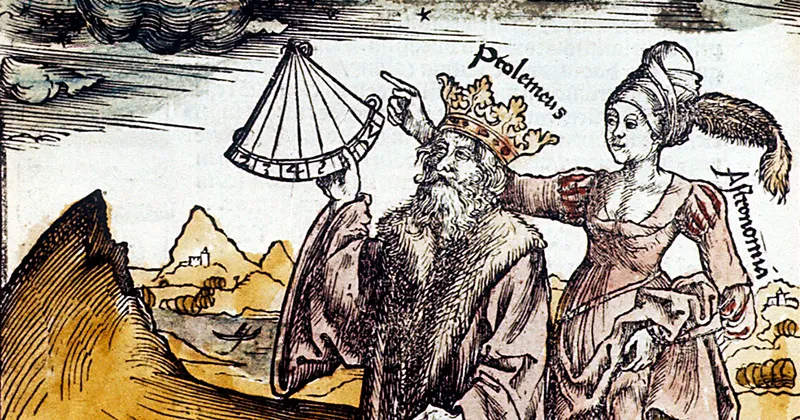

Claudius Ptolemaeus (circa AD 100–170), better known as Ptolemy, was a Greco-Roman astronomer, mathematician, geographer and cartographer.

He was a citizen of Alexandria, Egypt, in the 2nd century AD.

Although his writings influenced astronomy for over a millennium – not always correctly – very little is known about his life.

Ptolemy's Almagest and geocentrism

Ptolemy devoted most of his time and effort to astronomy.

His first major work was the 13-volume Almagest, meaning ‘the greatest’ and known to him as the Mathematike Syntaxis (The Mathematical Collection).

It was a synthesis of all the results obtained by Greek astronomy up to then, especially the earlier findings of Hipparchus, providing a model for astronomical functions and movements of heavenly bodies.

In the Almagest, he introduced the geocentric system, arguing that Earth was stationary at the centre of a large crystalline celestial sphere – the Universe – around which the stars and planets orbited in a broadening nested circle of spheres.

However, as we now know today, all the planets – including Earth – orbit the Sun.

This means our celestial neighbours appear to move back and forth across the night sky.

To explain these strange motions, Ptolemy employed an ingenious system of epicycles, originally devised by Apollonius of Perga (circa 240–190 BC).

This asserted that there was a large circle centred on Earth, known as the deferent.

Each heavenly body moved along its own smaller epicycle, which moved around the circumference of the deferent.

This became known as the Ptolemaic system – attributable not so much to the Almagest but to a later two-book treatise Hypotheseis tōn planōmenōn (Planetary Hypotheses).

Other volumes in the Almagest described the daily rise and setting of heavenly bodies, the motion of the Sun through the zodiac and the motion of the Moon.

Capitalising on Hipparchus’s earlier work, Ptolemy calculated the sizes and distances of the Sun and Moon.

He was able to determine that the Sun was considerably larger than Earth, though he still deemed our planet to be the centre of the Universe.

The stars and planets

Later volumes were dedicated to solar eclipses and lunar eclipses, the motion of the stars and the precession of the equinoxes.

Also included was his famous star catalogue.

The list was based on one created by Hipparchus centuries earlier, but increased the number of stars from 850 to 1,022. They were separated into 48 different constellations that form the basis of those we recognise today.

In the remaining volumes of the Almagest, Ptolemy modelled the motions of the planets more precisely.

The final volume he dedicated to what he called motion in latitude, tracking the apparent path of the Sun against the stars.

In conclusion, Ptolemy proposed that the planets were closer to Earth than the fixed stars, but their sphere was not the outer limits of the Universe; there were other spheres and the Universe was eternal.

The geocentric model spread throughout the classical world, eventually making it to the hands of Arabic astronomers who gave it the name Almagest.

It formed the basis of our knowledge of the Universe for centuries, until Copernicus put forward the heliocentric model in the 16th century.

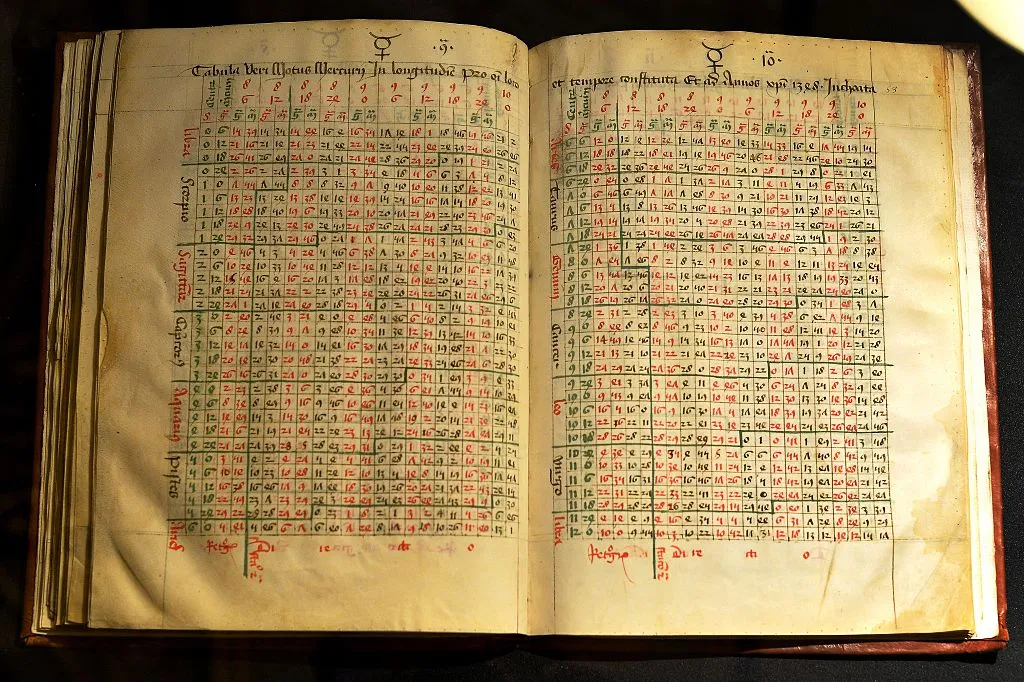

Despite its mistaken model of the Universe, the Almagest still contained a collection of astronomical tables that allowed astronomers to calculate the motions of the heavens.

Ptolemy later rearranged these into a set of ‘Handy Tables’ for more convenient, practical use.

Ptolemy's legacy

He later wrote the four-volume Tetrabiblos, the Almagest’s astrological counterpart.

The work once again gathered material from earlier sources, providing a comprehensive thesis on how the heavens were thought to affect Earthly matters, and was regarded at the time as being as authoritative as the Bible.

He also wrote on other areas of science, including a major work on geography, a thorough discussion on maps and the geographical knowledge of the Greco-Roman world, as well as lesser works on harmonics (musical theory) and optics.

Ptolemy was clearly indefatigable and his astronomical theories, whether right or wrong, stood for over a thousand years.

This guide appeared in the February 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine