Would you like to get into astronomy and explore the night sky, but don't know where to start?

Stargazing and observing the night sky may seem daunting, but by following a few simple steps you'll be amazed at the stars, constellations and planets that are visible, provided you know when and where to look.

Maybe you’ve just been struck by the view on a particularly clear night, or perhaps you’re someone who loves to read and learn about astronomy but have never got round to spending time outside studying the stars.

These 10 lessons will teach you what you need to know get into astronomy and start finding your way around the night sky.

For more, read our guide to 10 common astronomy mistakes - and how to avoid them, how to choose your first telescope and how to observe the Moon

Be prepared

All you need to begin stargazing is your eyes, but you should still plan ahead.

The most important thing you can do is get to the darkest place you can find where large swathes of sky are visible.

There are some bright objects in the sky at night – the Moon, the planets, a few dozen stars – but the dimmer things greatly outnumber them, and light pollution washes these out.

It takes your eyes up to 40 minutes to completely adjust to the darkness, so avoid looking at bright lights and, if it can’t be helped, consider wearing sunglasses before you start observing.

Wear comfortable, layered clothing outside: you can get colder than you might think when you sit or lie down for long periods of time.

Observe with family or friends, as this makes the whole exercise much more enjoyable.

Finally, take something comfortable to sit on outside and a flask of a hot drink.

Get your bearings

When you first get into astronomy, the night sky can be confusing. Random points of light appear on a dark background, and over a few hours these points will have changed position.

The sky seems different because Earth is rotating, but the patterns made by the stars stay the same relative to each other.

This means that if you know just one shape in the sky, you can find the rest.

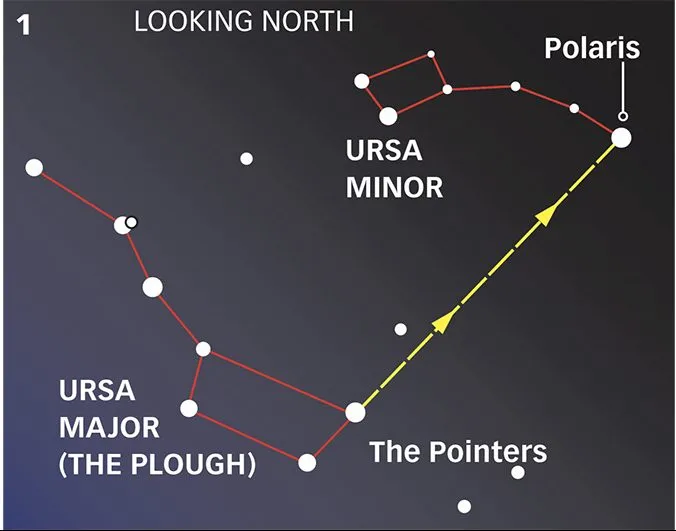

The best one to use as a guide is the Plough, since it is large, bright and visible year-round in the north: it's what's known as a circumpolar constellation.

It also has two stars called the Pointers - Merak and Dubhe - that point to Polaris, the North Star.

Polaris is positioned almost exactly above the Earth’s axis at the North Pole, so unlike the rest of the sky it doesn’t move and shows which way is north.

The Plough is also a useful pointer to other shapes in the sky.

Once you get a bit more experienced and begin using a telescope, there are deep-sky objects in the Plough well worth seeking out.

