Not all stars are constant in brightness, with many appearing to vary in output over time. Observing variable stars is a fulfilling and immensely important part of amateur astronomy, especially if you have the opportunity to do it regularly.

Long-term observations reveal just how they change with time and give vital information about the nature of the variability.

However, it’s not just stars that vary in brightness, as some nebulae do it too and we’ve picked three for you to track down and observe.

Variable nebulae are reflection nebulae that appear to change in brightness due to changes in the star that is illuminating them, or that star’s environment.

There are three primary examples of variable nebulae visible in the Northern Hemisphere:

- McNeil’s Nebula

- Hind’s Variable Nebula, NGC 1555

- Hubble’s Variable Nebula, NGC 2261

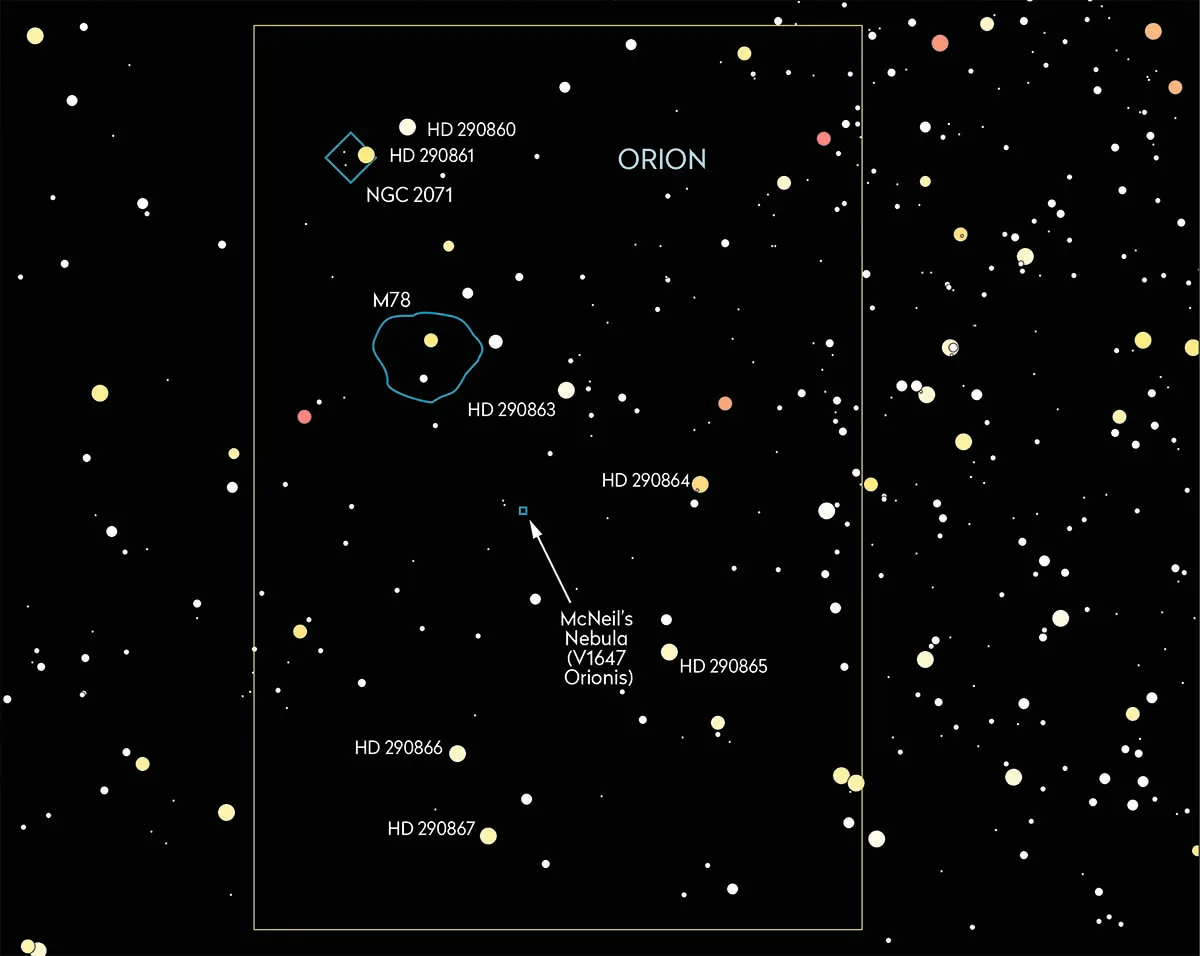

McNeil’s Nebula

McNeil’s Nebula, located in the constellation of Orion, the Hunter is a fairly recent discovery, having been identified as variable back in January 2004 when it was discovered by Kentucky-based amateur astronomer Jay McNeil from his back garden.

It’s associated with the variable star V1647 Orionis and is located 16 arcminutes south-southwest of the refection nebula M78.

