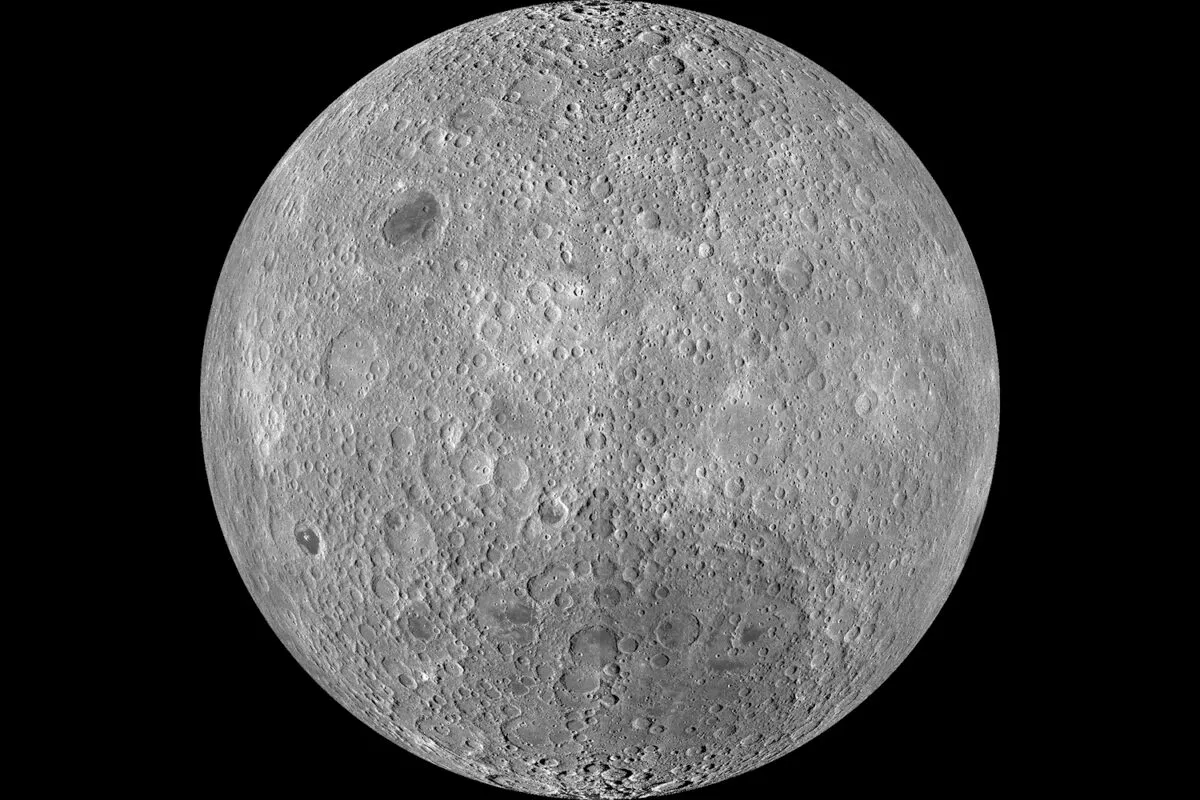

From our perspective on Earth, we always see the same side of the Moon, and we know this because if we look at the Moon on a regular basis, its phases may change but we always see the same craters and other features.

The distinctive pattern of bright highlands and dark lunar maria on the Moon has been turned towards us for millennia, visible to every human who has ever stood on Earth.

But why do we only see this one side of the Moon? We know that Earth spins about its axis, so why don’t we get to see the full lunar surface as our Moon does the same?

The Moon spins, so why don't we see different sides of it?

In simple terms, the Moon rotates once every 27.3 days, which is the same amount of time it takes for the Moon to orbit our planet. The result? On Earth we always see the same side of the Moon

Although this is not strictly true, either. We do get to see slightly more of the Moon than half of the Moon's surface at due to a wobbling effect known as lunar libration.

If the Moon were to spin faster or slower than once per orbit we would see all of it.

In the proper astronomical parlance, we say that the Moon is ‘tidally locked’ to Earth

You may also come across the expression ‘synchronous rotation’, which means the same thing.