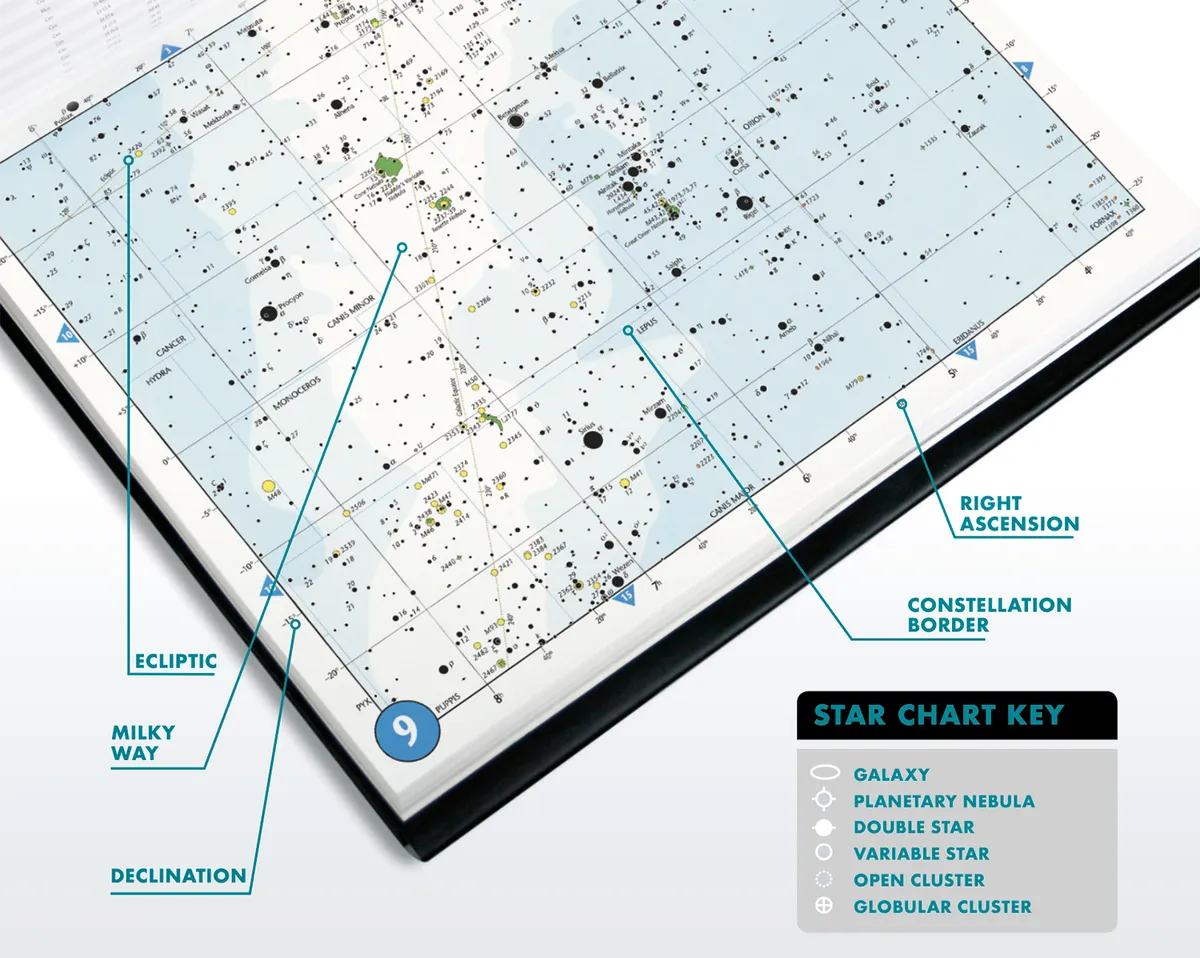

Use a star chart or app

A star chart is essentially a map of the sky that you can use to locate stars, constellations and deep-sky objects.

However, a star chart is unlikely to show you the location of the planets, because the planets don't always appear at the same position in the night sky at the same time every year, the way the stars do.

There's a monthly star chart available in each issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine, and you can find out how to subscribe to our print or digital edition at the top of this page.

A star chart may look confusing at first. Why is it ‘backwards’, with west on the right and east on the left?

Unlike most maps, a star chart one shows what’s above your head, not beneath your feet.

Hold it above your head with ‘north’ pointing north and you’ll find that east and west are in the right place after all.

To use it to look at things in different directions, hold it so that the bottom edge corresponds to the compass direction you are facing.

It will then show the sky as it looks from that horizon and on up over your head.

Once you find north, the rest will follow.

It’s best to use a red-light torch to see the chart in the dark – that way it won’t ruin your night vision.

Other tools that can help you navigate the night sky as you get into astronomy include stargazing apps and planispheres.

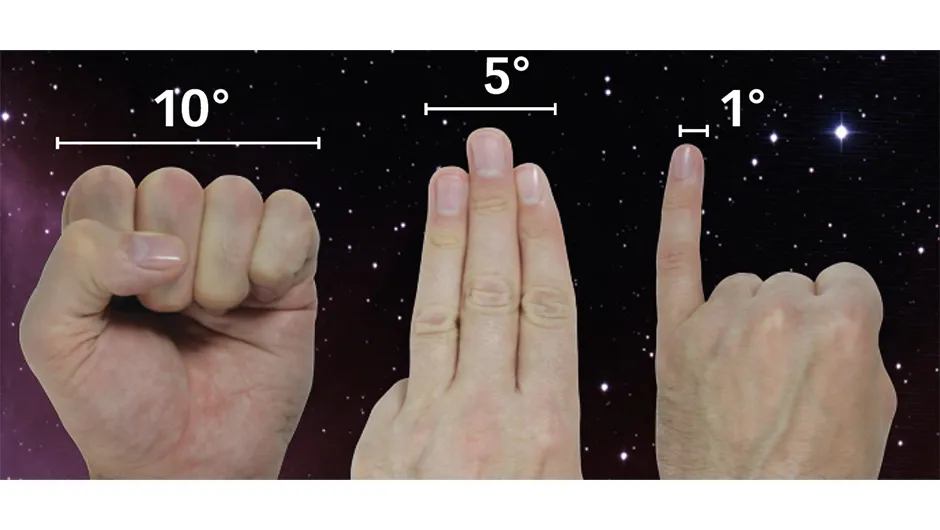

Use your hands to judge distances

Distances between objects in the night sky are measured in angles using degrees of arc, a bit like the angles of latitude and longitude on the Earth’s globe.

One degree is equal to 1/360th of a circle.

Conveniently, your fist held at arm’s length covers about 10º of the sky; three fingers are about 5º; and your little finger covers 1º.

If you want to find a dim object in the sky and a star chart shows that it is about 15º in a certain direction from a brighter, known star, then you can use your outstretched hand as a ruler to measure off the distance on the night sky.

Between the two Pointer stars of the Plough, for example, the distance is about 5º.

Watch the sky move

When you get into astronomy, you will notice that the night sky changes in appearance over time.

Stars keep the same positions relative to one another, but seem to move as a whole.

Earth spins on its axis once every 24 hours, so the globe of the sky revolves 15º to the west every hour.

Earth orbits the Sun in about 365 days, so stars are in slightly different positions at the same time each night.

Stand in one spot at 9pm and watch a star rising above a rooftop to the east, then look again at 10pm and the star will be 15º higher.

Fourteen days later, it would be close to that position at 9pm, as the sky will seem to have moved 1º west each night.

Observing this change will give you a good sense of the motion of our planet and how it affects our view of the heavens.

Navigate the sky by starhopping

A great way to get into astronomy is to start simple and progress towards more difficult targets.

The simplest things to find are the patterns formed by groups of bright stars.

The entire sky is divided into 88 of these patterns, called constellations.

Some of them are quite bright, and many of their striking patterns and names have been with us for thousands of years.

Once you can find your way to some of the brighter constellations, locating the dimmer ones becomes easier too.

It also makes finding even dimmer objects – like galaxies and star clusters – easy too, using the technique of starhopping.

