Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the Soviet Luna programme explored the Moon not just from orbit, but from the surface, as it vied with the US in the Space Race.

As multiple space agencies set their eyes firmly on returning both uncrewed and crewed missions to the Moon over the coming years, here we'll take a look back at the history of the Soviet Luna programme.

The first missions of the Soviet Luna programme

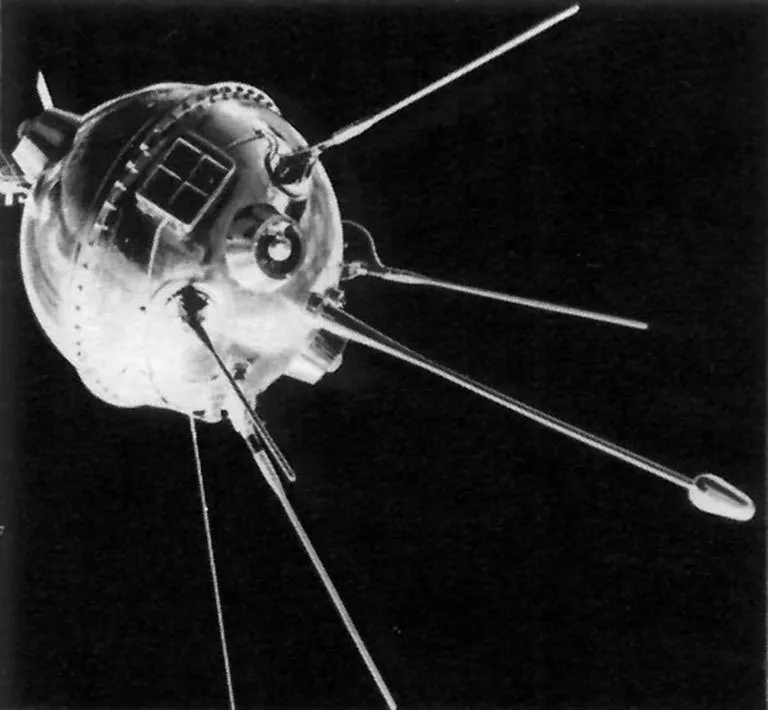

In 1957, the first two Sputnik missions successfully launched the first craft and first living creature into space, an apparent demonstration of the nation’s technological prowess over the US.

You can find out more about this in our history of animals in space.

To cement this view on the global stage, Soviet leaders wanted another first, and so they turned their attention to the Moon.

On 4 January 1959 the nation’s third ever spacecraft, Luna 1, sailed just 6,000km past the Moon, becoming the first human-made object to leave the Earth-Moon system.

- The story of Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space

- The life of Russian rocket pioneer Sergei Korolev

Several years later it would come to light Luna 1 was actually meant to impact the surface but had missed.

Following the Soviet tradition of obscuration, they’d claimed that was what they’d meant to do all along.

Given the secrecy surrounding the mission and its intentions, it’s perhaps unsurprising that many in the West didn’t believe Soviet claims of having launched any spacecraft at all, proclaiming it was a “Great Red Lie”.

