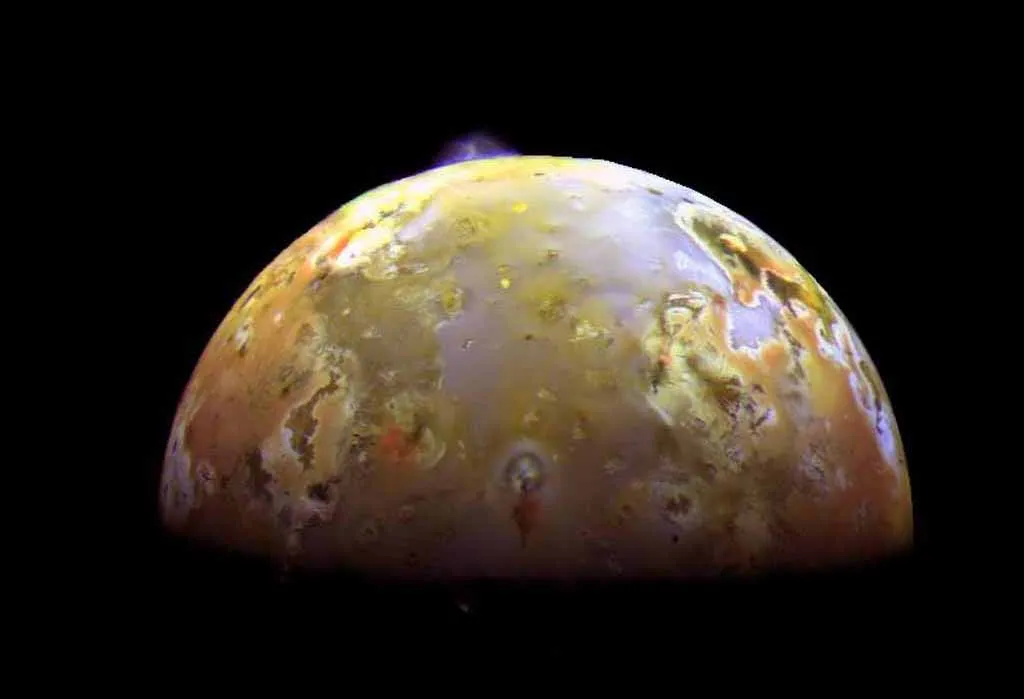

Mustafar

During the climax of Return of the Sith, Anakin Skywalker and his mentor Obi-Wan Kenobi have a grand face-off on the planet of Mustafar, fighting to the finish on a river of lava.

In its early days, our Solar System was filled with rocky bodies being torn apart by intense volcanism, but these quickly cooled over the first few hundred million years.

Not all worlds stayed sedate for long, however. When the orbits of two or more moons sync up in a resonance, the resulting gravitational tug of war pulls the internal rock or ice of a planet.

The friction this creates causes a huge amount of heat to be generated. On ice moons such as Europa and Enceladus this process forms liquid oceans beneath the icy crust, but the effect is most impressive on Jupiter’s rocky moon Io.

Despite only being about the size of Earth’s Moon, Io is the most volcanically active world in the Solar System.

It is covered in volcanoes and has lava flows as long as 300km. Depressions in the surface can even become filled with molten rock, creating lakes of lava that are then covered by a thin crust.

However, Io’s atmosphere is 90% sulphur, and the air of any volcanic world would most likely be highly toxic, making lightsaber battles of good verses evil much more difficult.

Coruscant

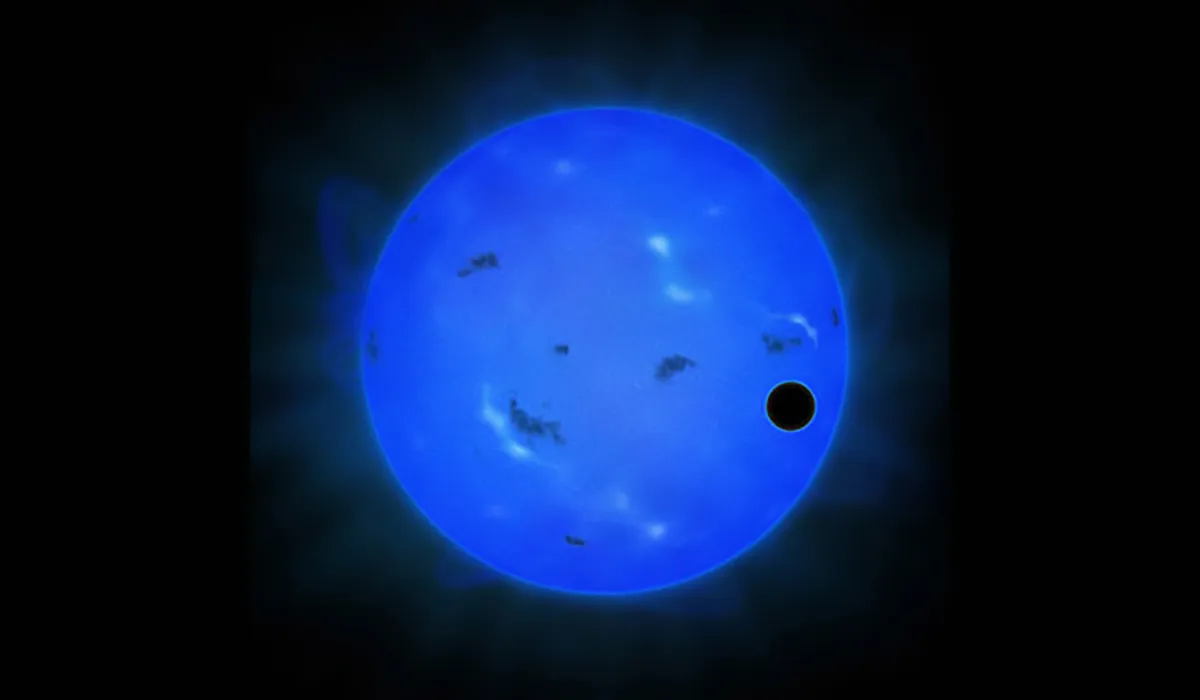

At the centre of the Star Wars galaxy lies Coruscant, a planet covered in one huge metropolis and home of the Galactic Senate.

If some civilisation within our own Galaxy had fully industrialised a planet, it could give humanity its best chance yet of finding intelligent life.

Currently exoplanet research is concentrated on finding life from markers such as methane or oxygen in a planet’s atmosphere, known as biosignatures.

These could indicate the presence of basic life, but advanced civilisations would leave signs that could also be detected.

“We could detect industrial civilisations through their pollution of the planet’s atmosphere with artificial chemicals that do not form spontaneously in nature,” says Avi Loeb, chair of the Astronomy department of Harvard University.

“To be detectable, industrial pollution by CFC molecules needs to be at least 10 times larger than currently found on Earth.”

Urbanisation on the scale of Coruscant would have dramatically changed the planet’s atmosphere. It’s likely that any civilisation would take similar steps, as humans have done, to reduce emissions of most harmful atmospheric pollutants.

However one area of pollution that has generally gone unchecked, as any city astronomer can attest, is light pollution.

Though it would be difficult to pick out the signal against the background starlight, the light from our street lamps could be travelling much further than we think.

“It turns out that existing telescopes could detect the light from a city like Tokyo all the way to the edge of the Solar System,” says Loeb.

This article originally appeared in the December 2015 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.