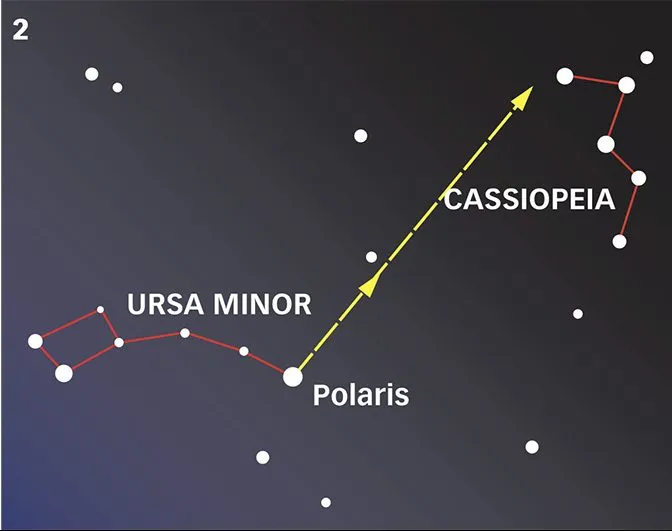

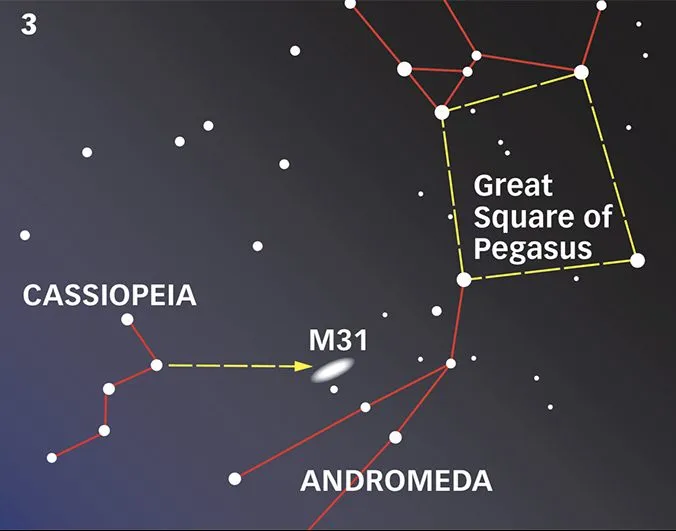

Use the three charts below and hop from constellation to constellation to find the Andromeda Galaxy, also known as M31.

Under very dark skies, it’s possible to see M31 with just your eyes, even though it is dim and difficult to pick out if you don’t know just where it is.

To find it, start at the Plough (above).

Use the Pointers to find Polaris, and then keep going past it to the constellation of Cassiopeia (below).

It’s an easy shape to see because its brightest stars form a ‘W’.

Once there, you can use the less flattened triangle of the ‘W’ as an arrow: its apex points towards M31, about 15º away (below).

Use your newfound skills to pin-point this beauty.

Want more? try these 4 star hops to help you navigate the night sky.

Magnify the sky

The starhop above was meant for naked-eye viewing, which is possible for M31 because it’s visible under very dark skies.

But locating it through the light pollution above towns and cities, or finding even dimmer objects requires a good pair of binoculars or a telescope.

Binoculars give you some magnification, but more importantly they greatly brighten the view.

With good vision under ideal conditions, you might be able to see a couple of thousand stars with just your eyes, but using a good pair of binoculars you’ll see over 100,000.

There are two numbers used to describe most binoculars: 10x25, 7x35, 7x50 and 10x50 are all common combinations.

The first number describes the magnification, or the number of times larger an object will appear.

The second number is the aperture – the diameter in millimetres of the lens at the front of the binoculars.

This determines how bright the image will be.

A small increase in aperture can make a big difference in brightness.

Images seen through 7x50 binoculars will be twice as bright as those seen through a pair of 7x35s.

If you divide the aperture by the magnification, you get the exit pupil – the diameter of the circle of light that enters your eyes from the binoculars.

The pupils of your eyes can expand to 7mm when they’re adapted to the dark, so a pair of 10x50 with a 5mm exit pupil are ideal for most people.

Explore the night sky with your binoculars

If you’ve not used binoculars very often, they take some getting used to.

Practice by looking at the Moon first. Look at the Moon, then lift the binoculars to your eyes and focus while looking through them.

To help hold them steady, give them added support other than your arms.

When standing, rest your thumbs on your cheek bones, and when sitting or reclining, much of the weight of the binoculars can be rested against your face.

For the steadiest views, you can buy L-shaped brackets that will attach any good pair of binoculars to a camera tripod.

This lets you see the most detail, and you can share the stable view with others.

Through binoculars, you’ll get an even better view of the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, which you first found in lesson 6.

Experiment with different optics

With your eyes alone, you can see plenty of interesting objects in the night sky. But binoculars open up the Universe.

With time and practice, you’ll see the planets as discs of light, asteroids, the subtle colours of stars, nebulae, galaxies like M31 and much more.

Still, there are limits.

While binoculars improve on the view by allowing you to see dimmer things, they also narrow the view.

If you want to see the constellations in their entirety, look at them with the naked eye.

But though binoculars bring things closer, they don’t magnify enough to show detail on any of the planets.

While giving amazing views of the whole Moon, they won’t show fine detail, like crater walls or snaking valleys.

Larger telescopes are needed for these.

Even telescopes will not show some things: even through the largest scopes, the stars still appear as points of light, because they’re so far away.

Get outside and look up

Your eyes and a pair of binoculars are enough to keep you busy for a lifetime.

With just your eyes, you can see meteors and meteor showers, aurora (Northern Lights), an occasional bright comet, whole constellations, and the sky-crossing Milky Way – our own Galaxy.

With binoculars you’ll be able to see much more.

Craters and ‘seas’ are visible on the Moon, and beyond the Solar System, you’ll see double and multiple stars, globular clusters and nebulae and galaxies.

You should also get in touch with your local astronomy society and see if they are hosting a star party or stargazing session that you can attend.

Find out more with our guide to UK and Ireland amateur astronomy societies and UK and Ireland star parties.