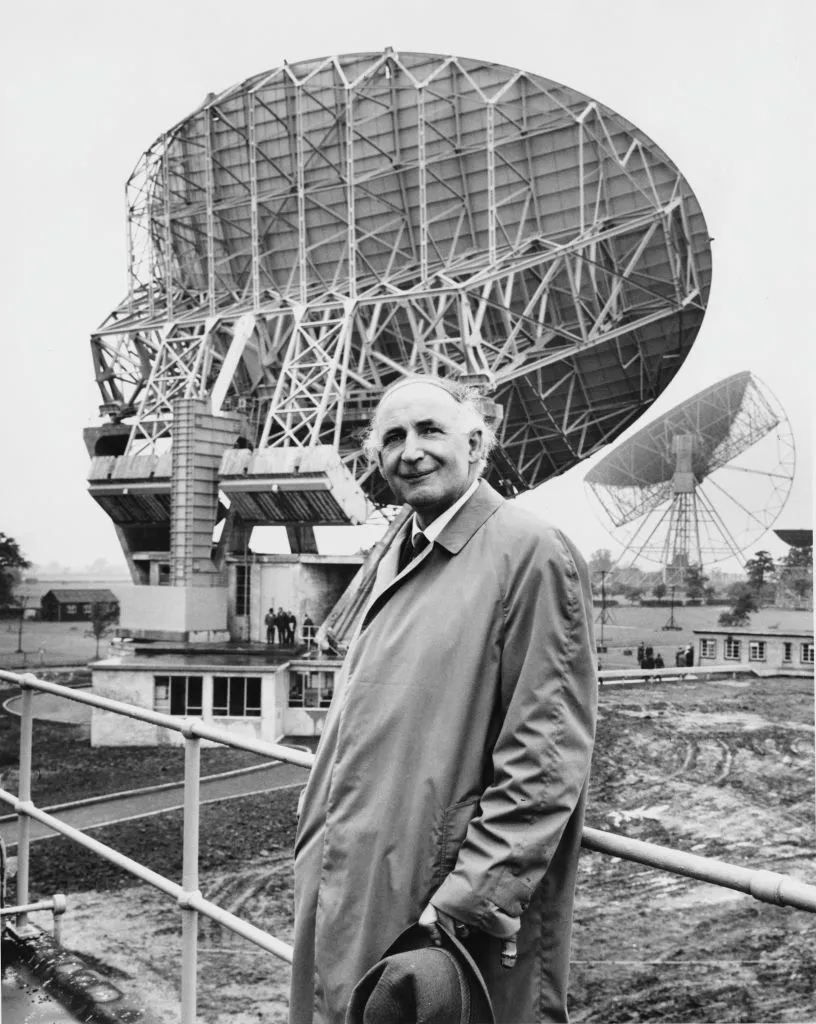

To ensure their achievement was beyond doubt and prove their lead in the Space Race, the Soviets made sure to notify Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, UK of Luna 2’s launch ahead of time, so the facility could track the spacecraft with their radio telescope.

On 13 September 1957, Jodrell Bank heard the steady beeping of Luna 2’s signal as it sped towards the Moon.

Only for it to fall silent at 21:01 UST as it crashed into the Marsh of Decay at 10,000 km/hr, just as planned.

Jodrell Bank’s director, Bernard Lovell, almost missed the event.

Underestimating its significance, Lovell had been at a local cricket match and only just about made it back in time.

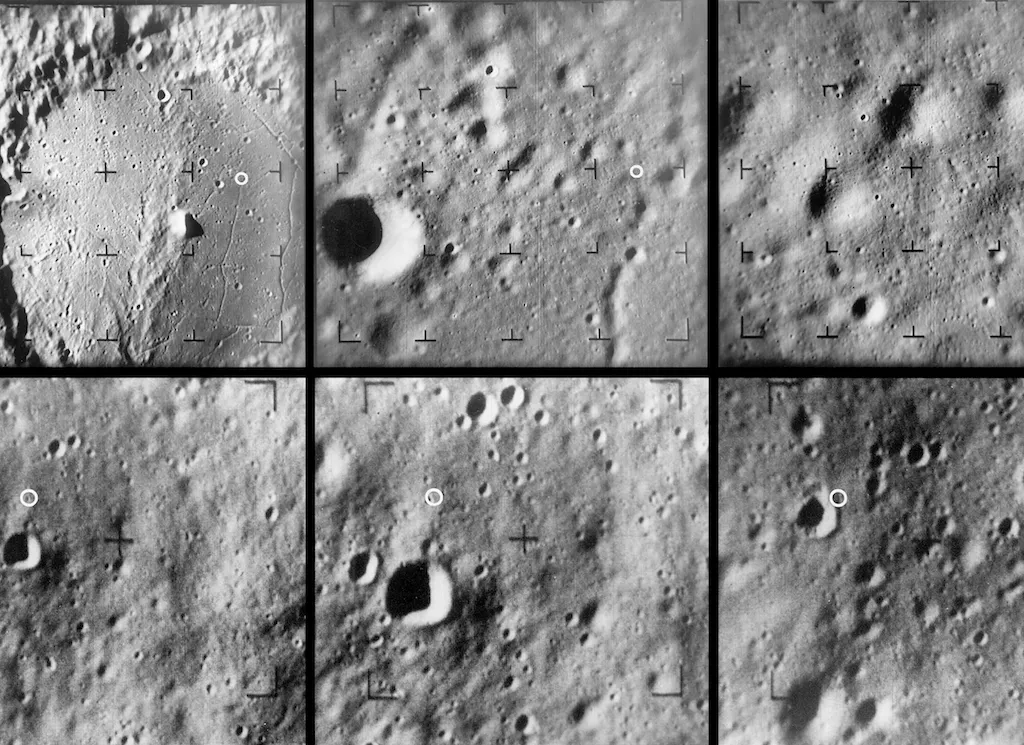

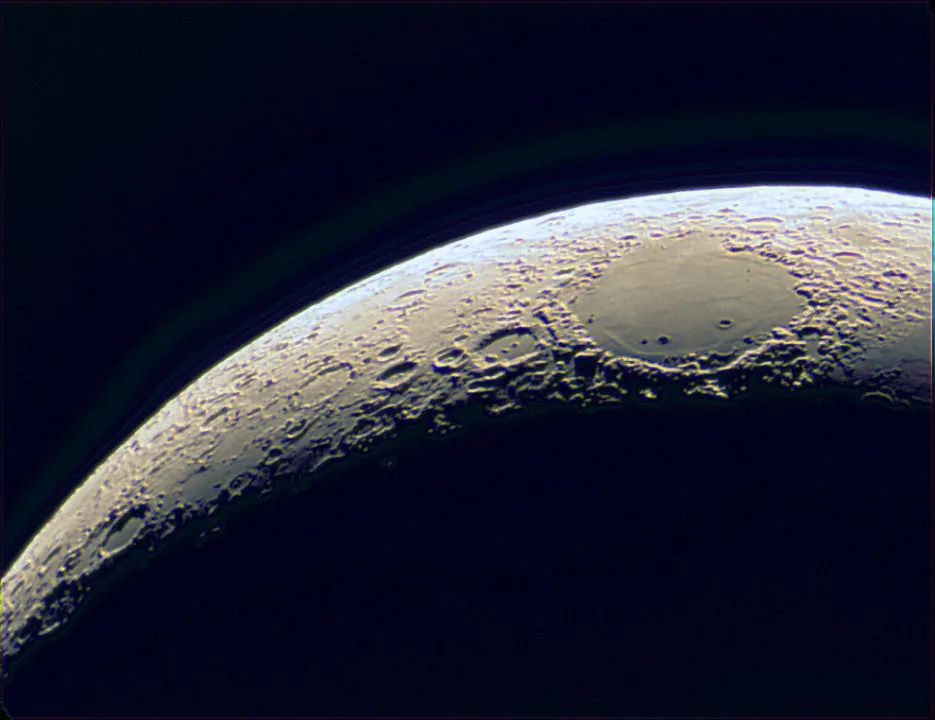

Less than a month later on 4 October, follow-up mission Luna 3 set course for the Moon.

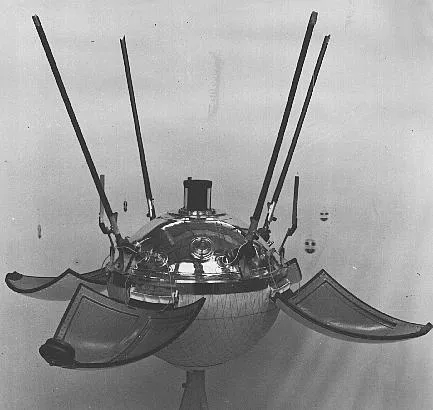

Luna 3 was an orbiter mission, which would send back the first ever images taken from lunar orbit.

With digital photography still to be invented, these were taken using a film camera.

The negatives were developed onboard, then transmitted back to Earth using the same technology television transmissions used.

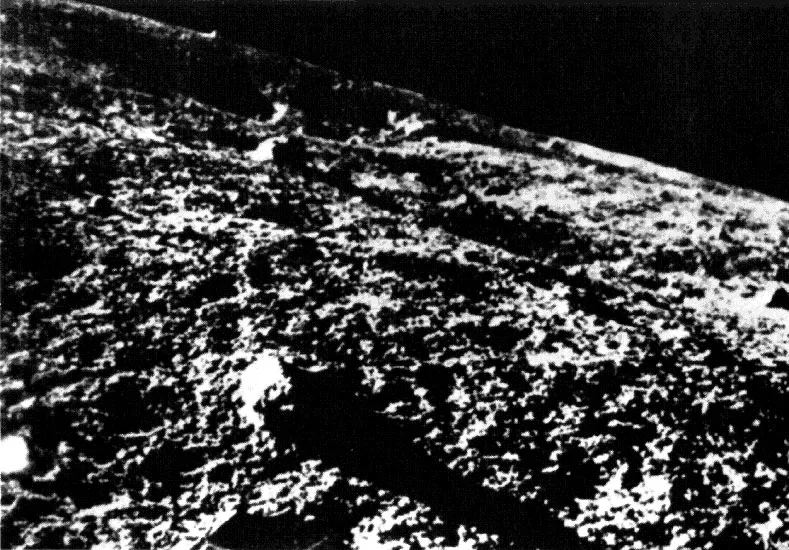

It took 29 images on 7 October of a place never seen before by human eyes – they were the first ever photographs of the far side of the Moon.

Soviet attempts to soft land on the Moon

By the end of 1959, the Soviets had achieved a whole raft of firsts – first flyby of the Moon, first to touch it, first photography of the far side.

Meanwhile the US ‘s much publicised first launch attempt, Vanguard-1, had made it just one meter off the ground before crashing, resulting in a global embarrassment.

However, NASA was having far more success with the Explorer programme and were now attempting to reach the Moon with the Ranger lunar impactors.

If the Soviets wanted to maintain the lead in the Space Race, they needed another coup, and the first controlled soft landing on the Moon was an excellent prospect.

Unfortunately, the task would prove difficult, and both the US Ranger and Soviet Luna programmes experienced a run of failures over the next few years.

Soviet naming convention meant any mission that failed never received a Luna title: many of the first attempts failed to even reach this milestone.

One mission did manage to earn the Luna 4 title in April 1963 by making it to orbit, but got no further.

Luna 5 wouldn’t earn its name until May 1965. This time, the spacecraft not only left Earth orbit but actually made it all the way to the lunar surface.

Unfortunately its retrorockets failed to fire, meaning it did so at a rather terminal velocity.

In June the same year, Luna 6 had the opposite problem when its thrusters wouldn’t turn off, causing it to miss the Moon by 160,000km.

The lander did still execute its manoeuvre perfectly, albeit several hundred thousand kilometres off target.

October’s Luna 7 experienced an astronavigation failure and crashed.

Things were looking better in December for Luna 8, which made it to the Moon in once piece.

It was on course, making its final descent and everything going well. All it needed to do was deploy the airbag that would cushion the landing…

Something snagged. The airbag punctured, sending the spacecraft spinning, causing it to crash.

The Soviet Union’s new leader, Leonid Brezhnev, was increasingly unhappy with a string of failures and gave the Soviet Luna programme one last chance before he cancelled the whole thing.

On 31 January 1966, Luna 9 made its way into the sky.

It made it to Earth orbit.

It made its manoeuvre to send it towards the Moon.

Its retrorockets fired and its air bag deployed without puncturing.

The 99kg lander jettisoned just before the main spacecraft crashed into the surface, temporarily cutting off contact with Earth.

For four nail-biting minutes there was silence, but then Luna 9 started to transmit back.

The Soviets had landed on the Moon.

The US begins to win the Space Race

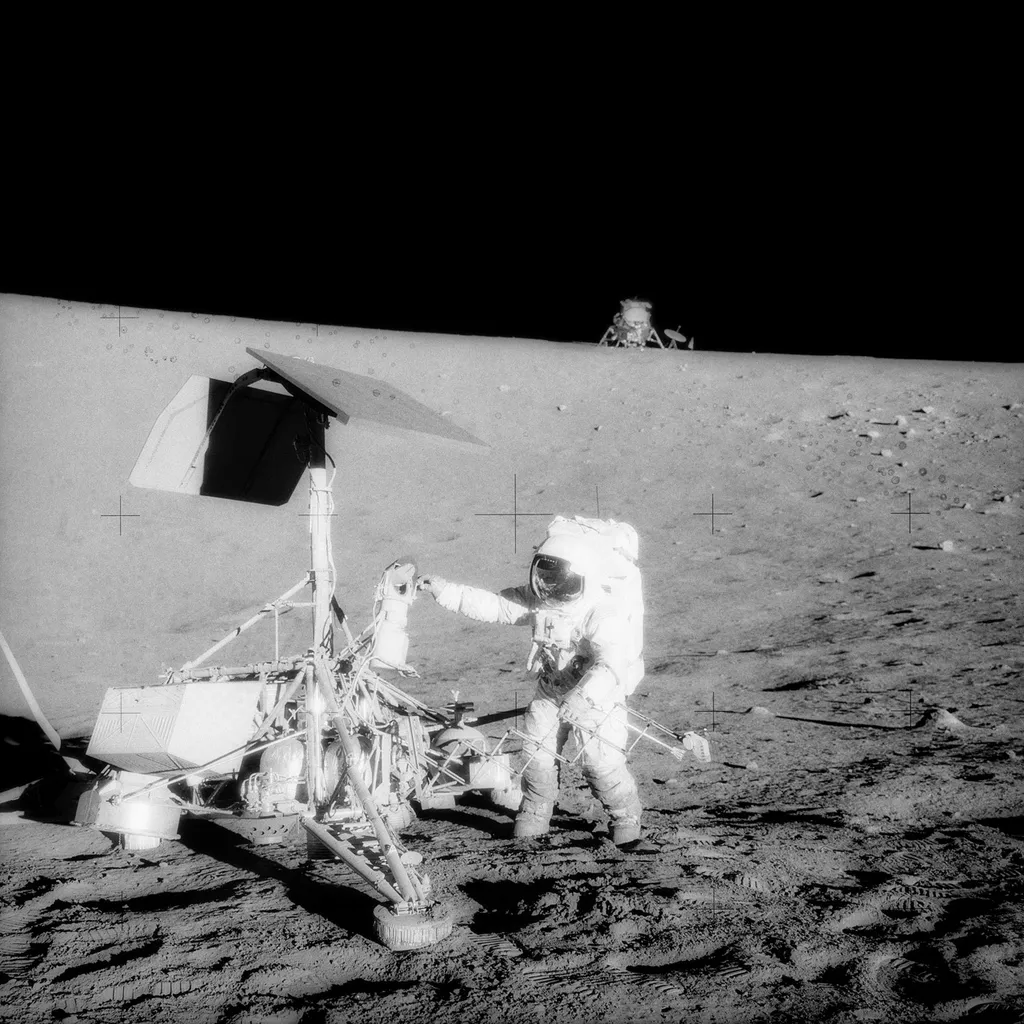

The Soviets might have landed first but the US were close behind.

Their first soft lander, Surveyor 1, touched down on the lunar surface a few months later on 2 June 1966.

Since JFK had announced “we choose to go to the Moon” in 1962, NASA was throwing everything they had at the lunar programme.

Luna 9 had been a simple craft with only a rudimentary camera and a radiation detector.

Surveyor 1 had an advanced wide-angle camera with a zoom lens, and the capability to host far more complex instruments to examine the lunar surface on future iterations.

The Soviets had got their first, but it was clear the US had got there in style.

The next three missions – Luna 10, Luna 11 and Luna 12 – were orbiters, examining the Moon’s composition and structure from above, for as long as their batteries allowed.

But when time came for Luna 13 to touch down on the Moon’s surface on 24 December 1966, its simplistic science instruments – including a penetrometer to investigate the soil – looked rudimentary against their American counterparts.

Though they didn’t publicly admit it, the Soviets were attempting their own human lunar landing.

But it was quite clear they could never hope to match the astronomical budget the US had assigned to its Apollo mission.

In the Space Race, the US was simply outspending them.

The Soviet Luna programme could never hope to land a human on the Moon before the US, but perhaps they didn’t have to.

What if rather than landing a human on the Moon, they instead proved they could do everything the US was doing at a fraction of the cost and without risking human lives?

After another orbiter mission with Luna 14 in April 1968, the Soviets set the stage for what could have completely changed the narrative of the Space Race – from ‘US vs Soviet’ to ‘man vs machine’.

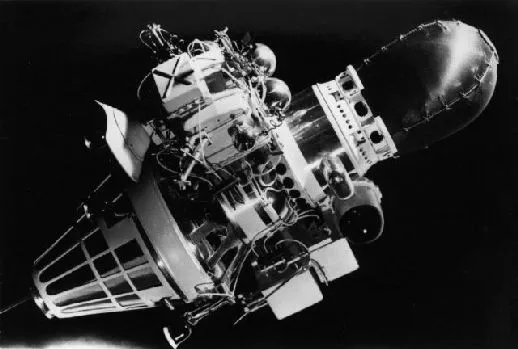

On 13 July 1969, three days before the launch of Apollo 11, Luna 15 set off for the Moon.

Initially, the Soviets refused to say what the mission was for, leading to rumours ranging from it being a potential rescue mission to a spy satellite that would prove whether the landing actually happened.

Or even a sabotage mission to ensure it didn’t.

In truth, it was a robotic sample return mission to collect samples of the lunar soil, known as regolith, and return them to Earth before the Apollo astronauts.

The landing was initially set for 19 July, just as Apollo 11 entered orbit, but issues with Luna 15’s landing radar delayed the landing by 18 hours.

This meant the astronauts would beat them home, but Luna 15 would still show up Apollo 11 as an expensive extravagance… if it could just return the samples.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t to be.

As Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin prepared to leave the lunar surface, Luna 15 struck the aptly named Sea of Crises (Mare Crisium) at 480km/h.

Soviet sample return missions to the Moon

Though Luna 15 had failed to change the narrative as hoped, the Soviet Luna programme continued with Luna 16.

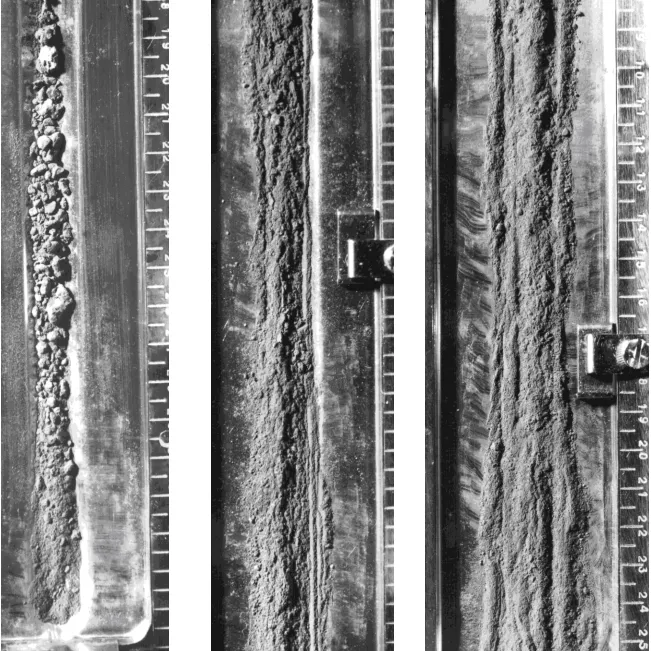

This time the mission met with considerably more success, and it touched down in Mare Fecundaitatis (Sea of Fertility) on 20 September 1970.