Around 15th magnitude, McNeil’s Nebula is best suited for observation with large instruments or deep-sky imaging setups.

Interestingly, back in 2018 the nebula disappeared completely and observing its reappearance (if this eventually occurs) is especially important.

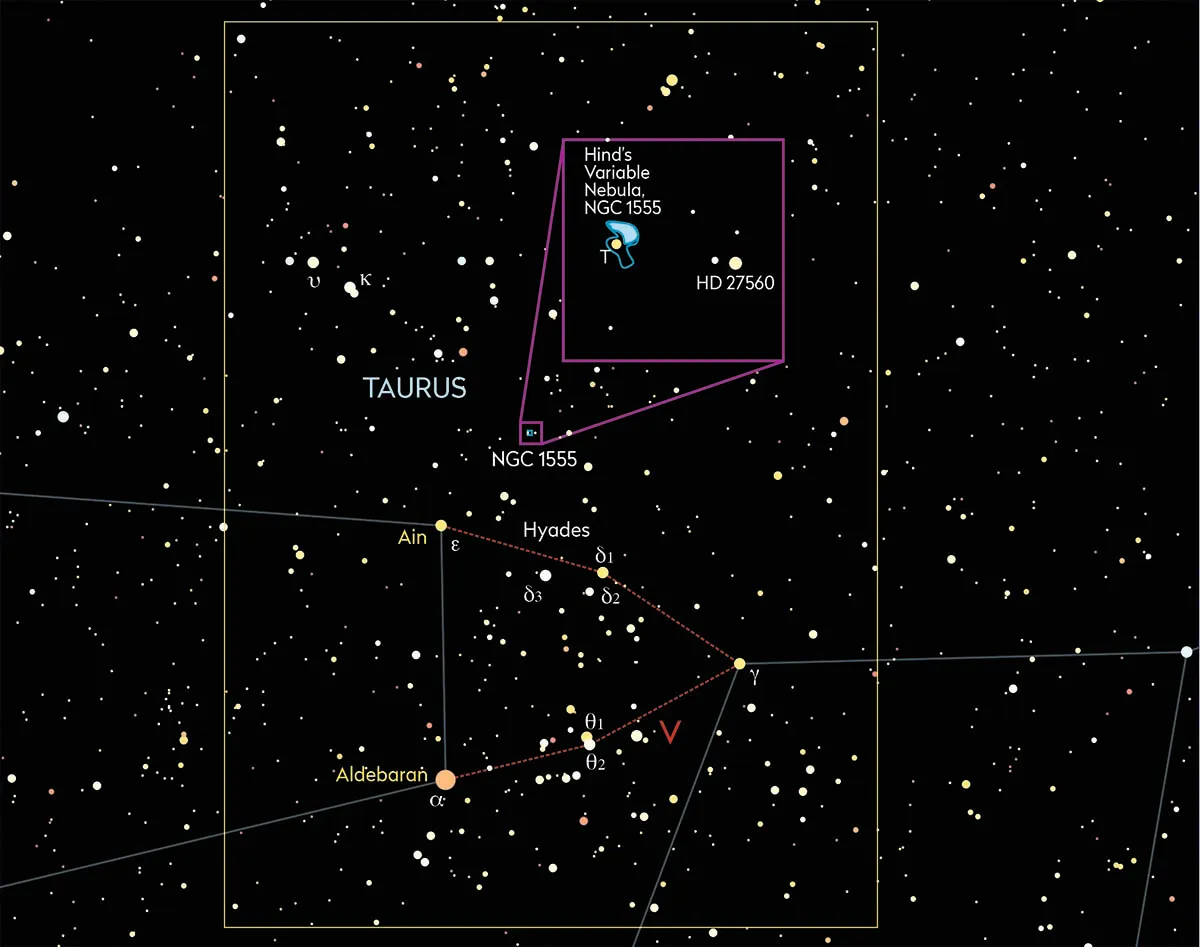

Hind’s Variable Nebula

Hind’s Variable Nebula, NGC 1555, is located in the constellation of Taurus, the Bull and it was discovered in 1852 by English astronomer John Russell Hind.

It is associated with the young variable star T Tauri. The star appears close to the Hyades open star cluster, M25, but in reality is more distant.

It’s an easier object than McNeil’s Nebula with an average magnitude of +9.6. Visually it appears as a faint arc near T Tauri and this is where the challenge comes in, because the star’s glare makes it difficult to see.

T Tauri is estimated to be around one million years old and varies in brightness between mag. +8.5 and mag. +13.5.