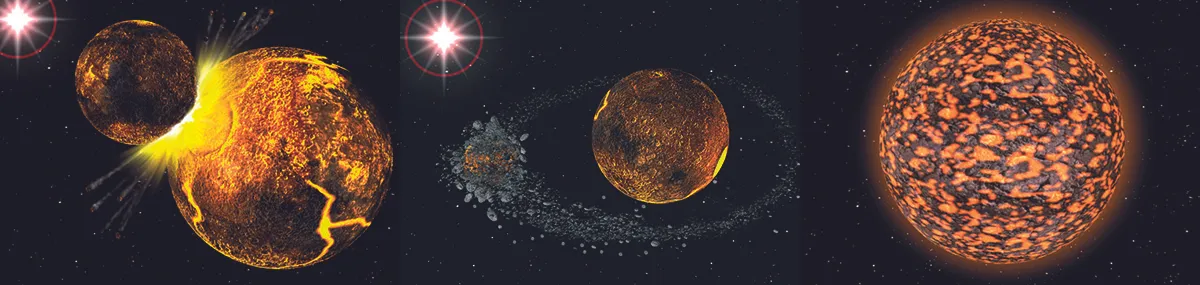

How the Moon became tidally locked

When the Moon formed some 4.5 billion years ago, it was spinning much more rapidly than it is today.

Earth’s gravity causes a rocky tidal bulge in our companion, which means it is lemon-shaped rather than a neat sphere, with a pinched end facing our planet.

Back in the Moon’s fast-spinning early history, the location of that bulge kept changing, shifting across the surface much in the same manner as our ocean tides.

This effectively acted as a brake, gradually slowing our companion’s spin speed until it fell into equilibrium with its orbital period.

At this point the hemisphere facing us became locked in place.

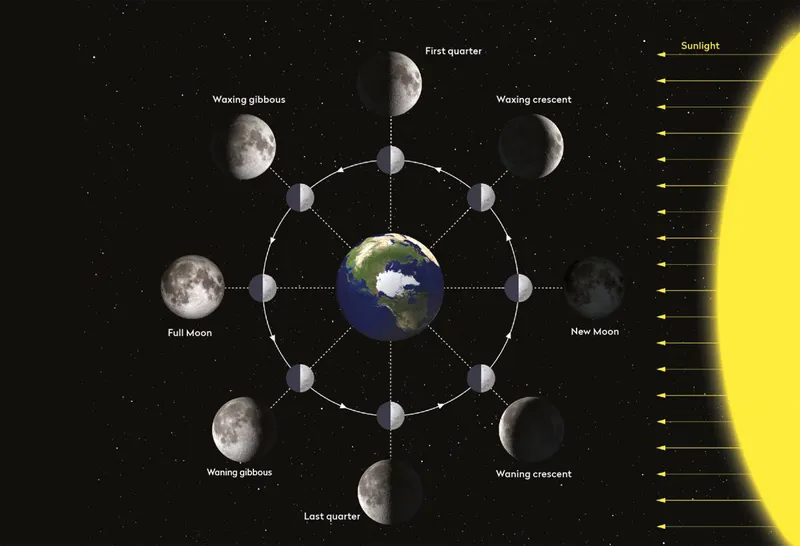

Why the Moon's appearance changes

Though the Moon always keeps that same side towards us, even a cursory glance will show you that it is not consistently illuminated from one night to the next.

What you are seeing here is the changing phase of the Moon. By phase, we simply mean the proportion of sunlit Moon visible from Earth.

The essential point to remember is that although only a fraction of the Moon may be lit from our vantage point, a full 50% of the Moon is lit at any one time. We just can’t always see it.

This is why astronomers don't like to refer to the side of the Moon facing away from us as the 'dark side', because this is not always true. Instead, we refer to the far side of the Moon.

The cycle of lunar phases (also known as a lunation) runs from new Moon to full Moon and back again, passing through crescent Moon, quarter Moon and gibbous Moon along the way, and takes 29.5 days to complete.

For more on this, read our guide to the phases of the Moon and find out when the next full Moon is appearing.

The lunar cycle/orbit discrepancy

Although it takes the Moon 29.5 days to complete a lunar cycle (a period known as the synodic month), it only takes 27.3 days to complete one orbit of our planet (a sidereal month).

This discrepancy arises from one lunar cycle being defined as the time it takes for the Moon to return to the same phase as seen by an observer on Earth.

Because Earth itself is moving, hurtling through space on its own orbit around the Sun, it takes the Moon that little bit longer to catch up than complete an orbit of its own.

You may also wonder why, given the Moon sits in the middle of a line with Earth and the Sun at the point of new Moon, a solar eclipse is such a rare event.

And likewise, why we don’t experience guaranteed lunar eclipses at the time of full Moon. It’s because the Moon’s orbit around Earth is tilted by around 5° with respect to Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

What happens, in most instances, is a near miss.