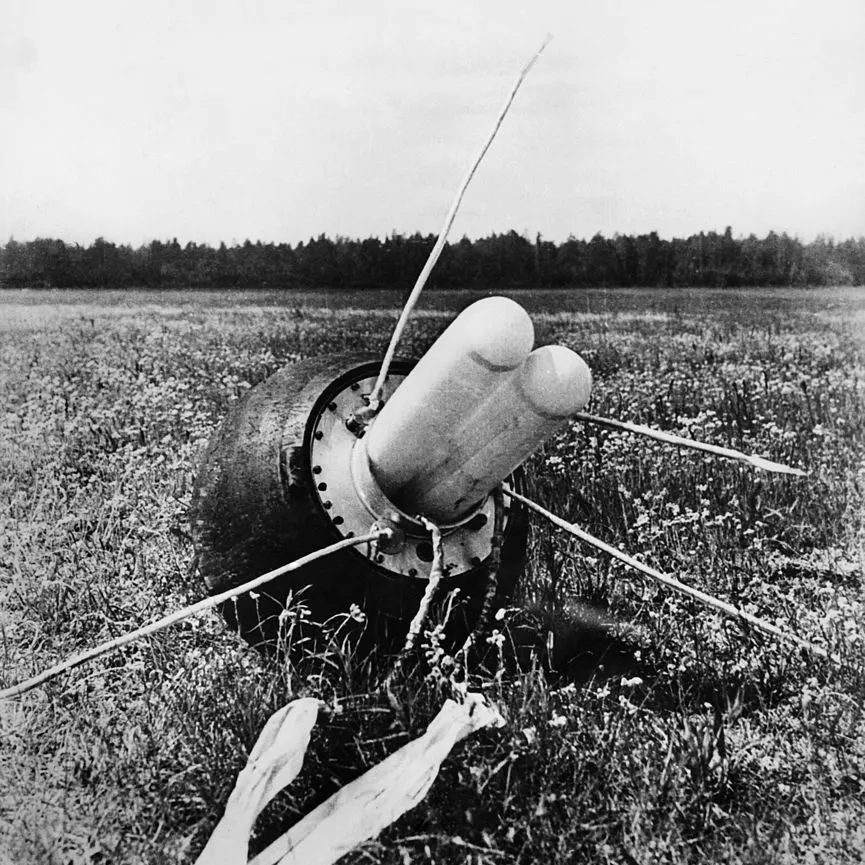

Four days later, it returned to Earth carrying 101g of regolith.

A tiny sample compared to the hundreds of kilograms brought back by Apollo, but at a fraction of the cost.

Luna 18 crashed while attempting to collect more samples in September 1971, meaning the second successful sample return mission, Luna 20, landed on 14 February 1972, returning 50g from a mountainous area known as the Apollonius highlands.

The sample was almost lost when a storm blew it off course into a river, but fortunately it landed safely on an island in the middle of the stream.

Luna 23 was unable to take its sample in October 1974 after being damaged during landing.

Fortunately, Luna 24 was able to prevent the Soviet Luna programme from ending on a sour note.

It landed on the Moon on 18 August 1976 in the exact spot Luna 15 was meant to land and recovered 170g of lunar regolith.

The Soviet lunar rovers, Lunokhod

Between these sample returns, the Soviet Luna programme made several other launches.

Luna 19 and 22 were another set of orbiters, but it was the remaining pair of missions that were arguably the most impressive of the entire programme.