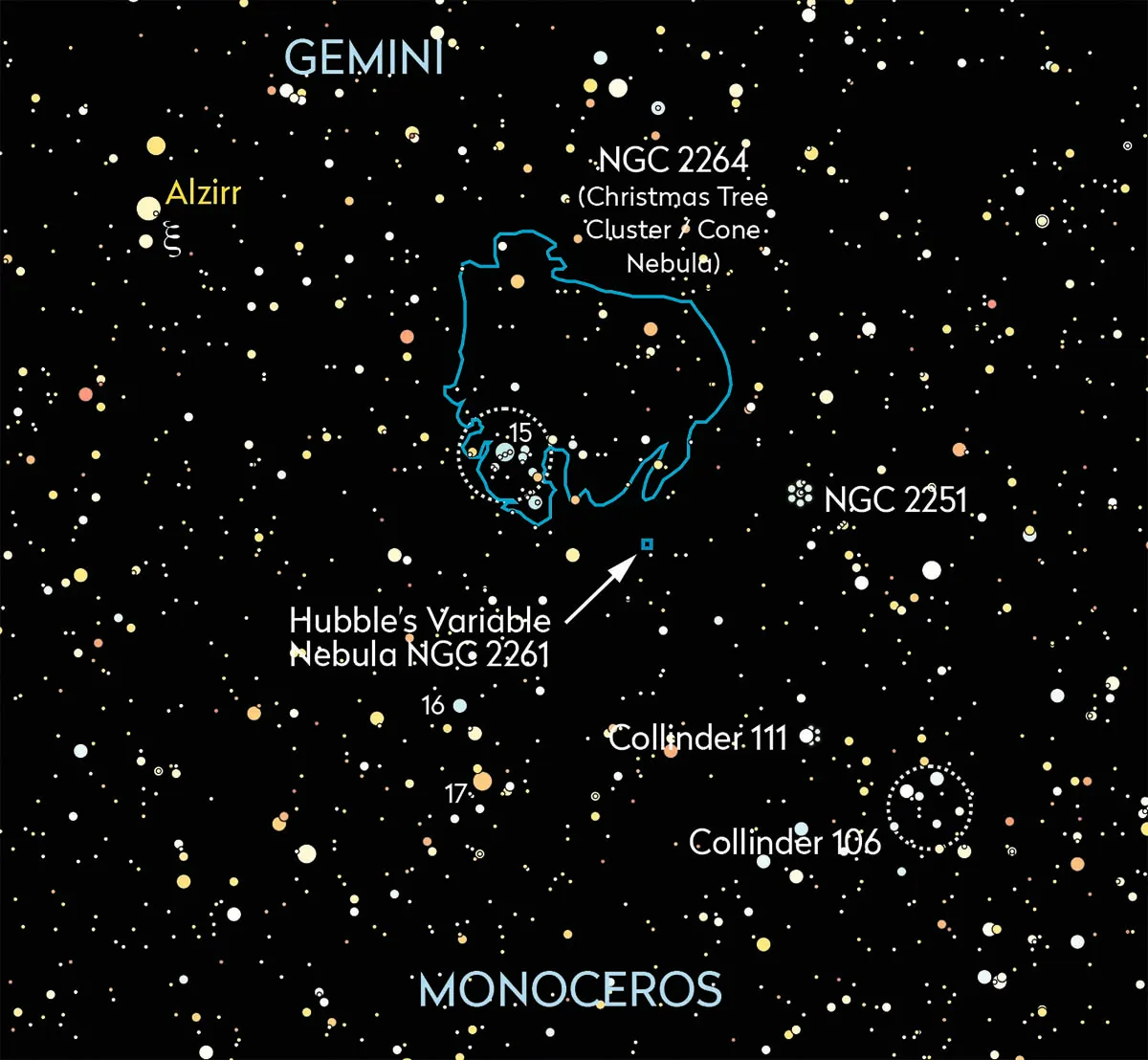

Hubble’s Variable Nebula

Hubble’s Variable Nebula, NGC 2261, is a triangular-shaped region of nebulosity in the constellation of Monoceros, the Unicorn, illuminated by R Monocerotis.

It was discovered by the US astronomer Edwin Hubble in 1949. With an average brightness around ninth magnitude, this is a fascinating object.

Its variability is believed to arise when dense clouds of dust near R Monocerotis create shadows that pass across the nebula. The nebula appears around 2 arcminutes across.

Astrophotography is a good way to create an observational library of these objects. For help doing this, read our guide to deep-sky astrophotography.

If you take images of each one over the course of many months – and eventually years – you will find that animating the results will reveal how amazing these objects are and how their appearances alter.

In the case of the disappearing McNeil’s Nebula, the process of determining how long it takes for the nebula to reappear is especially important.

All three objects are well placed around December time, so why not add them to your regular observing run? Your observations may help decode exactly what makes these nebulae tick.

Find out more about variable nebulae via the British Astronomical Association's Variable Nebulae webpage, and don't forget you can always submit any data you collect to them and make a contribution to citizen science.

This guide originally appeared in the December 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.