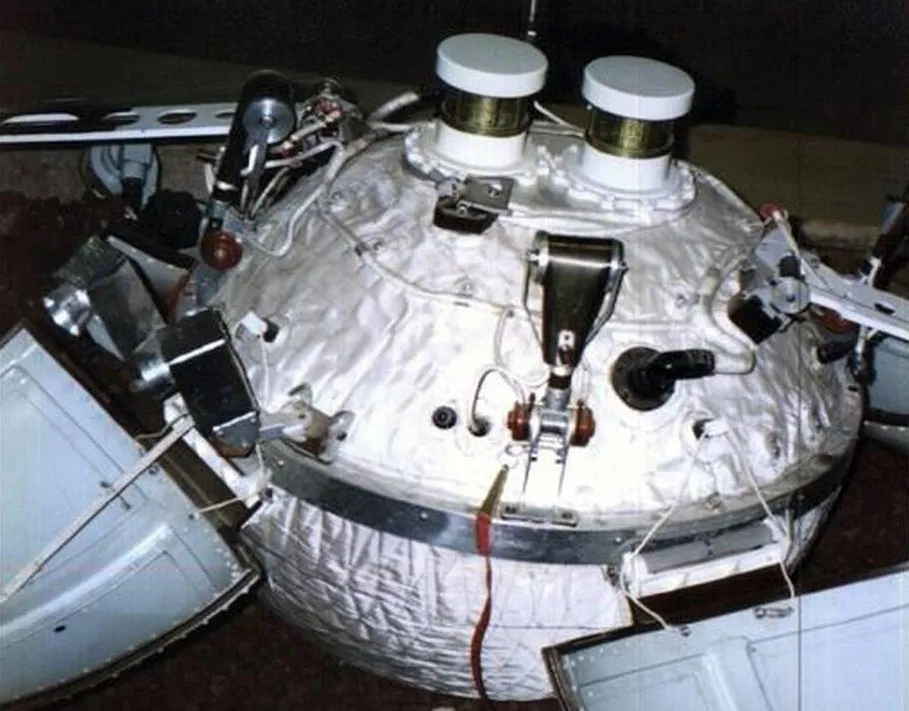

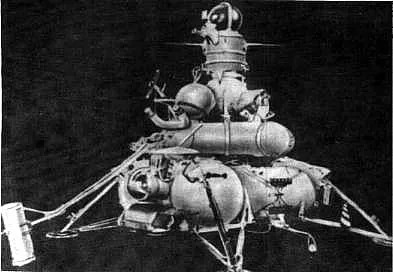

On 17 November 1970, Luna 17 touched down in Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) and the first Soviet ‘moonwalker’ took its first foray onto the lunar surface.

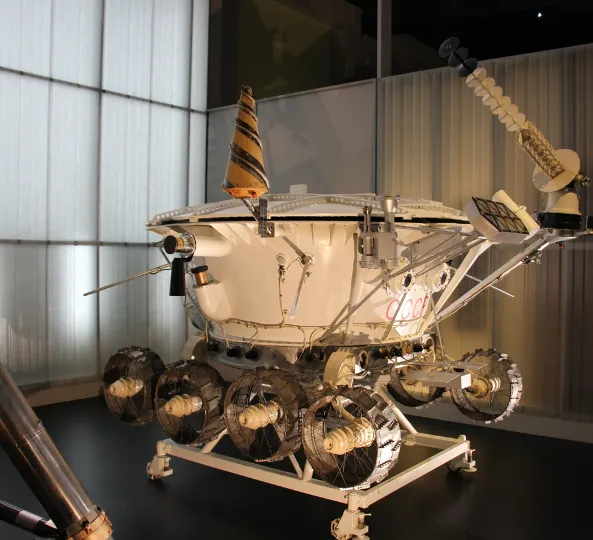

This wasn’t a human walker, but a robotic rover called Lunokhod-1 (which literally translates to Moonwalker-1) that had originally been designed to facilitate human landings.

Operated from Earth in real time, the 1.5m tall rover was powered by solar panels and equipped with a spectrometer and devices to probe the lunar soil, allowing it to examine the lunar surface in situ.

It operated for 11 lunar days exploring the surface, making its last contact on 14 September 1971, having travelled 10.5km.

Luna 21 arrived on the surface on 15 January 1973, carrying with it Lunokhod 2, which featured newly upgraded cameras, magnetometers and photometers.

Though it operated for just four lunar days, Lunokhod 2 travelled 42km across the Moon.

An astonishing planetary distance record that remained unbeaten until 2014, when it was overtaken by NASA's Opportunity rover.

You can find out more about the Lunokhod rovers and their role in our exploration of the Solar System in our on-demand online talk.

The legacy of the Soviet Luna programme

After Luna 24, the Soviet Luna programme was put on hiatus as the Soviets turned their attention towards Venus and their hugely successful Venera missions, as well as their Mars exploration program (which was distinctly less successful).

While the Luna programme is much celebrated in Russia today, they are often overshadowed by the Apollo missions in the West.

Though initially the Soviets kept most of their findings to themselves, in the decades since the Space Race much of the data gathered from the Luna missions has been shared with the international community.

Readings from the Lunokhod rovers are being used to inform how much weight the lunar surface can support ahead of the Artemis missions.

While the samples returned from the surface have been analysed at labs around the world.

On 10 August 2023, Luna 25 launched from the Vostochny Cosmodrome bound for the Moon, where it was due to touch down on 21 August.

However, Luna 25 crashed into the surface of the Moon on 20 August 2023.